By: Glenn McFarlane

“Well, I don’t feel any different, but it is a grand thing to have done,” Gordon Coventry, June 4, 1934.

Collingwood and Geelong played out a rare draw in 1934.

And the result was not the only momentous thing to happen on that long ago, almost forgotten winter’s afternoon at a ground that no longer holds league matches.

A history-making moment was a part of the day and something that had never happened before.

For that was the day that Collingwood’s greatest goal-kicker Gordon Coventry closed in on one of the most remarkable feats seen in football to that stage.

As he and the Collingwood team boarded the train for Geelong at 12.20pm on the day of the game, the expectation was that Coventry would smashed through the 1000-goal barrier in the match at Corio Oval, which was Geelong’s traditional ground.

The venue would be replaced at the end of the 1940 season, as it was seconded for war use, with the Cats to call Kardinia Park home.

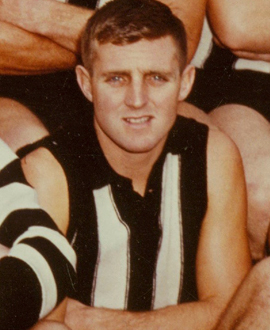

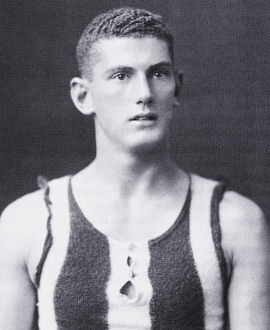

Coventry was 32, and was about to play his 239rd game in Black and White.

Incredibly, 160 of those had come in winning sides, and his goal tally had pushed to 998, leading into the game.

The match was played on a public holiday Monday, on June 4, 1934, when the two teams in second (Collingwood) and third spot (Geelong) were battling to out to keep in touch with South Melbourne (top).

As the Magpies arrived at the ground, eager to make a statement, the crowds anticipated a cracking game, with many of them streaming off the three special trains that had come from Melbourne.

The Argus anticipated a keenly-fought clash between the two teams who had won five flags in the previous seven years (four in a row for the Pies from 1927-30, as well as one for the Cats in 1931).

It recorded: “Twenty-one thousand people were moved to a high pitch of excitement...expectations of a close finish could not have been more fully realised.”

Collingwood had to make do without its star pivot Jack Beveridge, who had injured his knee on the Friday before the game, with Horrie ‘Tubby’ Edmonds elevated to take his position.

The Magpies had an exceptionally strong team.

Its 19 players – including Alan ‘Ginger’ Ryan, a former Melbourne player, who was the reserve player that day – had played a total of 1525 games. Seven had played 100 or more games – Gordon Coventry (238), Syd Coventry (218), Charlie Dibbs (184), Albert Collier (157), Harold Rumney (144), Harry Collier (123) and Len Murphy (113).

To put into context Gordon Coventry’s impact at the time, the team leading into that match at Corio Oval had kicked a total of 1696 goals. Coventry had kicked 998 – or almost 59 per cent of them.

The Australasian highlighted some of the anticipation that led up to the match, saying: “so intense was the interest taken in the meeting of Geelong and Collingwood that it attracted an attendance of 21,000.

“It was a real test for both teams – a desperate and thrilling game, and wildly exciting in the last 25 minutes as the issue just kept see-sawing from one side to the other.”

Contrary to the norm for visiting teams at Corio Oval, Collingwood made a positive start to the game. Usually, it was Geelong who held the upper hand in matches on their own dunghill.

“The visitors went off with a rare burst”, which gave the Magpies a clear and decisive lead at the end of the opening quarter. Albert Collier and Len Murphy gave some early highlights with some high-flying efforts, but it was Harry Collier who kicked the opening goal of the game.

The elder of the Collier brothers produced “one of his favourite tricks – he makes a point of being handy when the tall men crowd Gordon Coventry” and made no mistake in slotting it through.

Magpie skipper Syd Coventry had already signalled 1934 would be his final season. So, on this last visit to Geelong as a Collingwood player, he started well, kicking the second goal of the contest.

While the Cats could only manage one goal in the first term, Collingwood applied some real scoreboard pressure on the home side.

The next two goals came from an unlikely source. Both were from Norm Le Brun, a 26-year-old already at his fourth club (there would be one more to come), who was making a real impression in only his seventh game in Black and White.

The Argus wrote: “Le Brun’s shrewdness and dash enabled him to snap two goals in quick succession and the fifth was gained when H. Collier passed to S. Coventry, and Coventry reciprocated as Collier ran into position near goal.”

The margin was 28 points at quarter-time, as the Magpies’ 5.4 clearly overshadowed the Cats’ 1.0.

The second term saw Collingwood start to “throw their weight around”, but the game became even tougher as Geelong’s players were more than willing to give a little bit of their own back.

