If Len Thompson redefined the role of ruckman in the mid-to-late 1960s – and he did – then Peter Moore took it to a whole new level just a decade later.

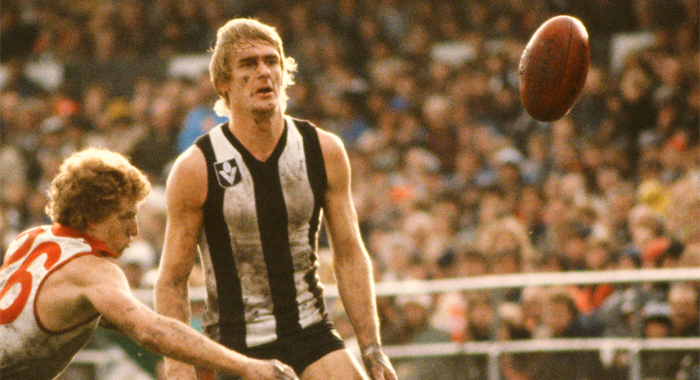

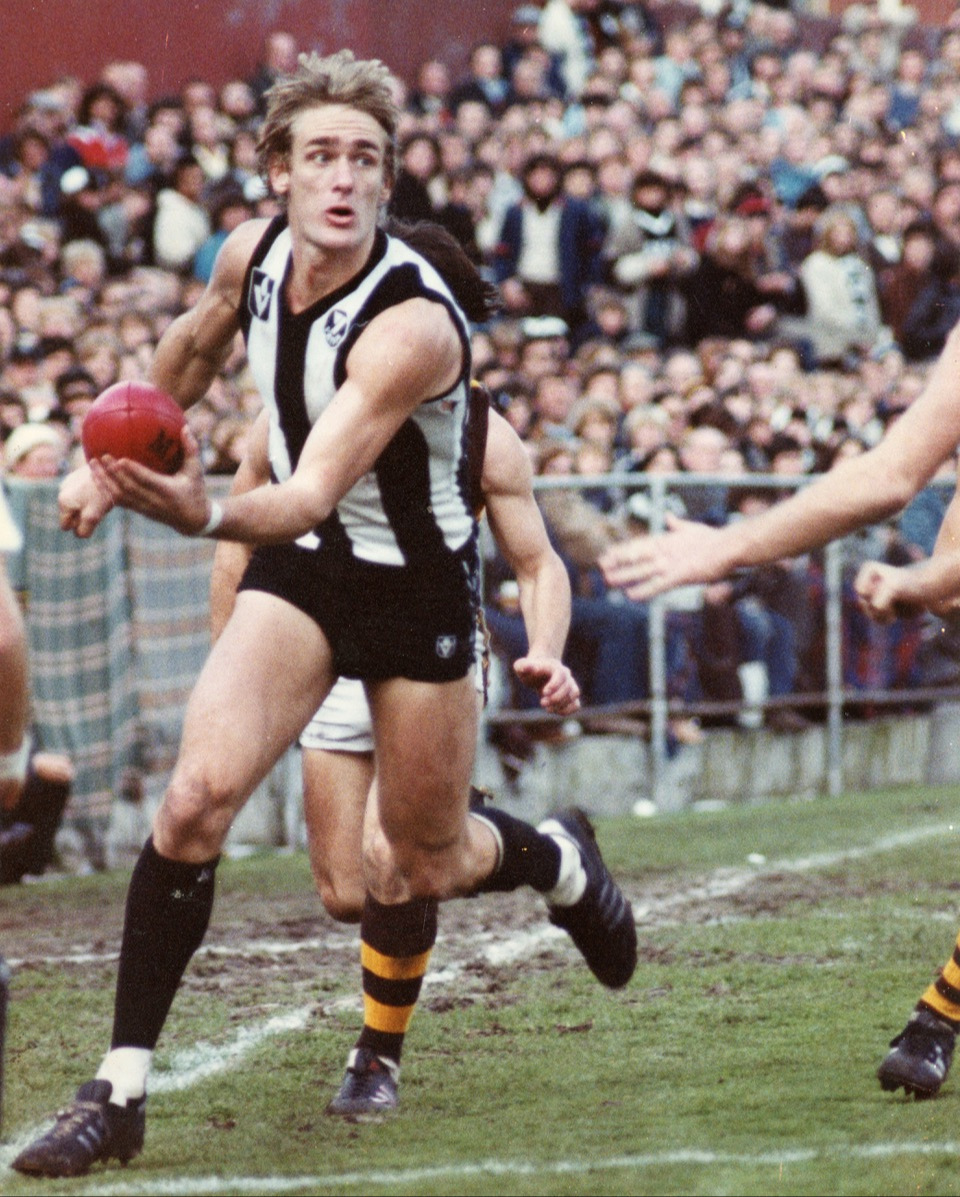

Moore stood at 198cm (6ft 6in) and played most of his career between 98.5 and 105kg (15.5-16.5 stone). He cut a lithe figure on the field, and could run like a deer. He was quicker and more mobile than Thompson, and could leap in a way that previously had only been the province of smaller men. He could kick or handball well on either side of his body, and his ball-handling skills would have done a smaller player proud.

He was never the skilled tap ruckman that Thommo was, but then again this was a man who had spent much of his first few League years at full-forward or centre half-back. Peter Moore was simply a stunning natural athlete who also happened to be outstanding at football. The results, for a few years at least, were breathtaking.

Moore’s natural athleticism had been apparent from an early age. At school he could run and jump with the best, and he played basketball for a Victorian under-14 team. But his footy skills were ordinary, and in his first taste of competitive footy (Eltham under-13s) he was consigned to a second-string team.

But his game developed to the point where, just a couple of years later, he was playing decent footy for Eltham under-15s on Sundays and the under-17s on Saturdays. He was inconsistent, but the talent was beginning to show. Collingwood approached Moore when he was only 14, but his mother thought he was too young — a decision that was to embarrass him some years later.

One day, when the senior Eltham team decided they needed a full-forward, they looked to Moore to fill the breach. He starred — but paid a price. He played only half a dozen or so games, and kicked seven or eight goals in most of them. That was enough to make him realise he could compete against men, and that perhaps he did have the ability for a shot at the VFL. But his opponents soon realised that Moore was just a babe in football terms, and the back of his head suffered. He was frequently knocked out in his short stint with the seniors, and when he began to experience headaches and blurred vision, the doctors ordered him away from football fields for the rest of the season.

The next year he decided to have a crack at Victoria Park. Even though he was seriously intimidated by his surroundings, and the presence of childhood heroes like Thommo, he still ended the practice matches being named on the senior list. During the jumper presentation, coach Neil Mann innocently told the assembled onlookers how Collingwood had tried to get Moore down earlier but had been baulked by his mother: Moore was ribbed about it for weeks.

