By: Glenn McFarlane

Peter McKenna recalls that John Greening’s self-assured approach to football and life was apparent from an early discussion the pair had.

The young Greening told the Magpie forward that he intended to pass Ted Whitten's then-VFL record of 321 games.

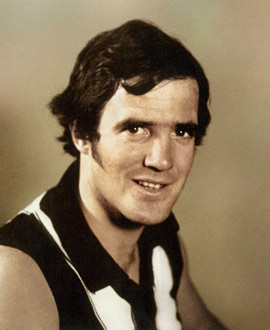

“John was convinced it was going to happen,” McKenna said. “He ended up being the most talented player that I played with.”

Greening went even further when speaking to the Herald Sun's Mike Sheahan many decades later, saying: "I was hoping to play 500 games at Collingwood. I wanted to be captain, coach, be there at the top of the tree, premierships forever and a day. (But) unfortunately I wasn’t born with eyes in the back of my head.”

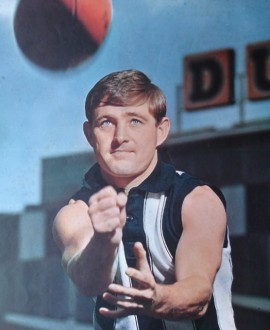

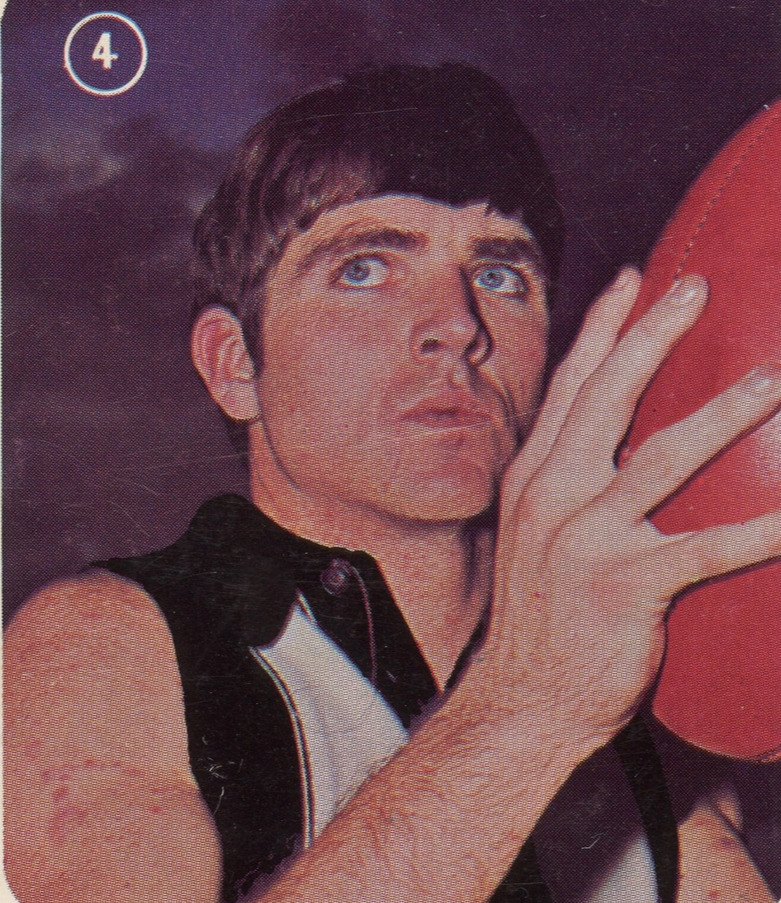

In the end, he would only make it to 107 games - the sublimely-skilled, perfectly balanced wingman-half forward who wore Bobby Rose's famed No.22 would be like a comet that flashed before us but would be gone from the game too soon.

It was July 8, 1972, and Collingwood's Round 14 clash with St Kilda at a muddy Moorabbin was meant to be a tough contest between two likely finalists.

Greening was 21. He was playing his 98th game. His 100th game was meant to be a fortnight later. Instead, it would take him a further 23 months - not to mention a life-threatening, life-changing battle - to reach those three figures.

To this day, he doesn't particularly like to talk about what became known as "the Greening Incident". He has spent more than half a lifetime trying to forget it.

Greening received Life Membership in December 2011.

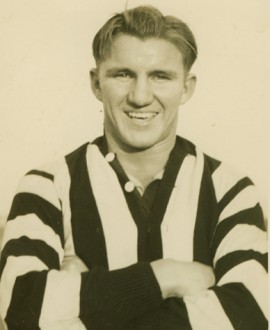

But he has never forgotten how the day started. His coach, Neil Mann, asked him for something special moments before running out, saying: "Have a good one, JG, we need you." Greening has already enjoyed a stunning start to 1972, his fifth senior season after debuting for the Magpies as a 17-year-old in Round 5, 1968.

The next thing that the one-time Tasmanian from Burnie knew - he had been signed by Collingwood as a 15-year-old - was waking with doctors and nurses surrounding him, telling him he was lucky to be alive.

He would recall: “I was only 21, not even at my peak … suddenly you wake up in hospital with someone thumping on your chest, saying you nearly died.”

