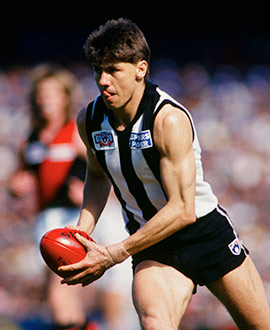

The 1979 season was a period of regeneration at the Collingwood Football Club: no fewer than 14 players debuted during that year. Among those debutants was a skinny kid from Preston called Peter Daicos, who would go on to become one of the all-time greats of the game.

But Daics didn’t win our Best First Year Player award that year. Instead, that honour went to his fellow northern suburbs recruit Denis Banks. That’s how highly Banksy was rated in the early stages of his senior career. And while he still ended up enjoying a marvellous career, Banks never quite made the impact he seemed destined to – almost entirely down to a horrendous run of injuries.

Born and raised in Reservoir, Banks played his junior football with a team called Thornbury Opportunity in the Preston and District Junior Football Association. Playing primarily as a ruck-rover, he won numerous club best and fairest awards and regularly polled well in the competition voting. As a northern suburbs’ boy, and with a father who had been born just around the corner from Victoria Park, it was virtually pre-ordained that Denis would follow the Magpies. Every Saturday, after playing with Thornbury in the morning, he would jump on a train to watch Collingwood in the afternoon.

Having finished with Thornbury in the under-16s he crossed to East Reservoir under-18s, and it was from there that he was recruited to Collingwood under-19s in 1978. He was called into the reserves late in the season, and in his first full game booted 10 goals. After just six games the next season he was in the seniors, named at centre half-forward against Geelong. He played 14 games that year, and showed plenty.

But from 1980 onwards it was one long battle against injury. He seriously injured his knee during the infamous 1980 night grand final (the one we lost only because the field umpire didn’t hear the siren), and that forced him out of the game for 12 months. After that he had repeated difficulties with his shoulders, severe and recurring groin complaints, major problems with his neck, a few broken bones and a host of related, niggling injuries such as hamstrings. In all he was forced out of close to 100 games in his 13-year career, and nevermanaged an uninterrupted season.

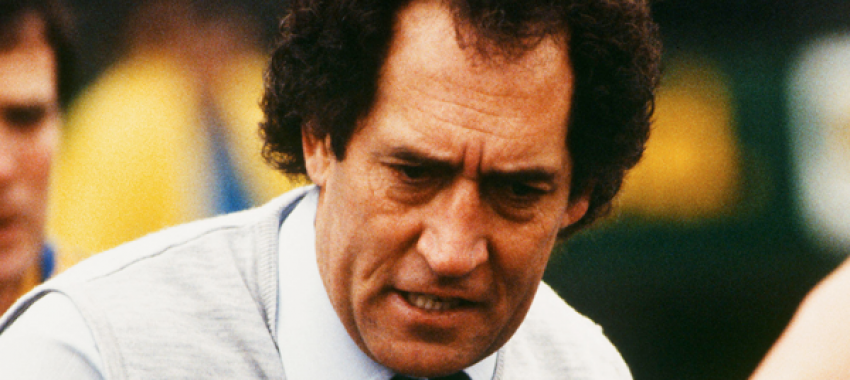

We saw the best of Banksy in 1984 and 1990. In the former year he played magnificent football at centre half-forward, despite really being too small for the position. He was a mobile target whose agility and athleticism made him difficult to mind, and whose marking against taller opponents had to be seen to be believed. At times that year he virtually carried the Collingwood attack, even down to performing a fair amount of the ruckwork in the forward line. He became one of the key players in a Collingwood team that was a little undermanned, and his performances that year earned him admiration all around — as well as the R.T. Rush Trophy for runner-up in the Copeland Trophy.

