By Glenn McFarlane:

Collingwood and Carlton played out a thrilling draw to open the VFL season on April 15, 1914 in a game best remembered for forward Dick Lee’s spectacular mark.

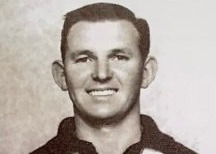

At the other end of the ground a young defender was described by the Argus as the “backbone” of his side in his best game in black and white. His name was Alan Cordner and he had been recruited from Geelong a year earlier. It was his 14th game of league football and his 11th with the Magpies.Exactly a year later, Cordner was dead. Due to the chaotic operations and misinformation of war, his family would not get official confirmation of his death for at least another year.

The passing of Joseph Alan Cordner was just a snapshot of the bigger picture where a significant slice of his generation was killed in World War One. Yet it was a deeply personal one for his family, from the western districts of Victoria, who had to deal with false leads, mistaken identity and possible sightings before hope was finally exhausted.

Cordner was a fine footballer who had played with Geelong for two seasons before crossing to Collingwood in 1913. He was a tall, nicely built defender with good aerial and kicking skills. Even after his first game there were signs that Geelong might come to regret letting him go, as his debut game with the Pies created "a distinctly favourable impression". He played in just about every position in his first year but eventually settled in defence, even filling in for Ted Rowell at full-back on occasions. After his first attempt at that role, Punch reported: With Teddy Rowell an absentee, Collingwood tried young Cordner between the uprights, the ex-Pivotonian doing everything that the veteran could have done. His kicking-in was classy, whilst his method of relieving his goal was up to approved standard."

He continued his improvement into 1914 and looked to have a promising future. But, according to Fallen, Footballers who never returned from war, written by Jim Main and David Allen, Cordner was the first VFL footballer to enlist on August 22, 1914. He signed up in the morning and played his last game in black and white colours that afternoon. It was his 23rd VFL game in total.

Soon after, the Herald recorded: “The executive of the Collingwood Football Club made a presentation to two of their players – A. Cordner and H. Mathieson (sic) – who have enrolled in the service with the Australian Expeditionary Force. (President) J. Sharp handed the men two gold wristlet watches, wishing them success and good luck.”

Cordner was a single man, employed by the Metropolitan Gas Works at the time and had been part of the school cadets at Hamilton College. His father Isaiah Joseph ‘Joe’ Cordner was listed as his next of kin.

In the club’s annual report of March 1915, it was noted that four Collingwood players and a committee member had enlisted and they were wished: “Good luck and safe return.”

Collingwood met Essendon in the first game of the 1915 season – on April 24 – and as the Magpies celebrated their good opening to the football year, Cordner was contemplating a very different challenge almost 15,000km from Victoria Park.

He had been “serving the colours” in Egypt, having embarked from Australia on the Hororata the previous October, and he and his mates from the 6th battalion were preparing to launch an attack on a stretch of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

On April 25, 1915, he would be one of at least six VFL footballers to be killed on the first day of the battle.

One of Cordner’s superiors wrote: “The casualty (Cordner), the informant, and two or three others got separated from their own men ... they were in the firing line about two miles from the beach. The informant was next to the casualty when he was shot. He tried to make the casualty speak and shook him, but could not move him from where he was. (The) informant really thought the casualty was dead, but admits that he may have been mistaken.”

The informant was not mistaken. But in a tragic twist, others were.

One nurse suggested she had been told that a man, possibly Cordner, had been repatriated from Gallipoli; there was even a report that he had been sent to England. Another suggested that he had been wounded and taken in by another battalion. The most fanciful had him returning to take part in the August offensive on German Officers’ Trench, some four months after he had gone missing.

All of these false reports were agonising to a family that wrote incessantly to the authorities pleading for news of their beloved son.

One letter from his father Isaiah, in July 1915, said: “I have not heard from my son ... since his arrival at the Dardanelles. As I have heard more than once from a second son who arrived after him, I am anxious.” Then, three months later: “Could you please let me know of his present whereabouts as no word has been received from him since 20th April last and if he was in hospital, he surely would have sent word.”

The cold, hard reality came the following year, long after the Anzacs had evacuated the Peninsula just before Christmas, and as the survivors of that Gallipoli hell were confronting even greater horrors in France.

Cordner was officially recorded as being killed in April 1916 – a year after it happened – with Sergeant Major Tutton writing to his parents: “I don’t think there is any reason to doubt that Cordner was lost on the first day at Anzac. The last time I saw him personally was charging over the hills some two miles inland about noon on 25th April. Some fellows say he was wounded and was seen going back to the beach, but one can’t rely on such statements.

He added: “Don’t place any reliance whatsoever (on the stories of survival). It is with the greatest regret that I can say that one must ... console oneself with thoughts of the gallant way in which he sacrificed his life.”

The Winner acknowledged how Collingwood wore “crepe arm bands” in a match in 1916 both in honour of Cordner’s passing and as a mark of respect over the loss of Lord Kitchener. The newspaper said in June 1916: “Originally hailing from Warrnambool, Alan Cordner first played with Geelong, but on coming to Melbourne joined the Collingwood club. He was a fine manly type of player, and on the outbreak of the war, was one of the first to enlist. Ever since the original landing at Gallipoli, he has been reported as missing but, as stated, his death was only officially reported on Saturday week. His two cousins, Dr H. Cordner, and Dr E.R Cordner, are both at the front.”

The Referee acknowledged that his club mates would never forget “the brilliant Collingwood player”, saying: “His sorrowing club-mates have hung an enlarged photograph of the dead soldier in the committee room."

Cordner’s school magazine, The Hamiltonian, paid a poignant tribute to him, saying: “His end, like the sacrifice of many others, is somewhat mysterious. There were so many heroes on that historic day, and we may be sure that Alan Cordner was such a one.

“The isolated heroics of that fateful day will never come to light and we cling to the knowledge that Alan Cordner was one of a small party who, penetrating four and a half miles inland, found themselves cut off by the Turks. Where better to leave him than on the hillsides of Gallipoli doing his duty “as a man is bound to do” who, fighting, fell that we for whom the death list bears no name, might live secure in the knowledge that the old school spirit reflected in ‘the old Parrot’ was not found wanting when the umpire sounded the whistle for the great game.”

The ‘old Parrot’ was just 11 days shy of his 25th birthday.