By: Michael Roberts

The Last Day, August 28, Lulie St, 10am More than four hours before the first game at the newly named Jock McHale Stadium, and the last at Victoria Park, trains unloaded swarms of football fans wearing black and white jumpers, jackets, scarves and a few long-neglected duffle coats. The masses congregated on the platform and headed towards the ground, over the railway yard and into crowded Lulie St. Sausages sizzled on barbecues, face painters daubed long lines of children in layers of black and white war paint and people waited patiently for admittance through the old turnstiles. One poor soul clutched a large cardboard sign, held in desperation and blind hope, with a plea that read: “I will do anything for a ticket.”

Many of the fans circled the ground one last time, taking it all in, walking down Lulie St to Turner St, then into Bath St and around the corner from Trenerry Crescent into Abbott St. A precious few parking positions were reserved in Turner St for those willing to fork out a little extra. One person in an old Holden evaded a security net and illegally parked his car in one of the spots. His mate jumped out and said: “You can’t park there, you’ll get a fine or be towed away.” The Holden driver smiled. A parking fine would be considered a souvenir on a day like this.

Some kids were flying for speccies on the little grassy area on the corner of Turner and Bath Sts. Families and friends, fathers with their sons on their shoulders, mates and strangers gathered and entered the ground to watch a game there one last time, talking about the old days and how footy used to be when it was simply a game, not an industry.

The Last Lunch, 11am The game was still hours away when Eddie McGuire turned on the biggest president’s lunch in footy – 1200 people in all. A collection of past players, the board, sponsors, officials, the media and some fanatical fans with $350 to spare listened to Eddie’s last Vic Park lunch. He told the audience that this would be a day that no one would forget. First, he handed out a history lesson, saying: “In the 1800s Collingwood, the suburb, was on the bottom rung of the socio-economic scale. It was the flatlands of Melbourne, the dumping ground to the abattoirs and shoe factories.” Then he rewrote history when he welcomed Melbourne’s Lord Mayor as “the Mayor of South Collingwood.”

