Wes Fellowes was in many ways a football enigma at Collingwood.

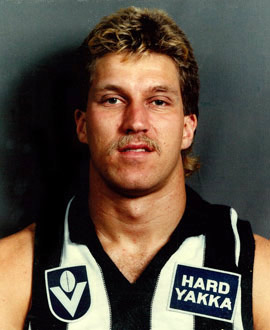

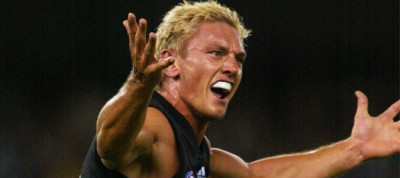

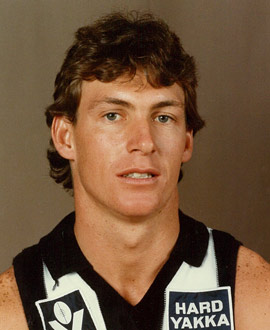

The powerfully-built ruckman with a Black and White pedigree earned the club’s highest individual honour in a season in which he even scored an invite to the Brownlow.

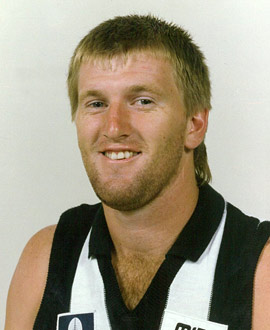

By the time the next season started, however, he had been dropped back to the reserves. Seemingly, throughout his entire 10-season, 102-game career with Collingwood, his place in the senior side was on a knife’s edge, as he competed for a spot against the likes of big men David Cloke, James Manson and, later still, a young Damian Monkhorst.

Such was the frequency of Fellowes’ revolving door between the seniors and reserves following his 1986 Copeland Trophy win that the Coodabeen Champions penned a song in his honour. It was written to the tune of Abba’s Fernando, and was titled ‘You’ve been dropped again, Wes Fellowes.”

Even through his most celebrated season, he came in for criticism from unforgiving fans – and sometimes even his coach – for his attack on the ball and competitive edge.

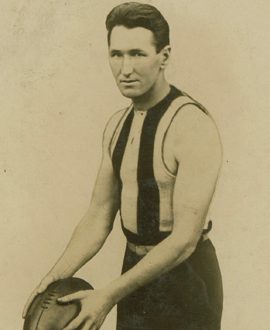

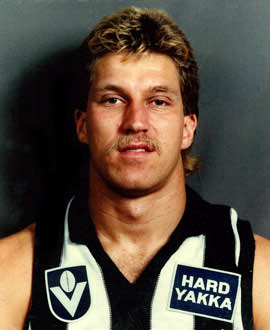

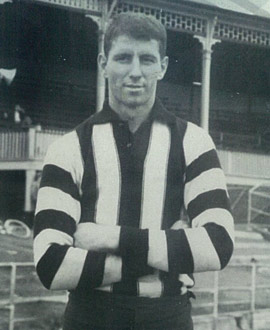

Wes inherited his Black and White connection from his father, Graeme, who was a member of Collingwood’s famed 1958 premiership side.

Graeme, who had played 66 games across eight seasons, once acknowledge his son’s passion for the club, saying: “he was born and bred Collingwood.”

The other thing he inherited from his father was a giant frame – both stood 200cm. But as Wes spent more and more time in the weights room at Victoria Park, he transformed his frame into an exceptionally powerful one, only heightening the calls from the outer for him to use it more.

