By: Michael Roberts

The story of Victoria Park is longer than that of the famous football club with which it is so closely associated. Indeed, Victoria Park's history as a ‘place of public resort and recreation’ predates the Collingwood Football Club by some 14 years. And its 'pre-history' goes back even further.

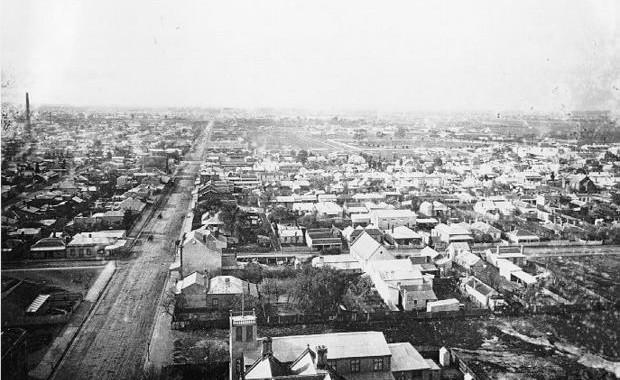

Victoria Park was first purchased by John Dight in 1838 for 13 pounds and 12 shillings an acre. Dight bought 84 acres bounded by Johnston St and Reilly St, between Hoddle St and the Yarra River, and bequeathed the family name to the land until the 1870s (hence its less than flattering original tag of Dight’s Paddock).

The land served many and varied purposes before the belated birth of the Collingwood Football Club more than 50 years later. The Paddock was covered with eucalyptus and casuarina trees and its few open glades provided the stage for frequent aboriginal corroborees. The Wurundjeri tribe inhabited the Paddock long before it was first sold by the white man. In 1838 there were said to be 124 members of the tribe in the district. But the urban growth which spread over Collingwood during the next 30 years, and the onset of new diseases, would have tragic implications for the tribe. Just 18 remained in the district in 1862. Those few remaining tribe members were ‘often to be seen around the area in their possum skin coats, armed with spears, and retreating mainly to the unsold hill north of Collingwood where they camped with their dogs, played football with a possum-skin ball and fought with other Aborigines’. Soon the Wurundjeri tribe would be gone from Collingwood forever.

Cattle also grazed on portions of the Paddock. Later, it would prove a popular destination for Sunday school picnics, as well as the location of the Collingwood Baby Show. For a time, the paddock was even used as a dumping ground. More fittingly, it was chosen as the venue for Collingwood's proclamation as a city in 1876.

The land was sold a year after that proclamation for almost 20 times its original purchase price. Its new owner, Edwin Trenerry, had no association with Collingwood or the increasingly popular pastime of Australian Rules. He lived almost 20,000km away in England.

The sale was orchestrated by solicitor David Abbott and clerk Frederick Trenerry Brown, the latter a nephew of the new owner. Trenerry's land would skyrocket in value almost immediately, thanks to some astute business nous from Abbott. Abbott made a proposal to the Collingwood Council for them to take possession of part of the land for use as a community recreation reserve. On face value, it was a noble gesture. However, the offer of 10-and-a-quarter acres carried a catch – the Council had to agree to spend 250 pounds per acre towards ‘the making of the streets around and leading to the reserve’. That sum was precisely the amount Trenerry had paid for the land and it was clear that any such work on making the road around the Paddock would dramatically raise the value of the land.

Several Councillors vehemently opposed such a fiscal commitment. But the majority ruled and a deal was struck between the Council and the owner in May 1878. For propriety's sake, the Council decided they would deem the new land acquisition as a ‘gift’ to stifle any possible rumblings of discontent from the community about wasted expenditure. This led directly to the popular folklore that Dight's Paddock was somehow donated to the Council for its use as a reserve. There was no such benevolence on the part of the owner. The suggestion it was a gift was clearly a distortion of the truth and a long way from reality, as documented in Richard Stremski's Kill for Collingwood.

But even though it wasn't a 'gift', and Abbott's motives were perhaps not as pure as first thought, an important step had been taken: part of Dight's Paddock was about to become a community recreation reserve.