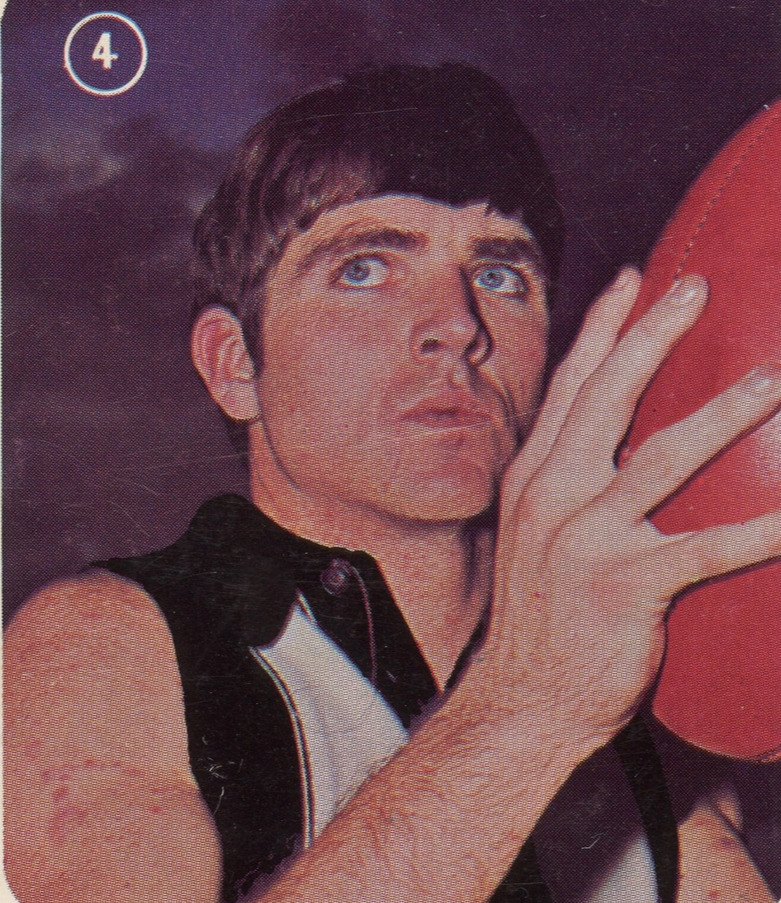

The former players in attendance signed everything from footy records to serviettes, from menus to footballs. Peter McKenna, McGuire’s hero as a kid, was one of the most sought after, just as he was when he wore No.6 in the goalsquare across the road. Even Jock McHale, son of the legendary coach who spent more than half his lifetime at the ground, and a former player himself, signed his share of autographs. When he signed a footy for a young fan, he paused to wonder what his father would have thought about leaving his “home away from home”.

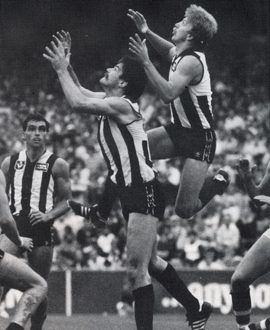

On The Ground, 1pm The old girl was decked out in her finest. The club’s 14 VFL Premiership flags fluttered in the chilly breeze from atop the Rush Stand, just above the names of the club’s most revered footballers. Temporary stands jutted out from the Yarra Falls end, a giant video screen started off slowly and without sound, before clicking into gear. A faint ray of sunshine failed to push its way through the ominous clouds.

A handful of past players strolled out onto the ground. One of them was not even a former Magpie. Ron Barassi was out there in a Melbourne jumper, shadowed in his every move by Barry ‘Hooker’ Harrison, of course. The former players were back on show to relive some of the club’s most famous or infamous deeds, most of which never happened at Victoria Park. But that didn’t really matter on a day such as this.

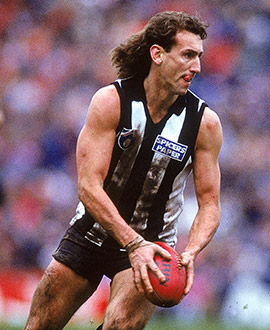

Denis Banks was standing on a stepladder out near centre half-forward. Banks was there to re-enact his mark of 1984 taken across town at the Western Oval. He re-emerged shortly after, looking as svelte as when he used to wear No.12, with a dummy wearing a blond wig. Banks belted the David Rhys-Jones effigy just as he had done to the real thing back in 1986. The dummy’s head fell off. Someone yelled: “Give him another one, Banksy.”