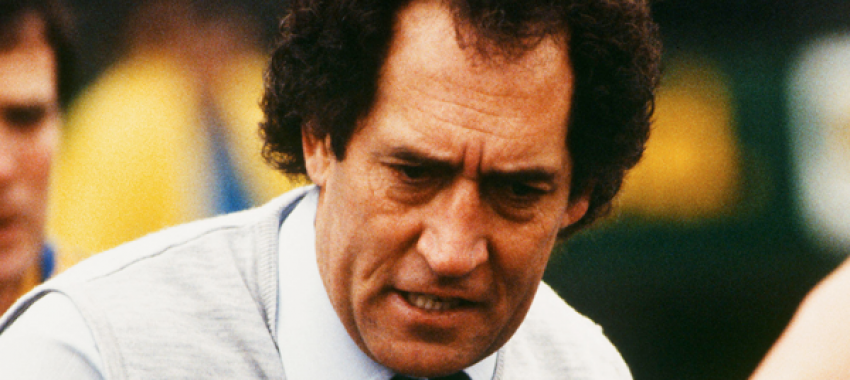

Moore spent most of 1974 in the reserves, finishing second in the best and fairest count. He did manage to play four senior games at the end of the year, three of them on the bench, and did enough to win the trophy for best local recruit. Over the next two seasons, Moore played mostly senior football, but did not really consolidate his spot or make one position his own. He spent time at centre half-back, in the ruck and in the forward line. He often showed potential but lacked consistency, and it was only when Tom Hafey arrived on the scene in 1977 that it all came together.

Hafey had seen Moore play during one of his sojourns forward, and obviously liked what he saw. The idea of a big man in the goal square fitted well into Hafey’s game plan, and he had no hesitation in nominating Moore for the post. The result was two years of exciting football, dotted with some spectacular marks (including a Mark of the Year contended over Mike Fitzpatrick in 1978) and 133 goals. Moore soon became Collingwood’s new match-winner, and the fans warmed to his play. As the ball would come into the forward line, the crowd would begin to “buzz” in expectation of another huge leap or a strong mark. Although his kicking was initially inaccurate, hours of practice with Ron Richards paid off and vastly improved his rate of return.

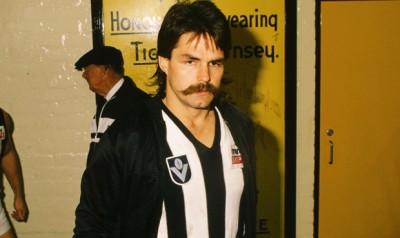

In 1979, with Len Thompson having been shunted off to South Melbourne, Moore moved into the ruck. With the confidence born of a couple of years of regular and successful League football, Moore dominated ruck contests for the next few seasons. He won the Brownlow Medal in 1979 and finished fourth in 1980 (a year in which he still maintains he played the better football). He also won the Copeland Trophy in both years.

Moore’s natural athleticism, his great spring and sure hands were just as potent weapons in the ruck as they had been up forward. He was not a great palmer of the ball, but some of his thumping punches from centre bounces were as good as a kick. His natural fitness allowed him to run all day, and his pace, mobility and quick recovery almost gave Collingwood an extra ruck-rover.

In 1981, Moore’s outstanding efforts were further rewarded when he was entrusted with the captaincy. And while he became a more rounded, team-focused player as a result, and finished third in the Brownlow again, by the end of the year things had begun to go horribly wrong.

Moore played in the 1981 Grand Final with a torn hamstring when he was clearly unfit. Moore, Hafey and the selectors all copped plenty of criticism after the Pies lost the game, and Moore was quick to take responsibility for the decision.

But 1982 was even worse. The bond between Hafey and his players eroded, the team lost nine of its first 10 games and everything pretty much fell apart. Hafey, still remarkably popular with the fanbase, was sacked. And Moore was portrayed in some sections of the media as having played a significant role in that decision. With morale at its lowest ebb in years, the team losing and some fingers unfairly being pointed at him, Moore became disillusioned. At the end of the year, faced with a big money offer from Melbourne, he left. And while he played well at Melbourne, well enough to win a second Brownlow, he never quite hit the heights he had with Collingwood.

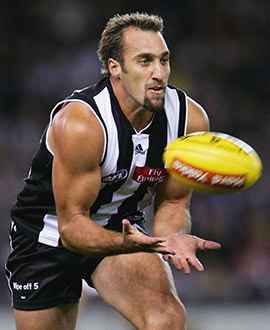

At his best, Peter Moore was a thrilling, unstoppable force who was a star in one of the Magpies’ strongest eras. The slightly messy end to his time at the club seems thankfully consigned to history – especially now that his precociously talented son Darcy has started to forge his own path here. And that has left us with untainted memories of one of this club's most exciting players.

- Michael Roberts

x2

x2

x2

x2

x2

x2

x2

x2