Alby Pannam, more than most, should have felt right at home in the Collingwood change rooms. After all, his father had been a legend of the club in its earliest days, and oldest brother Charlie had been a star just a few years before he arrived there in the early 1930s.

But Alby was small and slight, standing just 170cm tall and weighing only 68.5kg. And as he looked around the Victoria Park clubrooms in his first visits there, all he could see were heavily muscled giants like the Coventrys, Len Murphy and George Clayden. It was intimidating. But Alby wasn't deterred: instead he decided virtually on the spot that there was only one way he would survive as a footballer – and that was by being faster and cleverer and trickier than anybody else in the game.

In the end, that was pretty much what he achieved. By the time he left Collingwood in the mid-1940s he was regarded as one of football's greatest ever rover/forwards, and one of the finest sharp-shooters the game has seen.

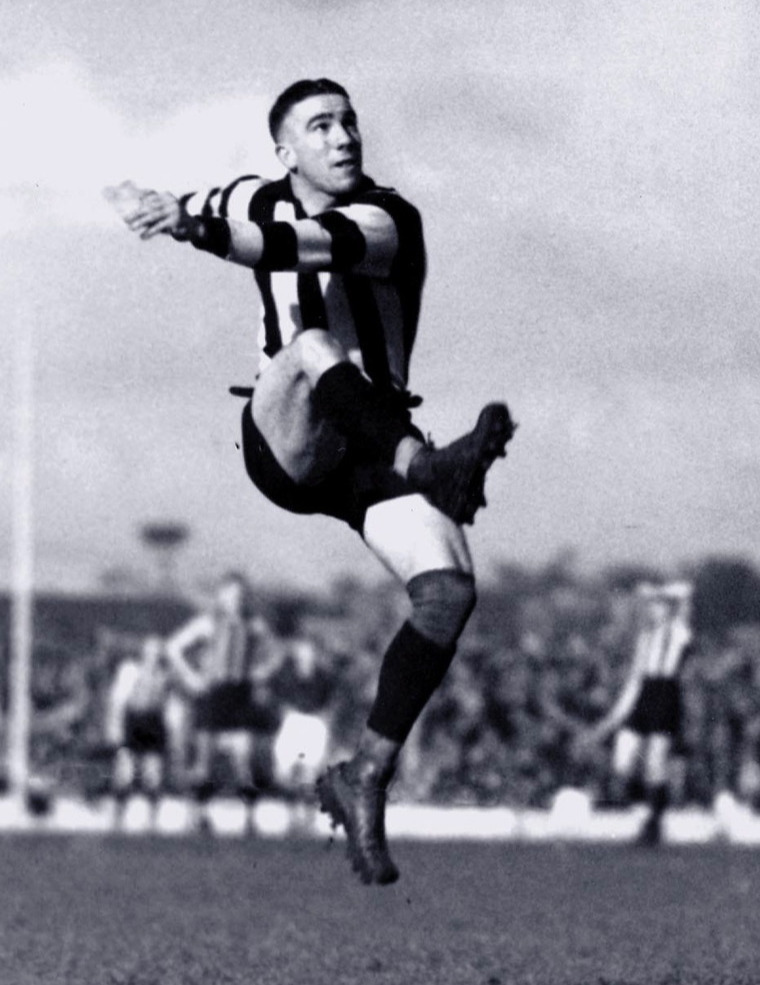

Fortunately, Alby was blessed with all the gifts he needed to compensate for his lack of height and weight. He could dodge, weave, baulk, spin and turn like few others (he always believed he developed these skills as a kid while playing in the rough-and-tumble of street handball and football games). He was super-quick and highly skilled, a good mark for his size and a magnificent kick, not so much in length but in precision with his passing and a freakish accuracy with his goalkicking. His snap shots for goal were something to behold and he was one of the first players to master the art of snap-kicking “around corners” or with his back to goal. Former Richmond defender Kevin O’Neill told theSporting Globethat Pannam was a hard man to mind. “Pannam turns on a threepenny bit,” he said. “Let him get his boot to the ball and he can score with potshots from the most absurd angles.”

As O'Neill found, Pannam was a defender's nightmare – all action, energy and activity, and almost impossible to contain. Plus he had all of the cheeky smart-alec traits that would later be seen in his nephew, Lou Richards. He would yap all day, stirring up opponents and trying to put them off their games (it was a bit the same off the field too, where Alby was regarded as one of the real characters in the dressing room).

