By: Glenn McFarlane

In the first half century of the competition, the Magpies and the Swans played in 13 finals. Since, they have played in only one - the 2007 Elimination Final, which was won by Collingwood on its way to an extra-time Semi-Final and ultimately a Preliminary Final.

But the halcyon years of the Magpies and Swans rivalry came during one of Australia's tough times, at the tail end of the Great Depression - the mid 1930s.

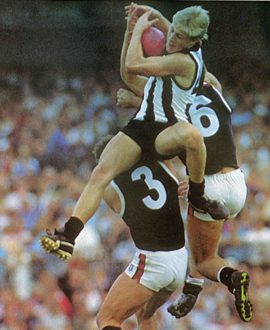

In 1935 and 1936 Collingwood and South Melbourne were the two best teams in the VFL competition. As different as they were in style and substance, the teams came together for four memorable finals - two Second Semi-Finals and two Grand Finals - with the Magpies prevailing in three of the four.

The Magpies were in the process of remodelling the side that had entered football folklore as 'The Machine'.

As much as their legendary coach 'Jock' McHale hated the ‘Machine’ moniker, because he believed it gave a false impression that the team was rigid and inflexible - which it wasn't - it became a part of the football vernacular to express just how close and committed this side was.

This magnificent side had won four successive premierships from 1927-1930, with some of the most recognised names in football all combining for a common dream. Individuality was taboo; egalitarianism was everything; loyalty was paramount; and winning was almost a birthright.

But there had been no Grand Finals berths for Collingwood between 1931 and 1934. In between those years, South Melbourne had emerged as one of the most flamboyant, brilliant sides in the VFL. They were, quite literally, a team of champions, and won the flag in 1933, as well as being runner-up a year later.

Collingwood travelled to Port Douglas for a mid-season hiatus in 2012, but they went alone, and with rest, recuperation and some training sessions in mind.

Just imagine if the Magpies had this year done a deal to head away with a rival side during the home-and-away season to promote the game to the northern states and to try and foster greater camaraderie within the playing group.

It did happen 77 years ago. In late July and early August 1935 Collingwood and South Melbourne went "on tour" together due to a break in the fixture to foster the game in foreign markets.

What it meant was that the two sides came to know each other very well at the time. They played twice in the 1935 home-and-away season, three times on their tour north and twice during the finals series.

Collingwood still had some familiar faces from 'the Machine' heading into the 1935 season. The likes of Harry and Albert Collier, Gordon Coventry, Harold Rumney, Charlie Dibbs and Percy Bowyer were still important players. But the club had also unearthed a number of young players after the 1930 Grand Final, such as Jack Regan (who actually made his debut in 1930), Marcus Whelan, Alby Pannam, Phonse Kyne, Ron Todd, among others.

The Magpies had to find a new captain in 1935. Four-time premiership skipper Syd Coventry had decided to retire. It was always going to be difficult to replace him, but the club believed it had a leader in waiting, in Harry Collier.

South Melbourne had the likes of stars such as Bob Pratt, who had kicked a record 150 goals in 1934, Laurie Nash, Herb Matthews, Jack Bisset and Brighton Diggins, and were considered a team with talent aplenty.

McHale loved the thought of trying to prove the old adage that a champion team would always beat a team of champions.

To help consolidate this changing of the guard, McHale's long-held belief that a mid-season interstate trip was the stuff that could build premierships (it had happened in 1927 when 'the Machine' travelled to Perth) would see the Magpies embark on a trip to Brisbane, Newcastle and Sydney in 1935.

But this time, South Melbourne - the team that had beaten Collingwood in the 1934 first semi-final- would accompany them.

The teams were 1-1 from their two home-and-away matches during the 1935 season. Collingwood had beaten South Melbourne in Round 1 and then just before the teams left for their interstate trip, the Swans defeated the Magpies by 53 points - with Pratt kicking as many goals as the opposition did, with 10.

The three 'friendly' matches on tour went ahead, despite some social activities on the night before the games, some of them involving a few drinking sessions - Collingwood won the first game in Brisbane by 32 points, the second, in Newcastle by three points; while South Melbourne won the game in Sydney by four goals.

Percy Bowyer recalled years later: "We beat them (in Brisbane). Len Murphy did all the damage. The night before we had been to a dance ... I had to help him up the stairs (on his return to the hotel). Then we came down to Newcastle and 'Leeter' (Albert Collier) had a night out. He didn't feel too good and McHale gave me his spot in the ruck. From then on, I was ruck-rover. Then, we went to Sydney and that was the only game where there was a prize for the winning team. It was an Akubra hat, a prized possession. They (South Melbourne) got their Akubras and we were not happy."

A much bigger prize, however, awaited Collingwood later in the year, though the task was made harder by a loss to South Melbourne in the Second Semi-Final before a Preliminary Final win over Richmond set up a return clash against the Swans in the Grand Final.

