Sometimes the thing that makes a footballer vulnerable becomes the very trait that endears him to the fans.

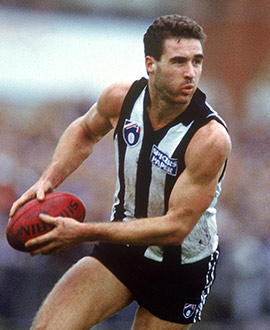

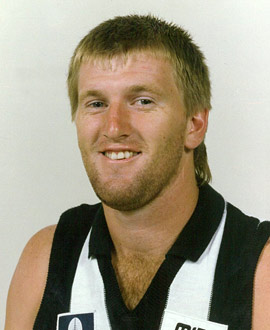

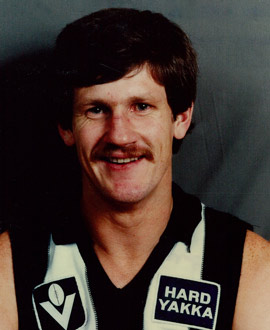

There are few better examples of this than the love Collingwood supporters have always reserved for James Manson - premiership player, hardworking ruckman/forward, inspirational teammate, and Collingwood cult hero of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

Part of that came from his laid-back personality off the field which sometimes seemed at odds with his passionate, aggressive attack on the ball on the ground. It may also have come from his capacity to work himself up before games, which sometimes included crashing into the lockers to fire himself up.

But undoubtedly much of the love came from Manson's awkward kicking style that more often than not had those in the crowd wincing, yet cheering doubly hard whenever he managed to slot through a goal.

Manson, by his own admission, wasn't a great kick. That may be one of football’s great understatements.

Asked late in his career what was the funniest thing he had seen on the field, he said with a smile: "Well, it usually involves me. I find it funny to hear people laughing when I kick for goal. Usually, people applaud players who score goals, but they always laugh at me because of the way I kick the ball. I actually don't think my kicking is that bad!

"Technique is something you can't really change. But you can get more effective."