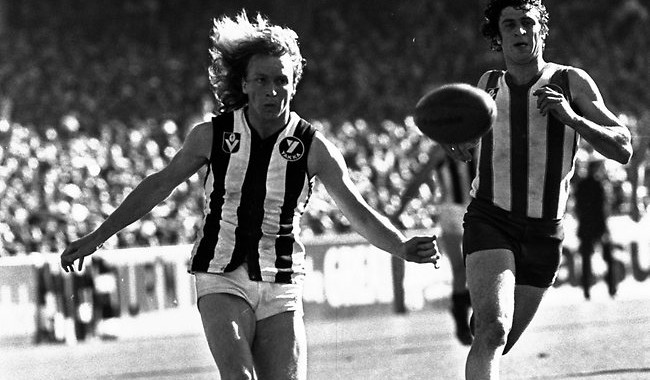

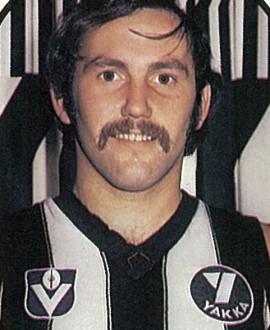

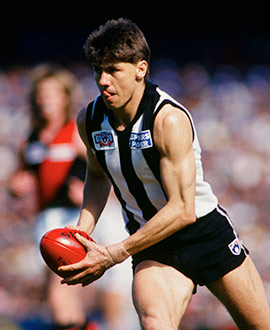

No one could accuse Phil Manassa of being svelte. He looked as if he had been in a fair paddock, and that’s precisely where he was on the Ryder Stand wing, with no one between him and the goals. He bounced once, clumsily at first, and then again, and again, with a little less pace and surety than he did along the MCG wing in the 1977 Grand Final Replay. The ball slipped off his boot and ended up in the Vic Park crowd. It was not the only piece of history to go awry. Ross ‘Twiggy’ Dunne missed his first attempt to recreate his famous goal from 1977, and even Peter Daicos’s magic from his trademark Social Club forward pocket took an extra shot before he nailed one in his inimitable style.

Then, there was the Dream Team – a chain of passes that linked Thommo and Tuddy and Pricey and Thorold and the Weed and the great Bobby Rose, Lou and Daics and …well, you get the idea. Fittingly, it finished with a McKenna goal. Fans began to dream, and to drool.

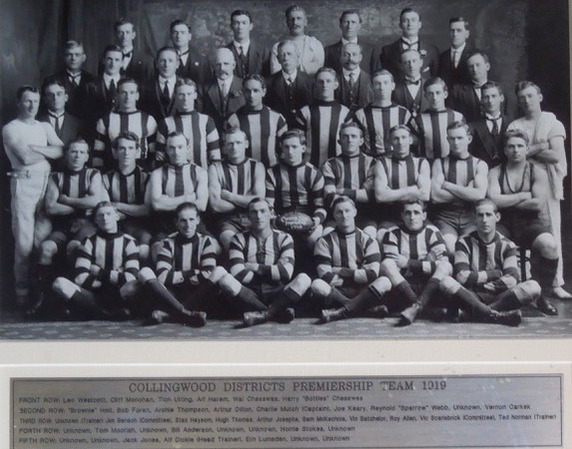

Then the serious tributes started. Legends circled the ground in golf carts in a few moving moments. The crowd roared in appreciation, cheering their heroes and remembering the good times, and a few bad ones. The biggest cheers were reserved for Bob Rose, Daics, McKenna, Tuddy, et al. One of those being driven around was less well known, but he enjoyed it every bit as much as the legends. At 98, Roy Allen was then Collingwood’s oldest living player. Never mind the fact he had played only two games, in 1924. He was a hero, too, on that last day at Victoria Park. Driven around the ground, Allen passed the spot where he used to watch games as a kid with his mate ‘Bottles’ Chesswas, when they used to sit next to timekeeper Jim Manning in the old Cowsheds in the years before the First World War.

The Last Pre-Match Speech, 1.45pm Tony Shaw’s words were muffled at first, lost somewhere in cyberspace. The giant television screen flickered and the audio crackled. Finally, the coach delivered his message to the 22 players, to the 26,000 in attendance and the hundreds of thousands watching around the country.

Shaw was saying goodbye. It was his last game as coach of Collingwood and the crowd was silent as he delivered his final instructions to his players. He gave one last plea for the team to play with passion. More than most, he knew what the history of the place meant to the fans.

He named some of the players who had carried the hopes of Collingwood. Great names, too – the Coventrys, the Colliers, the Richards, the Pannams, the Roses, the Twomeys, the Richardsons, to name but a few. Shaw told his team that Victoria Park used to intimidate opposition teams and players, and give those in the black and white strength. Shaw’s players did not especially know all the names, but knew the importance of the occasion. “Just go out there and know that there are 30,000 people out there who would love to be in your position today,” Shaw said calmly, but with purpose. “They would do anything to be in your position today.”

