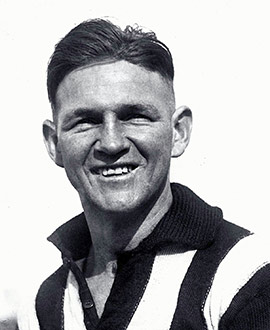

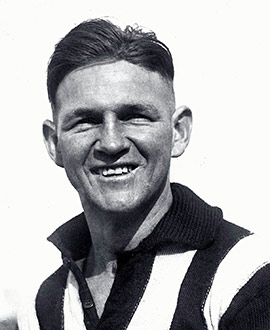

Harry Collier has one of the game’s great CVs: more than 250 games, nearly 300 goals, six Premierships, two Copeland Trophies, a Brownlow Medal, five years as captain, multiple Victorian guernseys. There isn’t much he hasn’t done, or achieved.

But Harry Collier’s value to Collingwood could never be measured in stats or trophies, no matter how impressive they might be. For it was players like Harry whose love for the guernsey helped provide the famed “Collingwood spirit” — that intangible element that helped carry the club to some of its greatest triumphs.

In Harry’s case, that passion for Collingwood was born of a rich local history and a fanatical love for sport, especially football. He was one of ten Collier children born and raised in and around Collingwood, and he attended the Victoria Park school across the road from the football club. Every night after school Harry and his younger brother Albert would duck across to the ground for a kick, to watch training or just to see what was going on. As a result they would invariably get home late, to be greeted by some stern words and “a bit of a kick in the pants”.

Nothing could deter the Collier brothers. Every spare minute was spent at Victoria Park. At weekends they would sell footy records outside the ground, earning just enough money to buy a couple of meat pies. Whenever possible they would organise matches involving other local boys; the participants put in sixpence each to share in the purchase of a footy from Tom Sherrin. These and the school matches provided the Collier boys with a good grounding. During summer they were almost as keen on their cricket, and both were also keen on swimming and running. They were both champion schoolboy athletes who excelled at a range of sports.

But it was football which really captivated them. From the time he was old enough to peer over the pickets at Victoria Park, Harry lived in the hope of playing for Collingwood. Like all Collingwood kids he marvelled at Dick Lee, but later became a fan of the team’s centre line players Tom Drummond, Bill Twomey and Charlie Pannam. In 1921 he made his first major advance as a footballer, winning selection in the schoolboys’ carnival team that travelled to Sydney. A few years later Harry and Albert came under the coaching of former Collingwood player “Snowy” Lumsden at Ivanhoe in the subdistrict competition. Harry won the best and fairest at Ivanhoe in 1924, but his most precious memory of his time there was the day the team was short of players and all six Collier brothers took the field together.

Harry’s performances at Ivanhoe earned him an invitation to try out at Collingwood in 1925. After some early promising practice match performances he damaged a knee and missed most of the year, coming back to be part of the seconds’ Premiership win.

By this stage Albert had overtaken Harry and played a few senior games. In 1926 Harry’s dream finally came true when he was chosen to join his brother in Collingwood’s seniors for the third game of the season against Hawthorn. It is hard now to convey just how important that selection was to Harry. He had Victoria Park blood running through his veins, and had no more intense ambition in life than to be a Collingwood footballer. He could not believe it when he learned he would be paid as well. He thought you did it for nothing, and would probably have paid for the privilege if necessary. To play for Collingwood meant everything to him, and that was reflected in the desperation and commitment in his play.

He was only about 173cm (5ft 8in) and 66.5kg (10st 71b) but that never worried Harry; he threw himself into the fray with total disregard for his own physical wellbeing. A reporter once described Harry as being “as game as you can make them and persistent as a fox terrier after a rabbit”. Another reporter once wrote that the only thing wrong with Harry’s game was that “his pluck would sometimes take him into dangerous situations where only heavier men should go”. Harry would not have seen that as a failing.