As well as becoming the team’s forward target, Banks also provided some badly needed aggression and toughness in attack. Although he looked slight on the field he had a wiry build that was deceptively strong, and in 1984 — as in most other years — he took some fearful knocks without flinching. For once virtually injury-free (he actually managed 18 games in a row), Banks’ confidence gradually returned, and he played the sort of free-flowing football of which he knew he had always been capable. His old spring even returned, and one particularly breathtaking grab against Footscray earned him the mark of the year.

Banks turned 25 during that year, and should have been into his peak years as a footballer. But just when it looked like the crowds might yet get to see him at his best, fate again intervened. He suffered groin problems throughout 1985, playing most of his 16 games under an injury cloud. Much of the good work of 1984 was lost.

The pattern continued over the next four years, injuries always restricting his appearances or limiting his effectiveness. It became a battle for him just to get on the field each Saturday, let alone worry about playing well. By 1990 his career looked to be over, with a neck injury that many thought would be the last straw. But Banks felt “something big” was about to happen at Collingwood, and he wanted to be a part of it.

So he tried physios, doctors and chiropractors and worked with a ballet teacher, just to keep his body flexible. The hard work enabled him to keep playing, and he was rewarded with his best form since 1984. Playing mostly at half-forward and occasionally in defence Banks had a wonderfully consistent season, displaying a kind of football that surprised those detractors who thought he was finished.

Then, in the fifth last round, he broke his wrist against St Kilda. The break was so bad that it probably should have meant an eight-week spell; Banks was back on the field in five. The work he put in was an inspiration to his teammates, who saw through his actions just what a Collingwood flag meant to him.

Inspiring teammates was something that came easily to Banks. The players had enormous respect for him, and coaches were keen to have him in the side. Part of the reason was that he was Collingwood through and through. His loyalty was as intense as it was unquestioned, and the players understood what he had gone through just to make it on to the field. He was part of the soul of the side. He was also a genuinely good bloke, easygoing and likeable, with a mischievous side that enjoyed practical jokes. It’s no surprise he became good mates with Darren Millane.

The other reason he was so valued by his colleagues was that he played a great team game. Banks did a lot of the little, hard things that players notice and appreciate but which often go unrecognised by the fans in the outer. He also brought a hard edge to the Collingwood game, not in a fist-swinging, wild type way but as a genuinely ‘hard’ man at the ball.

Carlton’s David Rhys-Jones told the magazine Footy Starsthat his worst moment in football was after he “accidentally clipped” Denis in a game at the MCG in 1986. Rhys-Jones said he knew retribution would be coming; he just was not sure when. He did not have to wait long. Only a few minutes later, Rhys-Jones dropped a routine mark. As he ran to pick up the loose ball Banks appeared from behind and swung a magnificent right hook that broke Rhys-Jones’ jaw. He was out before he hit the ground.

To make it even more dramatic Rhys-Jones had been heading straight towards a television camera at the time, and the punch was captured perfectly. Banks was, of course, suspended, but there were many football followers who felt it was worth it. To this day it remains one of the incidents for which Denis Banks is best remembered.

But far from the only thing. His colleagues recall a much-loved teammate – courageous and loyal and tough-as-nails. While for Magpie fans it’s the memories of the spectacular marks, the skills, the full-on attack on the footy and the crunching tackles that come first to mind. Always though, tinged with a little regret that one of the most injury-cursed players in Collingwood history never quite got the clear run at it his talents and commitment deserved.

- Michael Roberts

CFC Career Stats

| Season played | Games | Goals | Finals | Win % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979-1991 | 166 | 111 | 13 | 57.2% |

CFC Season by Season Stats

| Season | GP | GL | B | K | H | T | D | Guernsey No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Other CFC Games

| Team | League | Years Played | Games | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collingwood | Night/Pre-season | 1979 - 1989 | 11 | 5 |

| Collingwood | Reserves | 1978 - 1990 | 36 | 42 |

| Collingwood | U19s | 1978 | 15 | 32 |

Awards

x2

x2