Almost as soon as the game had started, Greening had taken a mark and kicked the ball long towards McKenna. Then the lights went out.

A sickening off-the-ball incident involving St Kilda's Jim O'Dea left him unconscious on the ground; with trainers frantically trying to tend to him but unable to do much; his worried teammates white-faced with uncertainly and anger.

From that moment on, it was more about Greening's welfare than what took place over the next four quarters, though Collingwood did win by five goals.

Greening was in a coma for more than 24 hours after suffering cerebral concussion; the blow cut oxygen to his brain for a period and there were fears for his life and wellbeing. Collingwood, the club and the community, united in its prayers for the young star to first pull through, and then to make a full recovery.

A young kid, not yet eight years of age, spent the best part of a week praying. The kid's name was Eddie McGuire.

Greening was honoured by the club in 2007 before its round 13 match against Hawthorn.

It was fitting that McGuire, as Collingwood president, would help bring about Greening's elevation as a life member and a Hall of Fame member on what proved to be emotional nights almost four decades later. Greening now lives on the Gold Coast, but he still says that black and white runs through his veins.

But those acknowledgements of what he achieved in his time in the game were deep into the future.

In the days, weeks and months after the incident, Greening was locked in a battle to survive and then to restore his life, more so than his footy career.

Collingwood laid a complaint with the VFL over the incident and sought police intervention. There were pleas for supporters to come forward to tell authorities what they had seen in the split second incident that so many in the crowd missed.

Within a fortnight, O'Dea was suspended for 10 weeks, a penalty that many at Collingwood felt was woefully inadequate. Greening's then wife filed a Supreme Court writ on the St Kilda player alleging assault, and on both him and the Saints seeking damages.

She dropped it after St Kilda and Collingwood agreed to set up an appeal for Greening and his young family, which ultimately raised around $50,000, and which was partly funded by a charity pre-season match between the two sides. Incredibly, O'Dea played in the match.

Greening spent almost six months in hospital and rehabilitation centres. He was still there when he finished only 11 votes adrift from his teammate Len Thompson in the 1972 Brownlow Medal, despite the fact that he missed the rest of the season.

That could so easily have been the end of the John Greening. The fact that it wasn't says much about the determination and desire of the man.

What started out with a social football match at Hurstbridge in October 1973, ended up in a memorable reserves match return in early 1974.

He was entered into Collingwood's Hall of Fame in early 2011.

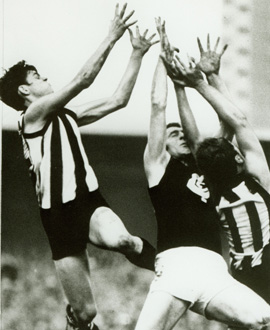

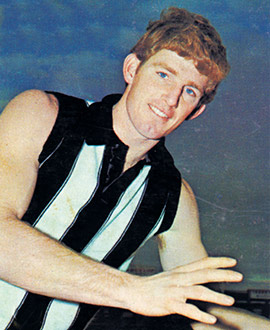

Then he was recalled to the Collingwood senior side for the Round 9 match against Richmond in 1974. He led the team out that day, was cheered on by the 66,829 fans at the MCG. In keeping with the moment, he kicked a goal with his first kick and finished with 24 disposals in the 69-point victory.

But as physically taxing as the comeback had been; the emotional and psychological one proved even tougher.

Greening would manage only nine games in his emotional comeback to football - three in 1974, two in 1975 and a further four in 1976. It brought an end to his time at Collingwood, though he was never forgotten by the people who had shouted loudest for him in the stands and terraces.

Those shouts have morphed into hushed tones over the past four decades about how good Greening had been before he had been so rudely - or crudely - interrupted.

That's what made it so hard.

Greening was nowhere near his peak - perhaps he wasn't even at base camp - when his VFL career was over.

But what has been rightly acknowledged at club functions Greening has attended in recent years is that as breathtakingly cruel as the events of that winter's day at Moorabbin may have been, we should appreciate what was, as much as what might have been.

Those not lucky enough to have been old enough to see play live, need only type his name into YouTube and those skills will unfold again in black and white.

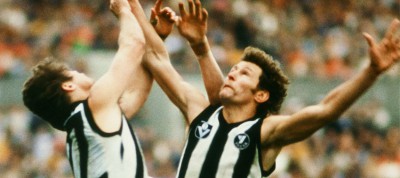

There's the freakish talent, the audacious speed, the exceptional ball-winning skills, his balance on either side of his body, his spring-heeled leaps, his uncanny sense of where the goals - and his teammates - were. He was a football gem who regularly seemed to make the impossible almost common place.

In many ways, Greening played football with a sort of freedom that defied boundaries or barriers.

His teammates have been superb in articulating that over the years.

The late Len Thompson compared him with two-time Brownlow Medal winner Robert Harvey; Wayne Richardson reckoned he was more like James Hird; while Peter McKenna and Barry Price maintained that he was the most exciting athlete that they had played with.

His late coach Bob Rose, with whom he shared the No.22, was insistent that Greening would have likely gone on to be one of the greatest players in the history of the game. It’s a fair assessment from a man well qualified to know.