Despite his small size Collier was surprisingly strong and very, very tough. Former Richmond rover Maurice Hunter rated Harry his most difficult opponent. “Harry had all the attributes of a champion, with pace, pluck, skill, tenacity and brains,” Hunter told The Sporting Globe. “In addition, he could take and give hard knocks.”

Harry was not particularly fast but he was elusive, rated as a master of blind turning and twisting. He also had excellent skills, being a superb ball-handler and a good kick with either foot who was particularly dangerous near goal. His anticipation was superb, and his judgement of the ball off packs especially good. Supporters and players of the fifties would later liken the great Bob Rose to him, and that is indeed a hefty compliment — for both players. Collier was wonderfully consistent, playing his first 100 games in a row and always playing well in the big matches.

His outstanding performances were rewarded with the Copeland Trophy in 1928 and again in 1930, the same year in which he would retrospectively win the Brownlow Medal. He frequently represented the State and won numerous club awards. His dedication to Collingwood was further demonstrated by the special award given to him in 1935 for his remarkable achievement of missing only one night of training in ten years.

Perhaps his greatest reward came when he succeeded Syd Coventry as captain. He was an ideal choice; respected, inspirational and levelheaded enough to know when to settle his players down. Collier’s vice-captain was his brother, and the two provided an outstanding leadership team. They looked after young players on and off the field, made sure they got a kick in their early matches, tutored them in the skills of the game and basically imbued them with the club spirit. When the two led the Magpies to the 1935 Premiership over South Melbourne it provided Harry with one of his most treasured footballing memories.

Its aftermath, though, led to one of his most embarrassing. Coming home from the post-match celebrations, Collier drove his car into Archbishop Mannix’s fence. He hurriedly backed the car up and drove away, but in doing so left its bumper bar wedged in the fence. As well as having to later apologise to Archbishop Mannix, the Collingwood captain had to endure the embarrassment of fronting up to the Kew police station to retrieve his bent bumper bar.

After winning flags in his first two years as captain, Harry led the team into losing grand finals in the next three. In 1938 however, he was not there to join the battle on grand final day, having been controversially suspended for a massive 14 games for belting a Carlton player. The sentence was manifestly unjust, but even a 2500-strong petition did not succeed in having it reviewed.

If anything the incident made Harry even more popular with Collingwood supporters. His gameness, pluck and feisty nature had always made him a favourite at Victoria Park. So, too, had his down- to-earth attitudes, his unquestioning loyalty to the club and his willingness to give anything for its success. All of which made it even harder for Harry to accept when he and his brother were told to retire shortly before the 1940 season.

Harry, Albert and the rest of the players had — perhaps unwisely — become involved in the 1939 club elections. They publicly backed the existing committee against a challenge group, arguing that stability was in the best interests of the club. With their help the committee survived, but only months later “thanked” the Colliers by telling them their services were no longer required. Harry was deeply hurt by the decision, but would later return to the club as long-serving committeeman and talent scout.

Collingwood’s fortunes slumped dramatically without the Colliers. But that’s not surprising; rip the heart out of any body and it will have trouble functioning. And Collingwood did lose part of its heart when it lost Harry Collier. For years he had been central to the soul and lifeblood of the team, epitomising all that is famous about the Collingwood Football Club.

In his later years he became a sort of symbol to the younger generations of what the old-timers meant when they talked about the famed Collingwood spirit; in the form of Harry Collier that spirit could not have had a better standard-bearer.

- Michael Roberts

CFC Career Stats

| Season played | Games | Goals | Finals | Win % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1926-1940 | 253 | 299 | 27 | 76.3% |

CFC Season by Season Stats

| Season | GP | GL | B | K | H | T | D | Guernsey No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Other CFC Games

| Team | League | Years Played | Games | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collingwood | Reserves | 1925 - 1926 | 21 | 20 |

Awards

x5

x5

x2

x2

x3

x3

x6

x6