But the home side changed the context of the whole match, kicking six goals to three to claw their way back into the game.

The first of the Pies’ second term goals came from Gordon Coventry after a “bullet-like stab kick by M (Marcus) Whelan to H. Collier went onto G. Coventry” for his 999th goal.

He looked certain to kick his milestone goal shortly after before defender George ‘Jocka” Todd “no doubt with some compulsion, drove the ball away in a flash.”

However, it would come soon enough.

Coventry was back into action shortly after when he obtained a kick from Jack Ross and slotted through a goal that the whole crowd – yes, even Cats’ fans – wanted to see.

The first man to congratulate Coventry – a man who rarely made a fuss of things – was Geelong’s Todd.

It was the first time any man had passed the 1000-goal mark, though Coventry was more interested in winning the match than celebrating his individual feat.

Coach Jock McHale, never a man disposed to highlighting individual laurels, would barely have mentioned the milestone in one of his legendary half-time speeches.

The difference at half-time was only eight points in Collingwood’s favour.

By three-quarter-time, Geelong had wrested it back to four points. Champion defender Jack Regan was shifted out of the full-back role for a period after struggling to keep tabs on his opponent. He was replaced briefly by Albert Collier, and then by the Machine full back Charlie Dibbs, who tended to play in the back pocket in the last few years of his career.

It looked as if Collingwood would gain the lead early in the last term when Edmonds, who had moved to full-forward in place of Gordon Coventry, who went out to half-forward, missed from point blank range – as Magpie supporters “groaned”.

Worse still, Syd Coventry had to sit out the last quarter after going off with a leg injury, leaving Ryan to disperse with the dressing gown and come on in his place.

Amazingly, Ryan would kick a goal a year later which would bring about a draw in a clash with old rivals, Fitzroy, but he wasn’t to be the difference that day.

The Cats went out to a 15-point lead at one stage of the final term, before a long kick from an 18-year-old kid in only his fourth game passed narrowly over the hands of opposition defenders and in for a goal.

The kid was the youngest player on the field that day. His name was Phonse Kyne. He would go on to become a Collingwood great.

Le Brun’s third goal cut the deficit back further. But it was assumed that Geelong had the upper hand as the home side kept the scoreboard operators busy.

The Argus had all but given up, saying: “It seemed now that Collingwood could not possibly catch up.”

The evidence seemed in the Cats’ corner before a hat-trick of goals once more swung it in the Magpies’ favour again.

The goals came from Gordon Coventry, Harry Collier and ‘Tubby’ Edmonds and all of a sudden the difference was back to five points.

And then the man of the moment, Gordon Coventry, stepped up once more as he had done so often over 15 seasons.

One journalist wrote: “The excitement was tremendous when Coventry shrewdly judged a mark, and taking careful aim, kicked the goal that put Collingwood one point ahead – 109 to 108.”

Then, in the closing minute of the match, Geelong’s Lou Daily pushed through the point that levelled the scores before the bell finally signalled a draw.

The Argus said: “Perhaps the best men on the Collingwood side were (Harold) Rumney and (Fred) Froude on the backline, (Marcus) Whelan, on a centre wing, and H. Collier, as rover. All four played dashingly throughout. (Jack) Regan, if less conspicuous than usual, was sound, and (Keith) Fraser, (Norm) Le Brun, (Jack) Ross and (Albert) Collier were the best of the others. Harry Collier and Gordon Coventry had kicked four goals each, with Le Brun (three) and Kyne (two) among the chief goal kickers. The end of the game brought the teams together in terms of the scores, but it was also the case in the rooms after the contest. In a sporting gesture befitting the match, Geelong’s president, Mr M. Jacobs, entertained the two teams, with the Coventry brothers as the “chief guests.”

Syd Coventry addressed his troops and told them the exhibition in the final term was “the best football he had ever seen”, which was something coming from this veteran of the game in his last season.

Gordon, as usual, sat quietly, almost in reflection on what had been a momentous day.

All he would add was: “Well, I don’t feel any different, but it is a grand thing to have done.”

Perhaps there has never been a more humble champion for Collingwood.

But Jacobs ensured that the two Coventry brothers were going to get the attention they deserved, even if they didn’t covet it. He called them “an ornament to the game”, praising Syd for his wonderful career and wishing him well for the end of the season, and lauding Gordon for his remarkable record in front of goals.

The words were accompanied by some gifts – a travelling rug and silver cigarette case for both of them.

The rugs had monograms of the players alongside a Magpie, and the cigarette cases were personal gifts from the opposition president himself. It was a fitting end to a history-making day.

As Collingwood – and the Coventry brothers – rattled their way home on the train to Melbourne that night, there would have been a sense that although there were no winners on the day; football itself had been the real winner.