by Michael Roberts

Those behind the push to form the Collingwood Football Club had only a week between the meeting at which Britannia had agreed to support them, and the meeting of the VFA at which they would present their case. But they weren't worried: they felt they had a strong case and would be able to convince the VFA's committee of its merits.

But two hurdles emerged almost immediately – one procedural and the other social.

The first concerned the number of clubs in the VFA. Fearful of its ranks being swelled by uncompetitive clubs, the Association had earlier that year introduced a rule limiting the number of participating clubs to 12 (plus three in Ballarat). As things stood, it seemed that Collingwood would need a club to drop out and create a vacancy before it could be considered for inclusion. Either that, or the VFA would have to change its rules.

The second hurdle was perhaps even more significant, although less overtly obvious. There is no doubt that Collingwood's social standing cost it dearly. There was a prejudice against the slum dwellers having their own football team to play against established clubs such as Essendon, Melbourne, Carlton and Geelong.

This led to a campaign being waged against Collingwood's admittance to the VFA. That campaign started almost as soon as news of the June 7th meeting came to light. And it was led by the Evening Standard newspaper, which pulled no punches in its opposition, mocking the motives of those behind the push and declaring that, "although the dignity of Collingwood would be raised by the possession of a senior football club", it could not and should not be allowed to happen. This was, the paper said, a "useless errand" and one which would only see people "bumping their heads against stone walls."

As the campaign against Collingwood intensified, it also broadened. The Standard questioned, for example, whether Britannia really had been successful enough to justify inclusion ahead of a rival junior team such as North Park, which had won four junior premierships (but had no ground of its own and did not represent a distinct suburb).

Papers like the Standard weren't brazen enough to openly object to Collingwood's admission on the grounds of social status. But the bias was real: you could see it in the mocking tones and condescending language used whenever Collingwood's bid was discussed. 'A place like Collingwood could never have its own football club, so why bother trying?' seemed to be very much the tone of the articles.

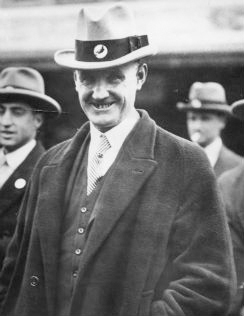

The Collingwood forces began fearing the impact the attacks would have on delegates considering their application. So Alf Manfield, becoming an increasingly important figure in the pro-Collingwood movement, felt compelled to write to the Mercury and other papers, stressing that it was not Britannia that was seeking a spot in the VFA, but Collingwood.

"The Evening Standard having been so persistent of late in doing all they can to thwart our movement, and with their articles trying to influence the delegates of the Victorian Football Association, it is only fair that something should be said on the other side, and why we should receive the association's support," he wrote.

"I wish to point out that it is not the Britannia Football Club, but a Collingwood Football Club, who wish to be represented on the Victorian Football Association, and this club [Britannia] is co-operating with us in the movement, and would form a nucleus for the proposed new club. It is hardly expected that all the junior members now playing would form the senior twenty. Players living in the district and others would join us. We would have a ground of our own, which some of the clubs now on the association cannot say, and for easy access would be second to none in the colony. It is the oldest suburban city having a population of over 30,000 people. The ground is certainly large enough and enclosed, and very easily converted into a first-class playing ground, the surroundings of same being pleasing to the eye, and where is the suburb or any place that supports football better than Collingwood, aye, or even any other outdoor sport? I would ask now what district do the North Park represent, have they an enclosed ground?"

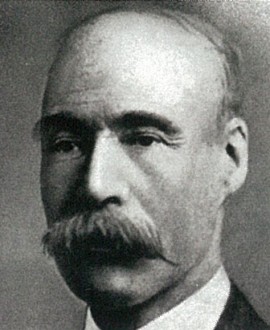

Manfield's arguments, and those of his other supporters, seemed to have done the trick. The VFA meeting on June 28th, held at Young and Jackson's Hotel in the city, heard from local MPs George Langridge and William Beazley, among others. Beazley said that, through Britannia, they had a junior club that met the VFA's criteria in terms of membership and financial security, and that its 'merits in the field' had been sufficiently proved. They also had a ground that could soon be brought up to senior standards.

The initial response was positive. The VFA said that night assured the deputation that their claim would receive "full and fair consideration". The Chairman said he was personally in favour of it. Melbourne's delegate, Mr. A. Hunt, later gave notice that he would move at the next meeting that the Britannia Club be admitted to the association in the name of the Collingwood Football Club.

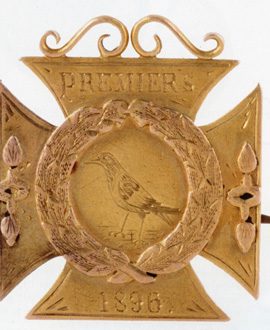

Collingwood's supporters were rightly encouraged. But they seem to have underestimated the power of the campaign waged against them. At the VFA's next meeting two weeks later, a majority of the delegates decided that the association "was already a sufficiently large body, and, on the ground that the Collingwood club could not be admitted while other clubs anxious to join were refused, the resolution moving their admission to the association was lost by 12 votes to 8."

The Sportsman questioned the decision: "Some persons think the association might have stretched a point in this instance; others fancy the delegates decided thus from a loyal attachment to their own rules, which they rigidly enforce – when it suits them."

Collingwood's supporters were stunned, and the local residents dismayed. It had been just over a month since that initial meeting at the City Hotel. Just over a month. And already the Collingwood Football Club as a concept seemed to be dead in the water.