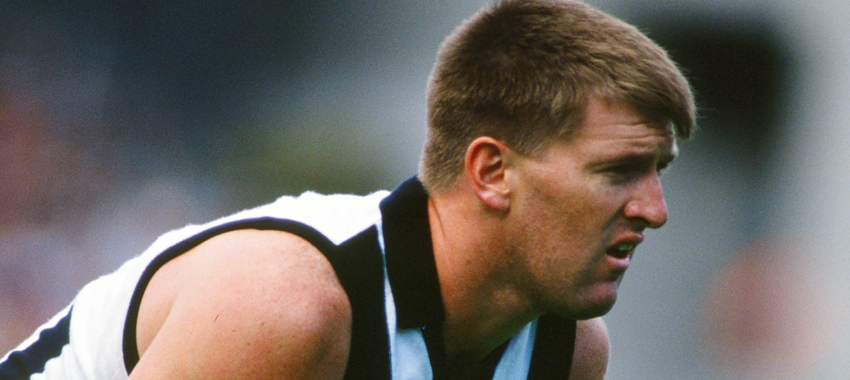

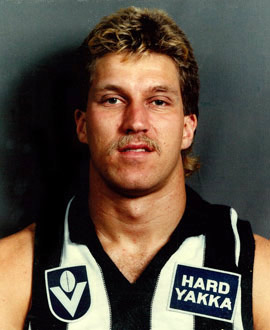

Few Collingwood footballers have extracted as much out of their natural abilities as Mick Gayfer, the club's ever-reliable, close-checking defender of the late 1980s and early 1990s.

That shouldn't been taken as a slight. Quite the contrary, it is a compliment of the highest order.

By his own admission, Gayfer wasn't blessed with the sharpest of skills, or the pure aesthetic talent others may have possessed. But he was a competitor, first and foremost, and he was a fitness fanatic who prepared himself - and his body - like few others in a time before full-time professionalism.

Combining his competitive edge and his fitness edge, he transformed himself into one of the most effective defensive stoppers of his time.

"I understand I was never the most naturally talented player, in terms of skills or speed or that sort of thing," he acknowledged. "I had to work pretty hard to get the most out of my career, so I'm pretty happy with everything I achieved."

Gayfer may not have won a trophy cabinet of awards, but he did win something more valuable - a premiership medal. And he won the absolute admiration of his teammates like few others.

Those who played with him loved him, even if his opponents didn't. And across eight seasons, his 142 games, and his solitary goal, Gayfer won the hearts of the Collingwood fans who backed him to the hilt, even if at times he gave them heartburn, and the close-checking cult hero was loved even more so because opposition fans had little time for him or his niggling tactics.

The Magpie players had a saying during the Leigh Matthews era, and it was perhaps a greater compliment than any of the individual award or honours on offer. Tony Shaw used it in his book, A Shaw Thing, published after the club's drought-breaking premiership in 1990. It was: "No one is safer than Micky Gayfer."

Shaw played on him just once, in a practice match at Victoria Park, but it was one time too many. He would recall: "He didn't have to, but he just tagged me. He was pulling my jumper, and I said: 'Get fair dinkum this isn't right'." All Gayfer did was to shoot back a big grin to his captain. The man who came to be known as 'the human blanket' had claimed another victim.

Gayfer had to do things the hard way to make it at VFL-AFL level. The eldest of eight children - seven sons and a daughter - he came from Rutherglen, not far from the Victoria-New South Wales border. For a time, he played with Corowa-Rutherglen in the now-defunct Coreen and District League, playing as a 15-year-old with the club's under 18's side.

Interestingly enough, that link with the other side of the Murray would come in handy in the years down the track, when he represented New South Wales in state of origin against what his home state of Victoria.

Gayfer attracted the attention of North Melbourne recruiting scouts after impressing with Caulfield, a VFA second division side, playing mainly as a centre half-back. Just a month after his 19th birthday, Gayfer was a member of the Kangaroos' under 19s premiership side and played eight games in the reserves the following season, before being delisted.

He returned to Caulfield, but fate, and a good Collingwood supporter, intervened to change his pathway.

He would recall: "North gave me the flick. In their opinion I couldn't make it, so I went back to Caulfield. My coach at Caulfield, Mick Robinson, is a mad keen Collingwood supporter and he rang them about me."

Gayfer had actually represented Collingwood in cricket before football. In his days with the Kangaroos, he spent two seasons with the Magpies seconds' side - fittingly as the backstop, the wicketkeeper.

He made his debut in a Collingwood jumper - wearing the No.51 jumper - against reigning premiers Essendon at Victoria Park in Round 1, 1986. He wouldn't miss a game that season, finding his niche in defence.