The two things most observers recall about Pannam's career are his cheek, and his goals. And fair enough too: he kicked 452 of them in his 181-game career. But it's often overlooked just what a good 'pure' footballer he was too, especially as a rover. In 1947, Essendon's triple Brownlow Medallist Dick Reynolds rated Alby alongside another three-time Brownlow winner in Haydn Bunton as the finest rovers he had seen during his career. “He [Pannam] could turn and twist out of trouble in a flash, and he knew how to create the loose man with his great handball or low punt pass,” said Reynolds. “Then, when spelling in a forward pocket, he was outstanding with his cleverness. The way he could baulk and dodge his opponents gave them little chance of stopping him.”

It was as a midfielder that Pannam got his start as a footballer, playing with Richmond Amateurs as a 14-year-old. He was the youngest of Charlie Pannam Snr's seven children and came through the Collingwood Technical School (where he once kicked 11 goals in a school match). In 1930 the Amateurs' centre line consisted of Alby and older brothers Bert and Eric.

Neither Bert nor Eric went on to League football but Alby was determined to make it. He soon graduated to playing for Abbotsford in the sub-district league on Saturday afternoons, but was so in love with the game that he also played with the Carlton and United Breweries team in the Saturday Morning Football League (winning the competition best and fairest in 1933 despite playing only six games for the year!). Playing two games on a Saturday didn't seem to faze young Alby in the slightest. In fact, he thrived on it.

He had actually trained at Collingwood during the 1933 pre-season before returning to Abbotsford and CUB, but the Magpies called him up to play eight games with the seconds mid-season. He impressed enough for the selectors to give him a handful of senior games late in the year, where he kicked 14 goals in his last four games. He looked set to make his mark in 1934 but struggled with form and injury, managing only six senior games.

But Alby's career-changing moment came in the third round of 1935, his first game back after a suspension incurred the previous year. He came straight back into the seniors against Essendon and booted seven glorious goals. A few weeks later he did the same against St Kilda, and his position was assured from then on. The Sporting Globe was quick to recognise his qualities.

"[Pannam] gave another dashing display and was the best player afield," it said. "His contribution for the day was 7-1, obtained through clever scouting and rare accuracy. He is a brainy footballer who, through lack of weight and inches, has to rely on pace to get him out of trouble. Clever and elusive in everything he does he is a worthy member of one of the greatest football families of the game."

Pannam went on to kick 46 goals from his 15 games that year, a clear second behind Gordon Coventry, and played well in the Premiership victory over South Melbourne, kicking a couple of goals. But he went even better in 1936, worming his way through the South Melbourne defence to kick five goals and win general acclaim as the best player on the ground as the Pies went back-to-back.

By now Pannam was regarded as one of the most dangerous small forwards in the competition. He formed great partnerships with first Gordon Coventry, then Ron Todd, and also fellow magician Des Fothergill. He was remarkably consistent, kicking 46, 45, 49 and 54 goals in his first four full seasons.

It also became clear that, despite his size, Pannam was a rugged and feisty customer. (That much would have been known to anyone who ever watched him play cricket, where he was renowned as a tearaway quick in the first grade of the North Suburban Cricket Association.) The Herald’s Alf Brown described him as “fast, clever, durable, tough, nasty and selfish”. Jack Dyer, who knew a thing or two about toughness, once described Pannam as the "toughest and cleverest" footballer he had ever played against. Indeed Dyer felt Collingwood would have won the 1946 Premiership had Pannam still been at the club.

Unfortunately by that stage he'd left and was leading Richmond's reserves. Pannam had won the Copeland in 1942, finished third in 1941 and three times won the club's goalkicking in the early 1940s. His football time was interrupted by war service with the RAAF (while in Darwin he captain-coached the RAAF side to a flag and was voted the best player in the series), but when he returned full-time for the 1945 season he was appointed captain. Unfortunately he twice injured his knee in the lead-up to the finals, first against Fitzroy then more seriously in a RAAF match, and missed the rest of the year, including the heartbreaking preliminary final loss to Carlton.

Pannam wanted to play again in 1946 but the club had doubts about his knee and cleared him to Richmond as playing coach of the reserves, where he spent seven years and played another 130-odd games (even pulling on the boots for the seniors a couple of times, once kicking six goals). He later coached the Tigers seniors for three seasons, thus creating the unique record of a father and son both having captained Collingwood and coached Richmond.

But Alby Pannam's heart was always with Collingwood. He hadn't really wanted to leave in the first place, and there was great happiness on both sides when he returned to become a big part of Collingwood's Past Players’ Association, an involvement that lasted well over 30 years. He had taken over the mantle from his father and oldest brother and handed it on to the next generation in Lou and Ron Richards. He had done the Pannam family name proud.

- Michael Roberts

x3

x3

x2

x2