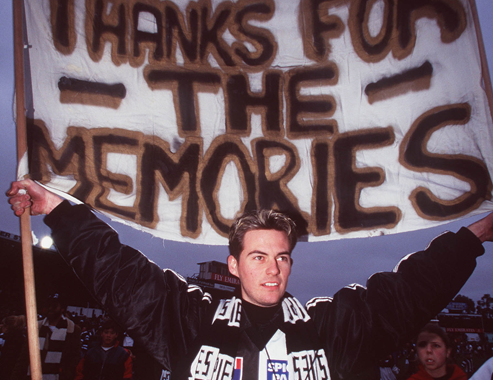

The Collingwood cheersquad were not listening to Shaw’s speech, however. They had their own mountains to climb, or to lift, to be precise. The farewell banner was a monolith of black and white proportions – a massive eight metres by 40 metres. They tried to raise it nervously as Shaw instructed his players. The Brisbane Lions cheersquad arrived to help them out. Finally, they managed to raise the banner just as the Collingwood players emerged from the race. The epitaph said it all: “Victoria Park 1892-1999, thanks for the memories.”

The Last Match, 2.10pm Pent-up emotion can be a double-edged sword. It can fire you up and make you achieve the extraordinary. Or it can cling to you and overwhelm you. Within a few minutes of the opening bounce that afternoon, the Magpies were overwhelmed. Emotion simply proved too much for the young Magpie players, or more to the point, the Lions proved too much for them. Brisbane kicked four goals in the opening six minutes and an eerie silence came over the venue that had roared for 108 seasons. Sadly, the final game was over in 15 minutes.

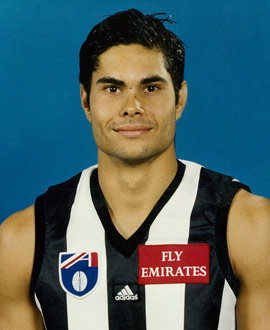

It took Collingwood 17 minutes to get the ball past the half-forward line. Finally, Anthony Rocca kicked Collingwood’s opening goal at the 20-minute mark. A cheer started up in the Sherrin Stand after Rocca’s goal and spread across the ground, ending the silence for a minute. The difference was 33 points at quarter-time; the game was shot. The Lions managed to shut down Collingwood’s attack and the home side faced the same deficit at the long interval, despite second quarter goals to veteran Gavin Brown and second year player Chris Tarrant.

The Interval and the Second Half, 3.30pm The first half was almost like a funeral, so perhaps it was appropriate that there was a wedding at half-time. Long-time fan Jennie Hallam’s longstanding joke with her fiancé Kevin Bear that they would become the first couple to marry at Magpieland came true in front of 26,000 fans and several hundred thousand gatecrashers. She tied the knot in the goalsquare of the Sherrin Stand to the bemusement of the crowd.

The knot tightened further for Collingwood in the second half. The Magpies failed to score in a dreadful third quarter; the old scoreboard was seemingly fixed on 3.3. The last quarter was at least a little better. Collingwood managed to outscore its opposition by five goals to three. But it was cold comfort. The final margin was 42 points, the Victoria Park scoreboard stuck forever on 8.4 (52) to 13.16 (94).

The Last Rites, 5pm Everyone was looking for Tony Shaw after the game. The players wanted him to be a part of the final farewell; they wanted to carry their coach off the ground one last time. But the man who made his name on this ground had gone off for a solitary Crown Lager. He had escaped the coaches’ box one last time and headed down the Ryder Stand steps, straight into the deserted Collingwood rooms. He wanted to be alone.

Out on the ground no one seemed to know what to do. Past players and the last 22 to represent the club on the ground lined up for Collingwood’s equivalent of the Last Post. The black and white flag was symbolically lowered. Nathan Buckley and Lou Richards, captains five decades apart, gathered to collect the flag. Bucks then handed it over to Eddie McGuire for safekeeping. “Good Old Collingwood Forever”, the song everyone wanted to hear, regardless of the result, was played over and over again. The legends on the ground seemed unwilling to leave, as if they did not want to say goodbye. Eventually, they shook hands, wiped away a few sentimental tears and left the ground.

