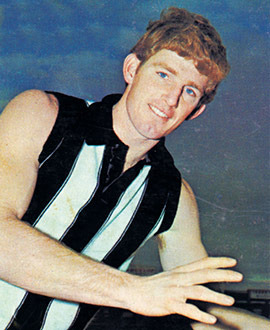

Ernie Wilson was a tenacious, rugged and fearless defender of the 1920s who polarised opinions within the footballing community.

Opposition fans loathed him. They believed he was a thug whose only interest in the game centred around physically disabling opponents. He had a reputation for crashing forwards to the ground after they had disposed of the ball, and was often the target of much abuse from opposition fans.

At Victoria Park, of course, Wilson was viewed in an entirely different light. His teammates respected him enormously, and Magpie fans would not hear a word against him. Nevertheless, the “Is Ernie Wilson a fair player?” debate raged on and off for years, often becoming a major talking point in football circles.

There is no doubt that Ernie Wilson played it tough. But there is also little doubt that he played it fair. He was one who revelled in games that were rugged and physical. His fearless, straight-ahead style of play often led him into heavy physical clashes with opponents, and it was these for which he incurred the wrath of opposition fans. He was suspended several times, most notably getting eight weeks on two counts of elbowing Melbourne players in 1926. But the bumps and clashes, though hard, were usually legitimate, and the opposition fans’ anger unwarranted.

Ernie 'Sugar' Wilson knew only one way to play the game — and that was at full throttle, with scant regard for the consequences to either himself or his opponents. He was a tiny ball of muscle, standing only 168cms (5ft 6in) tall, and weighing 72.5kg (11st 61b), carrying his weight low to the ground. Wilson had big, strong shoulders and exceptionally strong legs. He was renowned as a great dasher from the back line, and possessed rare courage (he once played on despite a badly bruised kidney). When the ball was there to be won, nothing else mattered to Ernie Wilson. A sportswriter once said that he “bucked into each conflict as if his life depended on it”. He would not go around players, always preferring the direct route, and often wound up black and blue with bruises at the end of a match.

In 1925, Wilson summed up his attitude to the game in an article in The Sporting Globe: “If I never had the grit I would be of no use to the Collingwood side,” he said. “The Magpies have no use for any player that lacks determination. Consequently, when I play football I play it with vim but I always go for the ball.”

All of this makes Ernie Wilson sound like one of those honest battlers who is not over-burdened with ability but gives 110% each week. That is the way he was viewed for much of his career, but such an assessment sells Wilson woefully short. In his prime, the stocky defender was one of the game’s most valuable players. In 1927, no less an authority that Syd Coventry proclaimed him to be “the greatest defender in football”. W.S. “Jumbo” Sharland, in The Sporting Globe, said he ranked “as one of the best defenders who has ever played”, and probably the best in the decade after World War I.

Forget Wilson’s own self-deprecating comments; no player earns those kind of accolades on “grit” alone. And an analysis of contemporary newspaper reports and club documents in 2017 confirmed that thought, with Wilson earning two retrospective Best Player awards for his 1923 and 1924 seasons.

His greatest forte was wonderful anticipation. He seemed to be able to sense when an opposing forward thrust was looking dangerous, and had the happy knack of bobbing up in the right place at the right time for a safe mark or clearing dash. He was quite nippy, could turn quickly and could build up a fair head of steam over distance. He was also a good mark for his size, and could kick reasonably well with either foot. He could also intimidate opponents, because of his ferocity at the ball and in packs (although one former colleague also maintained that the sound of his deep gruff voice was “enough to scare you half to death”). As one Collingwood player later said: “If Ernie was anywhere near the ball, you didn’t want to be anywhere near Ernie.”

Magpie supporters have always admired those players who have a “red-hot go”, and they soon warmed to Wilson’s approach to the game. In 1924, when the local Austral Theatre first offered a trophy to the most popular Collingwood player (based on the votes of the theatre’s patrons), Wilson emerged a clear winner. He was also a favourite with his teammates. They respected his performances on the field and enjoyed his company off it. He was always bright and happy, and was reputed to be the life and soul of many a social situation. He was also a great practical joker, and expended a good deal of energy trying his pranks (usually unsuccessfully) on veteran trainer Wal Lee. He worked as a grocer’s assistant in Northcote (and later ran the store), a job that in his early days often made him late for training.

The son of a butcher, Wilson was born and brought up locally and went to Victoria Park State School. On leaving school Wilson joined the Clifton Hill Imperials, where he showed some ability as a wing player. One day he was playing with some other juniors at the Collingwood ground when Alf Dummett noticed him and told the youngster he was impressed. That encouragement was all that Wilson needed. The next year he played at half-back with the South Yarra junior side and, just over a year later, found himself in the Collingwood team for the opening game of 1919 at South Melbourne. He did well, and only an ankle injury suffered during the next week at training stopped him from keeping his place. He played 10 games that year, mainly as a forward. Importantly, he played in the game that counted most — the Premiership win.

He still took a few years to firmly establish himself, and enjoyed his best year in 1924, when he was magnificent at half back, Collingwood's best player and the only Magpie selected in the carnival team that played in Hobart, where he starred.

Wilson’s success in Hobart considerably enhanced his reputation as a player of real talent, rather than just a determined trier, and his game flourished as a result. He continued to turn in fine performances through the next four seasons, and won two trophies (one a biscuit barrel) for his performances in the 1925 finals. Such was the quality of his play that there were some who said he was unlucky to miss the captaincy after Charlie Tyson was dumped for the 1927 season.

The man who edged him out for the captaincy, Syd Coventry, once wrote: “No football club has ever had better service from a footballer than Collingwood have received from Wilson.” Coming from Coventry, that is high praise indeed.

- Michael Roberts

CFC Career Stats

| Season played | Games | Goals | Finals | Win % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1919-1928 | 125 | 8 | 14 | 68.8% |

CFC Season by Season Stats

| Season | GP | GL | B | K | H | T | D | Guernsey No. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Other CFC Games

| Team | League | Years Played | Games | Goals |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collingwood | Reserves | 1932 | 14 | 5 |

Awards

x2

x2