When Collingwood took on Essendon at Victoria Park early in 1954, John Coleman – possibly the greatest full-forward in the history of the game – was at the peak of his powers. He'd started the season in dazzling form, having kicked 19 goals in his first two games.

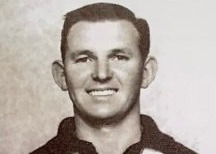

But Magpie full-back Jack Finck kept Coleman to just two goals that day, surviving a last quarter onslaught as the Bombers pushed unsuccessfully for victory and launched attack after attack. Finck, however, stood tall, and walked away knowing he'd beaten the best in the business.

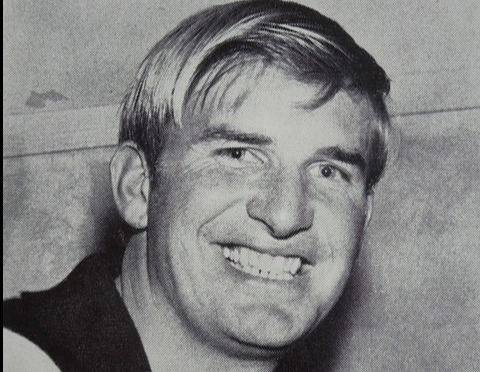

That performance cemented the 24-year-old Finck's growing reputation as the best full-back in the game. Remarkably, though, neither he nor Coleman would remain in the VFL for long. Coleman tragically suffered a career-ending knee injury just three weeks afterwards. And Jack Finck? He just walked away from it all a few months later and returned to a teaching job in the country.

Finck was born in Heathmere, about 20km north of Portland in south-west Victoria. Heathmere was a tiny town, and the football team's ground was actually a paddock on the Finck property (the shearing shed acted as changing rooms on match days). Jack’s father was a good country footballer, and Jack grew up with a footy in his hands. “I was always kicking it between the shafts of the dray, or between a couple of gum trees in the back yard,” he said in a 1991 interview.

Collingwood's recruiters came to Portland in 1949 to look at another player, but while there were tipped off about Jack, who had been winning a name for himself as a forward of some promise. Finck told the Pies he would be moving to Melbourne in 1950 to study teaching, and they issued an invitation to pre-season training.

He certainly attracted attention when he arrived at Victoria Park, partly for his skills and partly for his attire, which included an old army beret to keep the hair out of his eyes and a Melbourne jumper! After an early showing the Argus even likened him to Demons' great Don Cordner. "Jack Finck, the Portland boy, continues to impress and is a possibility for the full-forward job," it said. "He stands 6'1", weighs 12st and is fast and moves like a player."

He may have moved like a player but that didn't help him nail down a spot in the senior side. He spent 1950 with the seconds and managed a handful of senior games in 1951. He grabbed some big bags in the reserves, including a couple of seven-goal hauls and one extraordinary 12-goal game in 1952. But he never looked comfortable at senior level, even if he did finally manage to string some games together in the back half of 1952.

Then came two major turning points in Jack Finck's career. Firstly he finished his studies and took up a teaching appointment in Portland. Then he was moved into defence in the reserves, an experiment that was repeated in the seniors when Jack Hamilton injured his knee. Finck took to defensive duties as if he'd been playing there all his life, and did so well that when Hamilton returned from injury the selectors had to squeeze him into the forward line instead.

Finck was a revelation at full-back. The secret was that he used his experience as a forward to beat his opponents at their own games, using his uncanny judgement, anticipation and pace to beat his man to the ball. “I would try to disadvantage my opponent by standing between him and the ball, then rely on reading the play,” he said. “Once the ball was delivered I’d forget about him (the opponent) and go for the ball ... I just backed my judgement.”

Hec de Lacy, in theSporting Globe, described Finck’s game this way: “He plays full-back with the technique of a forward. Finck really plays along with the same anticipation as the opposition – until that psychological moment when the ball is driven to meet the spearhead’s lead. Then, with perfect timing, he anticipates the lead, beats the full-forward to the drop and clears. This modest Magpie plays the ball confidently with the certain knowledge that he has the ability to beat his opponent. He takes risks, but his sense of recovery, together with his anticipation and clean ball-handling, lessens the margin of error. Playing from in front like this, he clears with a dashing run that sends Collingwood into attack.”

It was a risky strategy for a full-back to adopt. But Finck carried it off beautifully, and by the end of 1954 his standing as a top full-back was beyond dispute, named in the Sporting Globe's team of the year and likened by some Collingwood officials and teammates to the legendary Jack Regan.

But this is where the teaching appointment back home kicked in. For those two glorious years when he was at the peak of his game, Jack had been commuting from Portland. Every Friday afternoon he would make the six-and-a-half hour drive down to Melbourne, arriving in town well after 10pm. He would play football with Collingwood on the Saturday, then turn around on Sunday morning and spend another six-and-a-half hours in the car driving back to Portland. Finck estimated he probably covered about 38,000 kilometres during his two years of commuting.

He first asked for a clearance in 1953 but Collingwood, to his surprise, refused. He tried again for 1954 but the club again refused. But by the end of 1954 Jack Finck had reallyhad enough of the travel and the frustrations of not training with his teammates – and this time Collingwood reluctantly cleared him back home. He was probably the best full-back in the game but, at just 24, his VFL career was over.

Instead he played at Heywood, where he won two League best and fairest awards, and later Edenhope, where he again won a competition best and fairest award and a few goalkicking titles. More importantly, he became a wonderful educator of young people (he eventually rose to be principal of Heywood High School), a passionate advocate for social justice and a deeply-respected community leader.

Still, later in life he admitted to some regrets at the footballing decisions he'd made. “Looking back I really don’t know how I did it,” Finck said. “I was completely and utterly exhausted by the end of the season. As a result, I don’t think I ever found out how effective I could have been as a League footballer. I do regret not having stayed on … not finding out what I could have been. I mean, I was 24 when I gave away League footy – how stupid is that?”

- Michael Roberts