Lou Richards interviewed him in The Sun in 1986, saying: "Just look at the roll-call of big-name opponents who have been smothered by this quiet, unassuming country lad who looks more like a choirboy than a backline bogeyman. Tony Morwood, Mark Harvey, Richard Osborne and Michael Pickering have been covered effectively ... even Bulldog champion Doug Hawkins was stitched up after half time when Gayfer was swung to the wing."

In his second season, the club thought so much of him - as a player but just as critically as a person - he moved to the No.3 jumper. But stress fractures restricted him to only 13 games.

He kicked his only goal in his 44th game, against Fitzroy, at Princes Park, in round 15, 1988. He wouldn't kick another in almost 100 subsequent games, but more importantly, he saved plenty.

Gayfer played on some of the game's biggest players, including Jason Dunstall and Tony Lockett, but could just as easily adapt on smaller forwards, always happy to play his role for the team.

His niggling tactics, pulling of opponents' jumpers and capacity to annoy the hell out of the opposition attracted more attention and criticism followed. In 1989, his fourth season, his role on Dunstall prompted Hawthorn's Dermott Brereton to pen a newspaper article, saying: "I couldn't believe how crude some of Gayfer's tactics were. At one stage you could see Jason's jumper being stretched and I was 100 metres away in the stand."

Collingwood reacted immediately in defending him, saying he had been singled out and unfairly victimised. Gayfer didn't worry about the criticism, saying: "I didn't think there was a real lot in it."

"It happens all over the field. I'm quite sure there's Hawthorn backs who do it ... to Peter Daicos. Forwards hang on, too, when you run out.

"If you're touching them, you know where they are and you know where the ball is, too. But that upsets a lot of people."

As he became more entrenched in the side, and more confident in his own ability, Gayfer understood that he could back his judgment against certain players, and developed a slightly more attacking style.

Still, he handballed more than he kicked the ball; and that was fine with the coach.

"My ability is to play close and concentrate," he said. "Over the last (few) years I've learned to run off them as well and get more kicks myself.

"You tend to just work players out. Some players you've got to man up really tight and play really close, and then some you've got to give a yard, be on the forward side and just keep between them and the ball."

His biggest reward came in 1990 when he played a critical role in Collingwood's premiership season. After missing the first round, he played every other game for the season, including the Grand Final.

A funny incident occurred at the Grand Final parade the day before the biggest game of his career. He was ready to head off on the motorcade when someone yelled out from the crowd: "Gayfer, you *%?&".

Annoyed, he turned around and he was confronted … by one of his brothers with a massive grin on his face.

In the 1990 Grand Final, Gayfer played on Tim Watson then kept Essendon's resting rovers quiet. Afterwards, he said proudly: "It's just a sensational feeling to work so hard as a group and have it come off is just great."

Hard work was the secret to his success; he would work tirelessly on his fitness. Teammates marvelled about how much he put into being the best he could be. He swam every day before training as part of it all.

He maintained his durability in 1991-92, but faced some issues with his body in 1993. He suffered a strained adductor in the second game of the year, had other injury problems and spent some time in the reserves.

And Mike Sheahan admitted at the time he was being targeted by the men in white, explaining that the "whistle-blowers are engaged in Operation Gayfer, with a crackdown on what have been classic Gayfer tactics."

But Sheahan also had undoubted admiration for the Magpie backman. He wrote: "The thing about Mickey Gayfer is that you know if your man gets a kick against him, it's a kick he's bloody well earned, and that's healthy for the game. We have champions because an elite group rises above all the obstacles put in their path by Gayfer."

The end for Gayfer came quickly, and unexpectedly, in the 1994 preseason, and in keeping with his career, his exit was overshadowed by the club's decision to sack club great Peter Daicos on the same day.

He was only 28. When he was called into a meeting at the club with Matthews one March afternoon, the decision to delist him had come as a complete shock. But as the media outlets focused on the Daicos dumping, Gayfer's departure didn't make the same sort of headlines.

His teammates responded in the only manner they knew how, most of them left training that night and called into Gayfer's home on the way home. He tried to put his name forward for the preseason draft, but he was overlooked. His time in the AFL was over, but not his time in football.

He played for a number of years in country and local levels - winning a flag with Tatura in 1995. And he even returned to Victoria Park as the team's runner and fitness assistant from 1998-2001.

Matthews, the man who had backed him throughout his career, but who had ultimately sack him, saw him go from a "very raw player" in the 1986 preseason into a Collingwood premiership player.

"He's a player who has played in a premiership side when most people thought that he would not make it," he said. "That's more a reward for his hard work and persistence rather than anything he was actually born with.

"You have to admire him. He's one of the most admired players ... for his determination and his ability to work hard."

That’s why Collingwood supporters loved him.