Fittingly, the 1935 Grand Final came 39 years to the day since the teams played in the 1896 Grand Final, in what was Collingwood's first flag, albeit in the VFA.

But there was a sensation on the Thursday afternoon before the game - one that would shape the contest.

South's best player, Bob Pratt, had been getting off a tram on High St, Prahran, two days out from the '35 Grand Final when he was struck by a tram. He suffered injuries to both legs and a badly bruised finger.

Collier was unaware of the incident when he was walking the streets of Collingwood. He said: "I remember coming home from work and going up along Hoddle St, and someone said to me: ' How are you going, Harry?' I said, "We will win if there is no Pratt', and (I didn't know) bloody 'Pratty' got knocked down.”

Pratt's bizarre incident gave rise to rumours that a betting syndicate might have been responsible. In a television documentary to celebrate the century of the league in 1996, the South Melbourne player suggested notorious Melbourne gangster 'Squizzy' Taylor was rumoured to have been involved.

Taylor wasn't. He had been dead for nine years, having been gunned down by 'Snowy' Cutmore in 1927, less than a month after 'The Machine' had won the first of their four successive flags.

The truth was far more straight-forward. The truck driver was, in fact, a South Melbourne supporter, C.T. Peters, who was so upset by the accident that he went around to Pratt's home that night to give him a packet of cigarettes as consolation.

With Pratt missing, Collingwood believed it could overcome South Melbourne. And that's the way it panned out. The Swans dominated the first term, but kicked 3.6 to open a 15-point lead at quarter-time. The second term saw the Magpies take a 10-point buffer into half-time.

A stalemate existed for much of the third term, as Collingwood fought hard to maintain a 12-point lead at the last change.

South Melbourne kept coming, but fittingly first-year skipper Harry Collier kicked a late goal to help win the match, with the final margin being 20 points.

In the victorious rooms, Collingwood president Harry Curtis declared it was: "the greatest premiership the club has yet won ... We had a young team to be remodelled for this and other premierships in the future, and our plans have so far been successful."

The celebrations at Victoria Park included a piano being wheeled into the middle of the ground, and on the following night, Harry Collier crashed into the front gate of Catholic Archbishop Dr Daniel Mannix's house in nearby Kew after a night of merriment.

But Collingwood's chances of winning back-to-back premierships looked to be in grave doubt in 1936 when the Magpies lost one of their champions, Gordon Coventry, who was cruelly suspended for the entire finals series after a match against Richmond.

Coventry was a scrupulously fair footballer who had never been reported before. He had been involved in the incident with Richmond's Joe Murdoch after boils on the back of his neck had been targeted. For the one time in his life, Coventry retaliated - and he and Collingwood looked to have paid the price.

When the eight-game suspension was flashed on the screens at theatres in Collingwood, there was widespread anger and condemnation.

But the Magpies had reason to remain optimistic. They would beat South Melbourne in the second semi-final - without Coventry - and the combination of Alby Pannam and Ron Todd in attack was looming as dangerous for the opposition.

Todd took over where Coventry left off and kicked four goals in the 1936 Grand Final, while Alby Pannam - whose father (Charlie Pannam Sr.) had played in the 1896, 1902 and 1903 flags, whose brother (Charlie Pannam Jr.) had played in the 1917 and 1919 flags, and whose nephews (Lou and Ron Richards) would play in the 1953 flag - would top score for the game with five goals.

Pratt, at the other end, finished the game with only three goals after being reasonably well held.

Both teams kicked three goals in the first term, with Collingwood two points ahead at the first change.

The Magpies dominated the second term to open a solid lead, but it could have been so much more. They kicked 4.10 for the term to the Swans' 2.3, leading by 21 points at the long interval.

South Melbourne was always going to challenge, and it did in the third term, with the difference being only seven points as McHale urged his players on at three quarter-time. And at one stage in the last term the difference was one solitary point.

But it was Pannam who helped to secure the win - and Collingwood's 11th VFL flag - with the sealer (which was his fifth goal) late in the game. It was the club’s sixth flag in 10 seasons.

The margin was 11 points - with Collingwood's 11.23 (89) proving too good for South Melbourne's 10.18 (78).

President Harry Curtis brought about the biggest cheer in the rooms after the game when he announced John Wren had donated 100 pounds to the team, with 25 pounds for McHale and Harry Collier.

It was Collier's sixth and final flag. As Gordon Coventry watched on from the stands, his brother's replacement had more than done his job on the day, and for a second successive Grand Final.

That night there were more celebrations. This time the venue was the Northcote home of Harry Collier's mum. She hosted the celebrations, as one newspaper said, "to celebrate her son's (29th) birthday and the premiership."

It's a fair bet to suggest that no one went anywhere near Dr Mannix's gate that night.