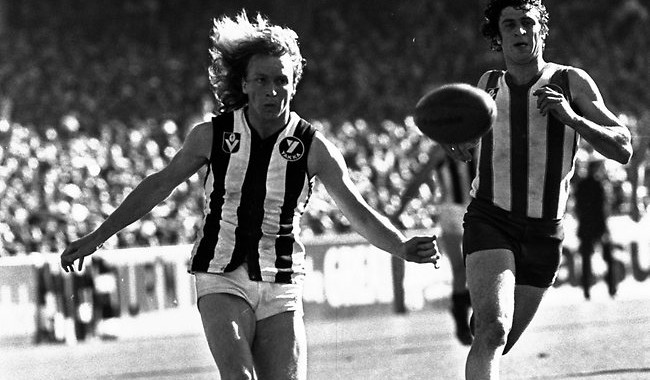

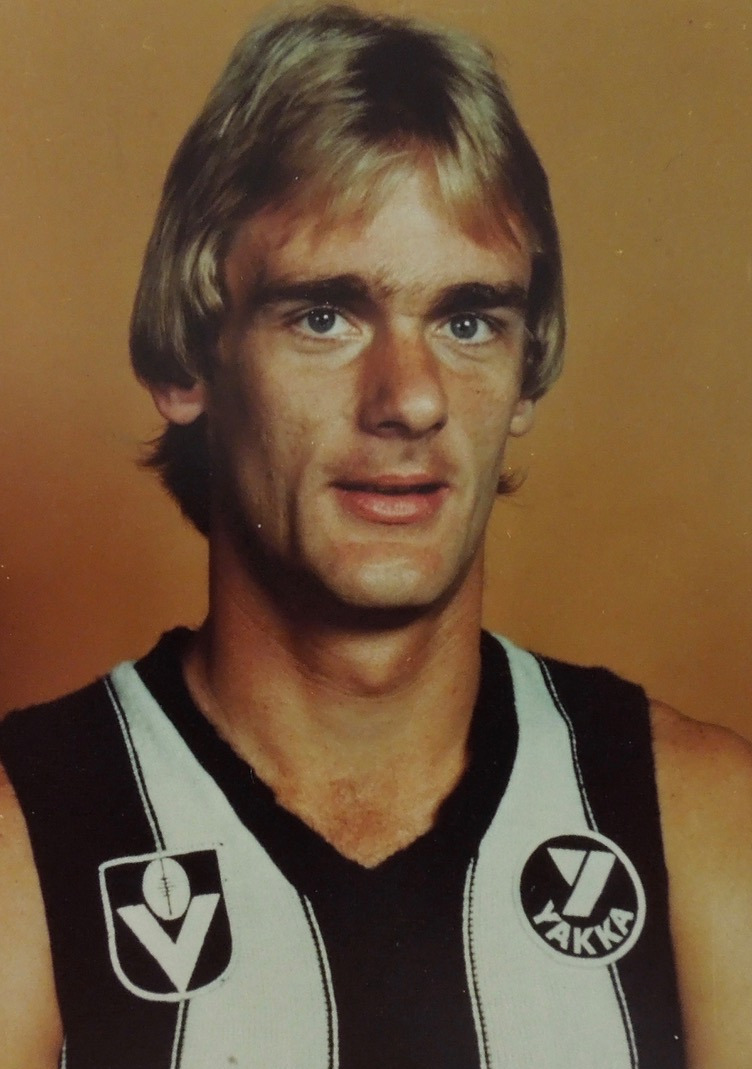

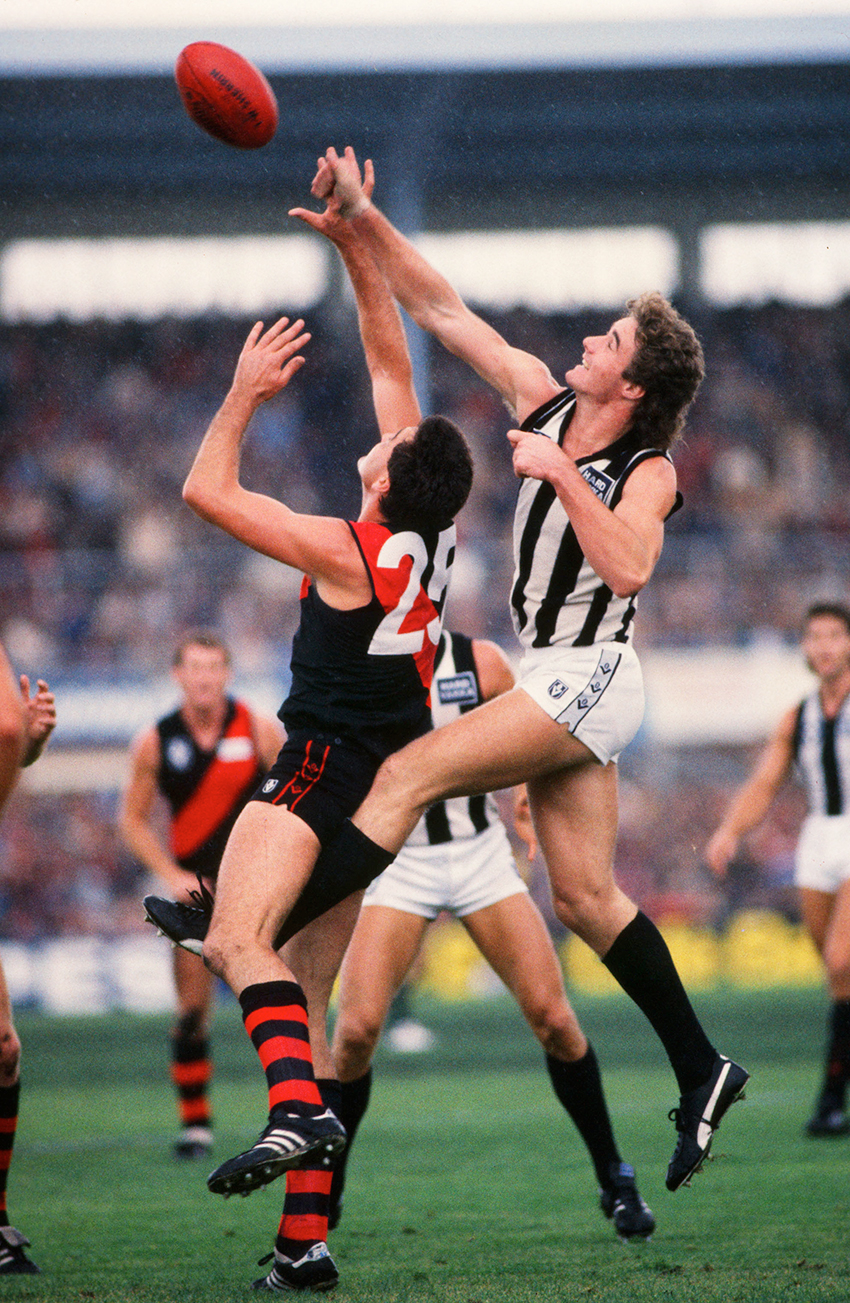

Punching from behind during his early days.