For a few minutes the famous turf was empty, besides the army of police and security guards. Then a kid scaled the boundary at the Yarra Falls end. Like a leak in a dam wall, he was followed by more and more intent on having their personal chance at saying farewell. The ground announcer tried in vain to get them to leave, then simply gave up trying. Kids – and kids at heart – swamped the arena for one last kick.

Underneath the Ryder Stand, Nathan Buckley admitted the emotion had got the better of the players. Tony Shaw held his last press conference. Typically, he finished with a joke and said to the congregation of media that “we must have a beer, and it’s your shout.”

The After-Party, 6pm-late Queues for the “Vic Park Party of the Century”, the after-match function at the Walker Corporation building across Trenerry Crescent, started long before the final siren sounded the death knell for the ground. An hour after the game the queue stretched to 400m. When it was reduced to 200m, an official came out and said the party was sold out, just as the game had been. A few disappointed fans headed to the local pubs where fans congregated like they had for more than a century. In the “Vic Park Party of the Century”, the faithful toasted the old girl one last time, music blared from the speakers and the result of the 910th match involving Collingwood at Victoria Park was consigned to history.

The last Collingwood team to play at Victoria Park appeared on stage at 8pm. Finally, Tony Shaw emerged, too, to say goodbye after 21 years. He grabbed the microphone and said he could barely believe how a team that had finished on the bottom of the ladder, that had been thrashed earlier that day, could have so many loyal and dedicated supporters. Someone near the front chanted “Shawry, Shawry.” The crowd went into raptures when three players – Chris Tarrant, Mal Michael and Brad Fuller – belted out a rendition of the Village People’s YMCA.

The party concluded around midnight when the drinks ran out and the voices became hoarse. As the fans trudged off into the night, the raucous sounds of “Good Old Collingwood Forever” echoed along Abbott and Lulie Street. Finally, the curtain closed on the day we all said goodbye to Victoria Park, the day when football and the community welded together for one last, emotional time.

Postscripts There were two postscripts at Victoria Park, though they were never planned. Rather, they simply evolved out of two Collingwood Grand Final appearances, something that had seemed improbable back in 1999. When the Magpies made the 2002 and 2003 Premiership play-offs – against the Brisbane Lions, the team that had played in that last game at Victoria Park – fans turned out in their droves to watch the final Thursday night training sessions before the Grand Finals.

For a time, that atmosphere and special magic of the venue was switched on again. The fans were there in huge numbers – more than some games used to attract in the old days of suburban grounds – and they began streaming into the ground a couple of hours before training even started. The smell of sizzling sausages wafted over the ground. Many fans chose their vantage point those afternoons not based on where they’d get the best view to watch training, but on where they used to sit when the venue hosted league matches. Fathers and mothers brought their kids along to savour the moment, and thousands in attendance cheered every kick, mark and handball as if they had occurred in a match.

In 2002, particularly, there was an air of delightful unreality to it all. Only the most optimistic fan could have contemplated the idea of a Collingwood Grand Final appearance that year. Most were just happy to be there again, to know that the club was once more involved on the last Saturday in September. A year later it was different. There was genuine confidence about the result, a feeling that the Malthouse-led renaissance would be complete in just a few more days. They were memorable, happy afternoons; only the results in the games that followed soured the feelings.

At the end of those sessions, the players left the field for the sanctuary of the Ryder Stand change rooms to truly thunderous applause. Then that famous patch of turf belonged once more to the fans – many of whom took the opportunity to have one more kick-to-kick on the ground and think about the good old days of Vic Park.

Somehow this seemed like the kind of farewell Vic Park deserved. The team’s insipid performance ensured that the formal, structured farewell of 1999 had turned out to be a damp squib. But these were days to remember – a final celebration of Victoria Park, and all that it meant to the supporters of the Collingwood Football Club.