By: Glenn McFarlane

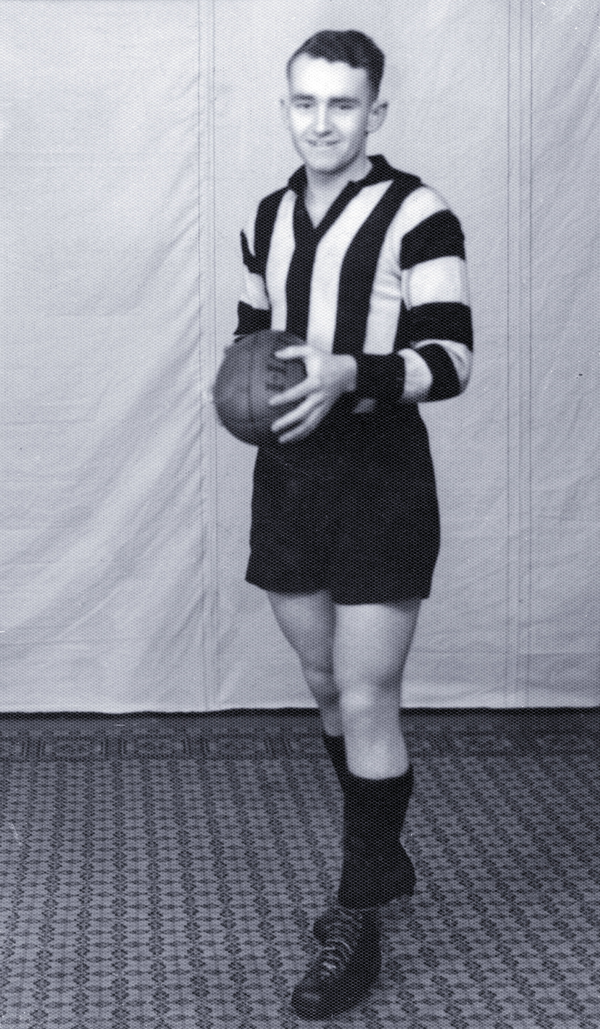

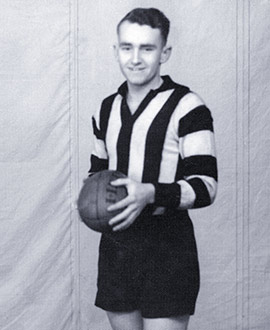

IT'S fair to say that no Collingwood footballer has ever made as rapid an impact on the field as teenage prodigy Des Fothergill.

Let's just look at his first four seasons in black and white. Two Copeland Trophies in his first two years - as a 17 and 18-year-old - in a side that was full of champions. And then a third Collingwood best-and-fairest award in his fourth year, 1940, in a season that would see him poll the equal most votes in the Brownlow Medal.

Fothergill was one of VFL's young sensations, and what happened in the Brownlow Medal count provided a sensation of its own.

After yet another outstanding year for the Magpies, the then-20-year-old polled 32 votes in the league's fairest and best award, which was five votes greater than any other previous winner had achieved.

The only problem was that another player also polled 32 votes, playing the same amount of games (18) and polling in the same amount of matches (14). He was South Melbourne's Herbie Matthews.

The Argus detailed: "When the votes of the central umpires in each game were counted, the permit committee of the league last night found that Matthews and Fothergill had each been allocated 32 votes. Members of the committee were in a dilemma concerning the position, which had not occurred since rhe medal was first awarded in 1924. In 1930 there was a tie between S Judkins and H Collier (there was no mention of Allan Hopkins), but the medal was awarded to Judkins on the number of games played."

Both players gained seven best afields, four two-vote games, and three one-vote games.

The football public had no issue with the umpires' verdict, with the Australasian stating: "Public opinion is generally right and the almost unanimous vote of football enthusiasts will place Herbert Matthews, the South Melbourne captain, and Des Fothergill, the Collingwood rover, as the outstanding players for 1940."

It was a fitting result, but hardly the fitting reward for each of the men.

Fothergill and Matthews could not be separated in any form of countback, which presented the VFL with a dilemma given that its rules stipulated that only one winner could receive the Brownlow Medal.

One newspaper said: "All the tests were applied in order to decide between the two leaders without avail, and now the league will have to decide. It is probable that each will receive a medal. Each is a very fine exponent of the game and also a splendid all-round athlete."

The only problem was that the VFL decided to stick to the original lettering of the rules surrounding the medal - there could only one winner, not two.

Fothergill and Matthews were listed as joint winners, but the league decided to keep the original Brownlow Medal and struck two cheaper, replica medals for the pair.

It wasn't until 1989 that the league got the chance to right the wrong of almost 50 years earlier, when it presented both players with new Brownlow Medals.

On the night Fothergill took along his replica, and rejoiced when he got hold of his Brownlow Medal. He told Channel Seven: "It's very pleasing. I've had the replica for about 49 years, so it is good to get a new one."

Unfortunately for Collingwood, Fothergill took up an offer from VFA club Williamstown the following season, and would be lost to the Magpies until 1945. He spent one year in the VFA before serving in the Second World War before making an emotional homecoming to Victoria Park in the last year of the war.

He was still a very good player, though a knee injury dulled some of his impact.

Fothergill had to be replaced at half-time in his last game, in Round 12 game against Fitzroy in 1947 after "playing as though he were nervous about the condition of his knee ... the opinion was expressed that he might not play again." The Collingwood comet was gone, after only 111 games, and just 10 days before his 27th birthday. But his links with the Brownlow Medal would remain.