That he kicked 106 goals in his 120 games in black and white showed that maybe his technique looked worse than it was.

Famously, in a game against Geelong at Waverley in 1992, Manson grimaced in pain after taking a great mark 20m out near the boundary line. He was attended by two trainers and looked “down for the count” when teammate Ron McKeown was granted the shot instead by the umpire.

McKeown’s goal brought about Magpie cheers, but there were jeers from opposition fans as Manson sprang up, offered up a beaming grin and sprinted back to the middle for the next ruck hit-out.

After the game, he said: “I’ve had some back trouble, and (the physio) might have thought I’d aggravated it.

“I was trying to get my breath back. The umpire asked me if I could take the kick and I asked him to give me a couple of seconds to recover.

“But Ronnie grabbed the ball and took kick. I’m spewing about it. I would have loved the chance to kick the goal. I would have backed myself to kick it.”

Ever the showman, Manson stuck to his story, even if most people didn’t buy it.

But whatever anyone ever said about his kicking, no one could ever question his importance to the Collingwood Football Club at time when the club was desperately chasing that elusive 14th VFL-AFL premiership, nor the pain he went through to achieve the ultimate in football.

He became an important part of the jigsaw puzzle the club was piecing together through the mid-to-late 1980s, and he played a role in what unfolded on a memorable October afternoon in 1990.

