Sometimes it's easy to forget just what a good footballer Murray Weideman was.

Today he is remembered for so many other things. As 'The Enforcer' who roughed up opponents and protected teammates. As the acting captain who took on and upstaged Ron Barassi and the seemingly unbeatable Demons in the Grand Final that came to be known as 'The Miracle of '58'. As the footballer who decided to make extra dollars as a professional wrestler while still in his prime. As a figure so hated by other club supporters that he received death threats and was once the victim of gun shots being fired through his shop window. And as the coach of Collingwood's first ever wooden spoon team.

These are all elements of the larger-than-life Murray Weideman legend. And they're all true. But they tell only part of the full footballing story of the man known as 'The Weed'.

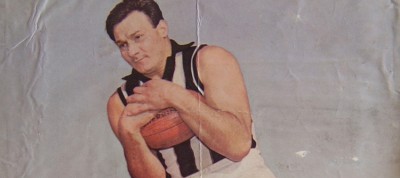

For underpinning everything that Weideman achieved is the fact that he was an outstanding footballer. He won three Copeland Trophies, the first of them at age 21, three club leading goalkicker awards and played for Victoria. He played in a Premiership at 17 and was full-time captain at Collingwood by 24. As a centre half-forward he was a matchwinner: a magnificent mark and splendid long kick who averaged nearly 1.5 goals per game throughout his 11-year career, but who was also expert at bringing other players into the game. He was a focal point in the forward line, or sometimes in the ruck, and threw everything into each game in search of a Magpie victory.

"He's one of Collingwood's 'big guns'," wrote Kevin Hogan in the Sunin 1958. "He's big, strong and capable of winning a game off his own boot, or turning the trend of a game with a few towering marks and long, straight kicks. Hands out some very heavy knocks, too, and most opponents keep a very wary eye on him."

Weideman was also an inspirational leader who lifted his teammates vocally, as well as through the personal example he set with his highly physical approach to the game. He handed it out and never complained when he copped it back. And he copped a lot more than he ever dished out.

Those qualities saw him elevated to the vice-captaincy in 1958, and the captaincy in 1960. So when regular skipper Frank Tuck missed the 1958 Grand Final through injury, it was the 22-year-old Weideman upon whom the leadership responsibilities that day were thrust. And boy, did he thrive on that challenge. Weed, Barry Harrison, Bill Serong and others gave their highly fancied Melbourne counterparts a physical hammering, then sat back and took care of things when the Demons sought retribution – all the while allowing Collingwood's talented and determined team of mudlarks to steal a game nobody thought they could win.

The Weed has dined out on his performance that day ever since. There are times when it feels like he almost beat the Demons single-handedly, so mythologised has his role in that game become. But the bottom line was that, as an acting captain at just 22, he had become – and remains – the youngest Premiership captain in Magpie history.

His game that day came to symbolise his career. After it, he was one of the biggest and in some ways most divisive figures in football. He was also one of the more misunderstood.

Weideman had never sought the 'Enforcer' tag that he ended up carrying. When he had arrived at Victoria Park for a trial in 1952, he was a skinny 16-year-old who was so lightly built that he was knocked back by the under-19s. But he was a desperately keen Magpie fan – despite having been born in Ballarat he'd moved to Fairfield with his family when just two – and he was determined to do everything he could to be a Collingwood player. So he returned to his local club Rivoli, playing with the under-16s in the mornings and the seniors in the afternoon, kicking bags of goals as a key forward. That grabbed selectors' attention, and the same group who had knocked him back in pre-season invited him back mid-year. He kicked six goals in just his second game, and the Pies knew they had found something.

The next year he completed the rare feat of being elevated through all three grades in one year, starting off in the under-19s, spending the next 12 weeks with the reserves (where he did well enough to win the best-and-fairest) and finally playing a handful of games – including the Premiership – with the seniors.

His game stagnated a little in 1954, but by 1955 he was a regular in the seniors and by 1956 he was a star. He had worked hard to develop his strength and fitness and, as he turned from boy to man, his physique filled out beautifully. But he was still seen as a relatively agile, high-marking, ball-playing forward.

Collingwood had always enjoyed a reputation as a team of 'hard' men, but by the mid-1950s many of the best had retired. So gradually, Weideman found himself being cast further and further into the role of the big guy who would bust open packs, dish out a few knocks and protect his smaller teammates. “No one came up and said ‘Murray, do you want the job?’," he said in 1991. "There was simply nobody else to do it.”

It might not have been a role he sought out, but it was one he ended up mastering. That mastery came at a cost, though, as he had to sacrifice much in his own game. "Taking on the role of protector dulled a lot of his own brilliant play," said former teammate Thorold Merrett. "But he filled that role perfectly, and he was prepared to give up so much of his natural game to do it. We all benefited from it, but Murray suffered.” Merrett said.

There were other costs, too. Opposition fans hated him, and subjected him to an unprecedented campaign of abuse and threats. In 1959 he needed police escorts to a game after threats on his life. He frequently received threatening letters and phone calls, bullets were once fired through his shop window, bricks thrown through his daughter’s bedroom window and bullets received through the post. But far from being cowed, Weideman seemed to grow larger amidst all the focus. He married a beauty queen, had a brief foray into professional wrestling (as 'Wild Man Weideman') and was a regular presence in newspapers and magazines. In the late 1950s and early '60s he was the biggest name at Collingwood and one of the biggest in the game.

He continued to play good football, winning Copelands in 1961 and 1962. But he was being plagued by a consistent back injury, and his weight was becoming something of an issue. So at the end of 1963, aged just 27, he decided to walk away from the game, being accorded a truly remarkable farewell, with thousands of children joining him in a lap of honour before each of his last two games.

He very nearly reneged on his retirement and returned in 1964, but Channel 9 wouldn't let him out of a contract he'd signed with them. Bob Rose always felt he would have won the '64 flag with Weed in his side.

He didn't spend long in the media, instead heading to first Albury and then West Adelaide. He eventually made it back to Victoria Park as coach in 1975 for what turned out to be two wild, tumultuous years. He fought with the president, Ern Clarke, and seemed to have trouble instilling discipline and professionalism into the playing group. The end result was the club's first ever wooden spoon in 1976, and an end to his VFL coaching career. His son, Mark, played 28 games for the club in the 1980s and for a while looked as if he could be as good as his old man, but his career was badly affected by injuries.

Murray Weideman will always remain one of the biggest figures in Collingwood history. Even those who never saw him play know much about his legend. His career – one of the finest and certainly most colourful of any Magpie, ever – has been justifiably lauded and will continue to be celebrated for generations to come.

- Michael Roberts