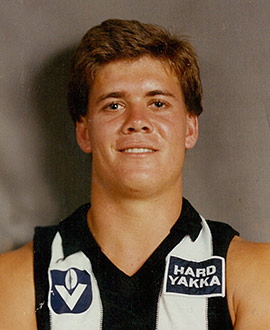

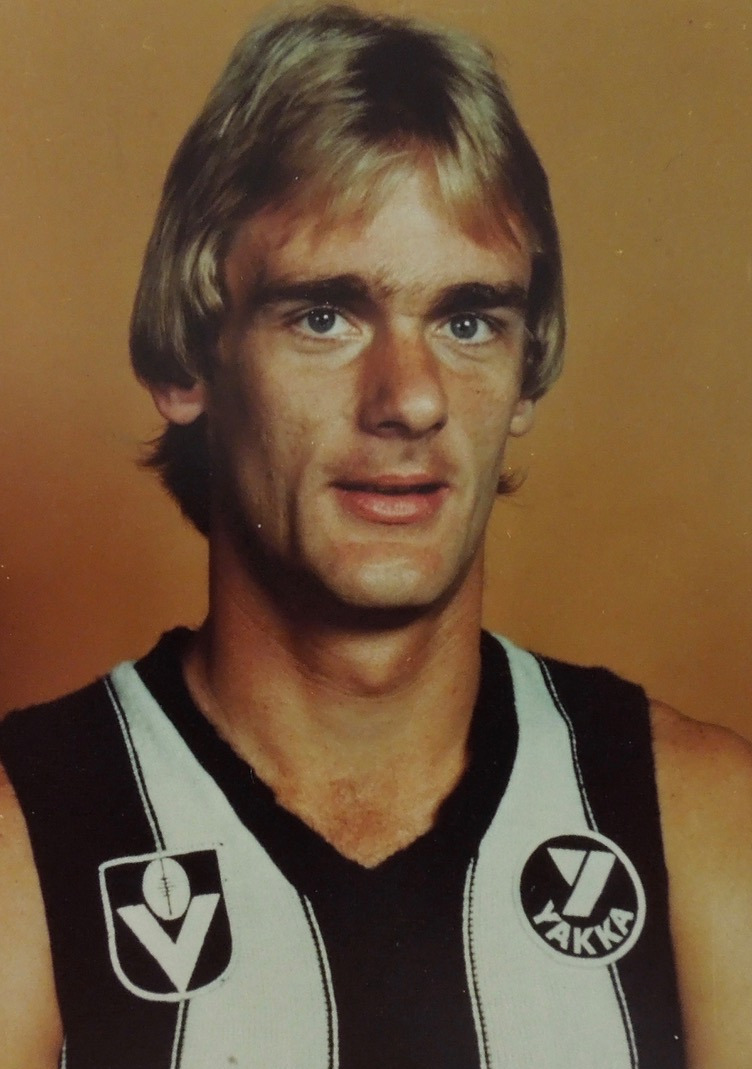

Having been recruited from Bulleen-Templestowe, he made his senior debut as a 20-year-old in round 13, 1981, against St Kilda at Victoria Park. It was Peter Moore’s 150th game and there were hopes that the debutant – who kicked a goal – might one day be able to take over the ruck mantle.

Fellowes didn’t get another chance that season. But when Collingwood imploded and tumbled down the ladder the following season, he had more regular game time, playing 16 games and having 320 hit-outs in 1982.

But his body let him down over the next few seasons. In 1983 he had cartilage removed from his knee, restricting him to 13 games. Then ankle surgery in 1984 kept him to 12 matches, though he regained his spot late in the season to play in all three finals.

He enjoyed a strong second half of the season in 1985, polling 10 Brownlow votes, the same tally as Cloke. That season appeared to give him the confidence he needed and he repaid the faith of the selectors in 1986 by playing all but one man as the first choice ruckman.

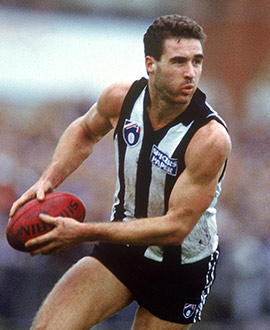

Considered a strong tap ruckman, a solid mark around the ground and relatively dependable with his disposal, Fellowes had a strong season. While he polled four fewer votes in the 1986 Brownlow than the previous year, he was a clear winner of the Copeland Trophy, scoring by 11 votes from Bruce Abernethy and third-year player Darren Millane.

His form was such that one of the league’s new franchises, Brisbane, made him a lucrative offer that he dismissed out of loyalty to the club. It would be a decision he would later question as his opportunities diminished over the following years.

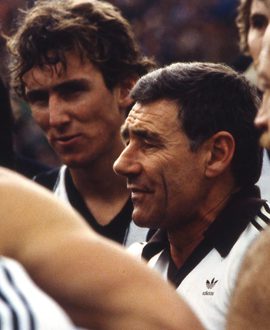

Coach Leigh Matthews challenged Fellowes to be more aggressive after his Copeland success, as well instructing him to stop turning back on the play. In the pre-season after, Matthews said: “Fellowes had an up-and-down season, despite winning the best and fairest. He can be a more valuable player.”

It was hardly the ringing endorsement for the reigning club champion winner, who was just about to turn 26.

Fellowes was left out of the senior team for the round one, 1987 clash with Sydney – a precursor for what was ahead. He managed 17 games that season, but slipped back to only five games in 1988 and just a solitary game in 1989.

The expectation of the Collingwood faithful turned to frustration. They questioned why someone as physically imposing as the 106kg big man did not always use it.

One newspaper explained: “When you are as big as Wes, the public’s expectations are always just as big. When your name is Fellowes, they are twice that size.” And even media commentator Lou Richards conceded: “Too often, too easily, Fellowes falls out of the game, and the Magpies’ hopes crash with him.”

To his credit, Fellowes never complained publicly, even when the criticism was at times too personal and occasionally unfair due to his limited opportunities.

“I guess sometimes it could be true, but I go for the ball, that’s the way I play,” he said of the criticism of his aggression. “But if someone hits me or a teammate, I’ll just go and hit them back if I have to.”

“I say I’ll be out there trying my hardest. You can’t do any better than that, can you?”

There was talk – denied by the club – Fellowes, Ron McKeown and Athas Hrysoulakis were considered for a trade that never happened with Footscray’s Tony McGuinness.

Cloke returned to Richmond in 1990, and Manson and Monkhorst locked in the ruck roles, leaving Fellowes on the outer – again. He did not play a senior game in a drought-breaking premiership season that he had often dream about.

He was delisted in March 1991, after the club had allowed him to keep training to keep in shape as he looked to other opportunities at a rival AFL club. Sadly, that never came, and he was overlooked in the draft. That surprised his first coach at Collingwood, Tom Hafey, who said: “I am absolutely staggered he wasn’t drafted.”

In keeping with his character, Fellowes didn’t lash out at the club or cry foul, but admitted to a little frustration with how he was managed.

“I suppose people didn’t want to play me,” he said. “It was their choice whether I played or not. I suppose I’m sorry I didn’t go (elsewhere earlier), but that’s the way it goes.”

He signed a two-year deal with Port Adelaide in the SANFL and enjoyed a strong season, in 1991. But he didn’t take up the final year of the deal and opted to return to Melbourne to concentrate on his professional career with the tax office, rather than football.

But with a Copeland Trophy on his mantelpiece, Fellowes' place in Collingwood's history will live on forever.