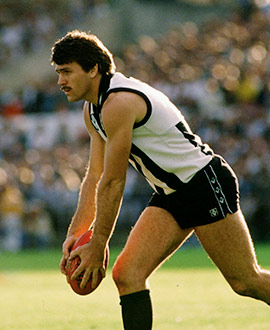

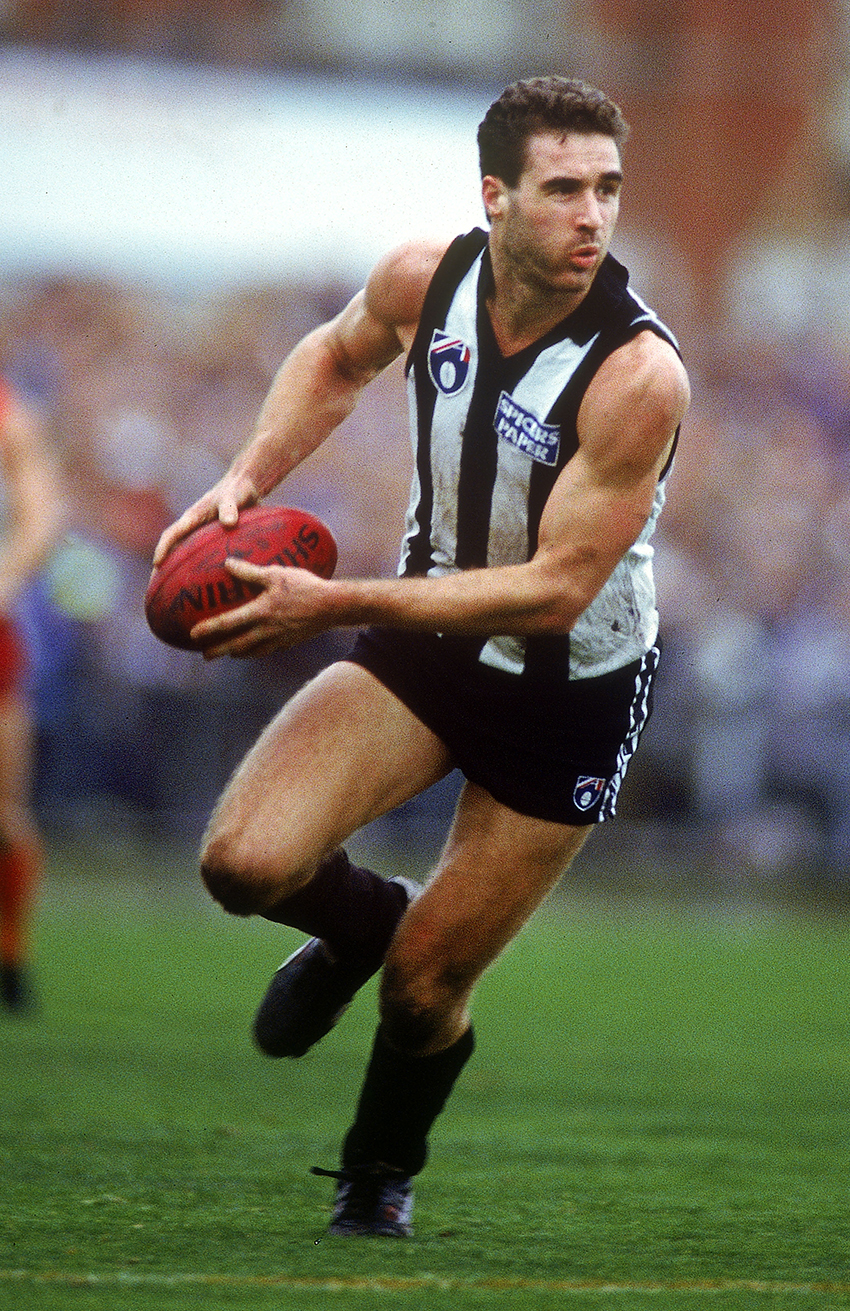

On the charge along the Victoria Park flank.

That seemed fitting as Manson had grown up with a stout Tasmanian football pedigree, while always bleeding Black and White. The son of 'Gentleman Jim' Manson, a star footballer with Glenorchy, James loved his footy. But much of his focus was on his favourite club, Collingwood, across Bass Strait.

One of Manson's earliest memories was waking one morning in 1977 and heading to the shops as early as they opened to buy Black and White balloons to decorate the family house. It was Grand Final day, 1977, and the 10-year-old watched on television as Collingwood drew with North Melbourne before losing the replay the following week.

As a young footballer, he came under notice of the Magpies, and was recruited to play in the Under 19s and the reserves, where he made an immediate impression due to his willingness to work and his desperation.

It was a dream-come-true for the Magpie fan, who once said he would "go and stand in the players' room for hours and look at the photos and talk to the old players."

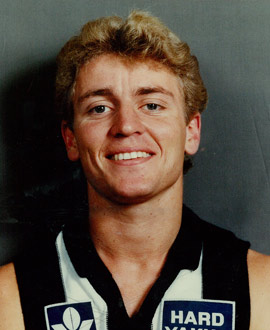

Wearing the No.30 jumper that his hero Peter Moore had worn only a few years earlier, Manson graduated to the seniors along with fellow debutants Russell Dickson and Tony Burgess in the round one, 1985 clash with North Melbourne at the MCG. It was a historic match of sorts - the first Friday night game played at the MCG.

Brian Taylor kicked seven goals that night; Manson managed one behind and nine possessions.

He would kick five goals - 5.0, at that - in only his seventh game on a day in which Collingwood kicked only eight for the game, and Hawthorn scored six.

"I was on the bench the next week, for the entire game, and the week after I was dropped," Manson recalled.

Still, he played 18 games in that debut season. But in the following two years he could manage only 10 games, due to chronic groin issues. He had several operations, to the point where Tony Shaw once said "Jimmy has got more lines on his groin than in a Melways."

He re-established himself in the Collingwood team in 1988, and although he stood only 194cm, he became the club's first choice ruckman for a period, keeping other big men out of the side.

One of the biggest compliments came from his coach Leigh Matthews who said Manson "plays the way I like ruckman to play". He even said Manson reminded him a bit of a young Don Scott.

Manson never worried about his size when going up against the huge ruckmen: "I've got a pretty good leap. I think I can beat most ruckmen." He also had a strong mark for someone of his size, and a scan of YouTube today still provides a good example of this.

He played 17 games in 1988 and a further 18 the following year. All of this led to Manson's most productive season, in 1990, which included a strong performance for Tasmania in their win over a Victorian B side.

He called that Tassie victory "a dream come true ... that probably rates as the biggest game I've played in."

Manson had to reassess that statement a few months later as Collingwood charged on towards the 1990 finals series. He didn't miss a game in that season, kicked 33 goals for the season, and shared the ruck position with a young Damian Monkhorst.

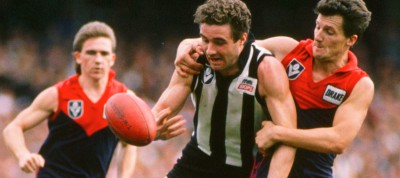

He was critical in the drawn Qualifying Final against West Coast, thumping the ball forward on many occasions.

For the first part of the finals, he was the No.1 man in that role. But Matthews went with Monkhorst in the first ruck against Simon Madden in the Grand Final, although Manson assisted him ably throughout the game.

His captain, Tony Shaw, recalled: "No other bloke his size attacks the ball better.

"He has no inhibitions about what he wants to do to the opposition side and the boys get into him about his 'I want to kill them comment'. He always yells it out.

"In the premiership season, he showed a lot of controlled aggression, running at the ball. I say to him every game: 'If you run hard at the ball, you hurt people'. He's that bloody boney and strong that he hurts buggers."

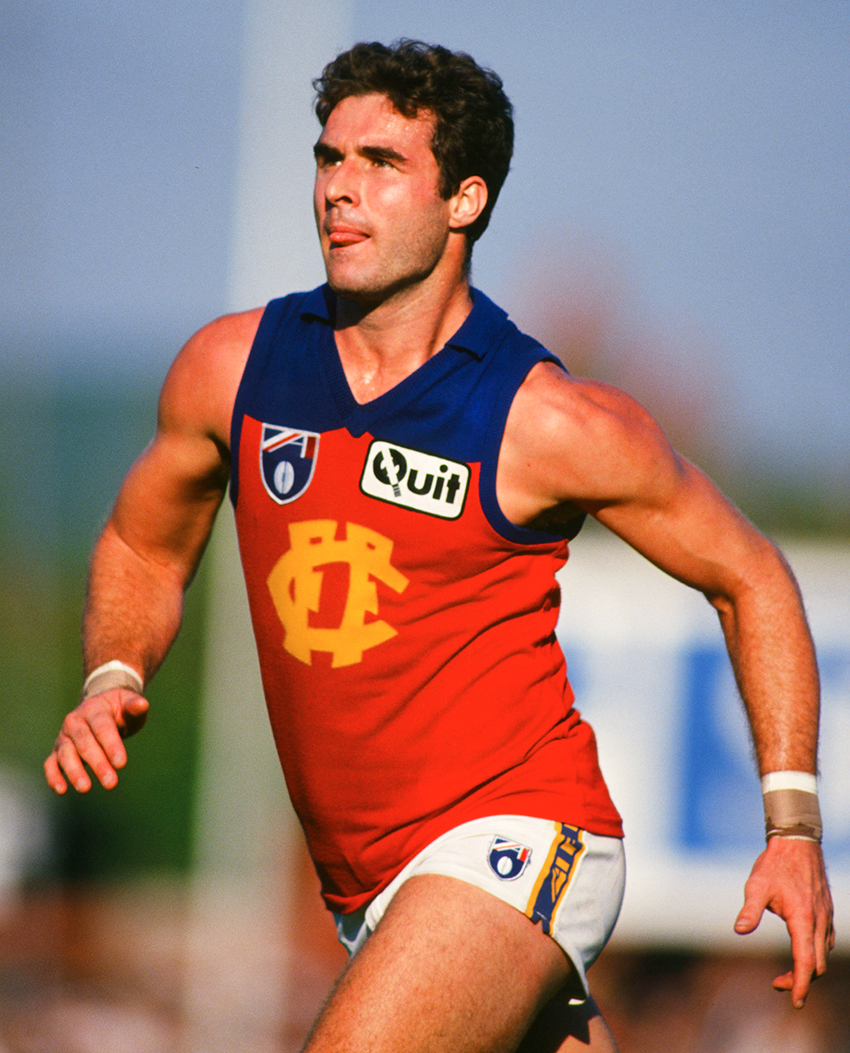

Let's pretend this never happened...

But Shaw also highlighted after 1990 that his injuries might one day cost him: "It will be a year by year thing with him because of what he has gone through."

Manson played 20 matches the following year, including kicking a bag of five goals against Adelaide - five straight again - at Victoria Park. But he struggled in 1992 as Monkhorst clearly bedded down the No.1 ruck slot.

Starved of senior opportunities at Victoria Park, Manson was traded to Fitzroy at the end of the 1992 season, and went on to play three seasons and further 47 games with the Lions. But his heart always remained at Collingwood, where he would eventually become a life member.

That’s the way Magpie fans prefer to remain the man they affectionately called 'Charlie' and whom his teammates used to call "Killer".

Shaw said of Manson: "What can I say about him? I love him."

Collingwood fans will forever say the same.