Sam Campbell didn’t die in battle. In fact, he never even made it to war.

He died in a place unimaginably far removed from his homeland, let alone from the battle front, and tragically in the dying days of a war that he would lose his life to, but never get to witness.

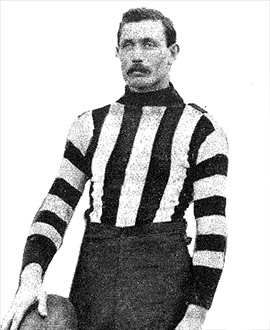

Campbell remains one of the saddest stories of Collingwood’s sacrifice to war. He was 27 years old when he enlisted in May 1918, even though he marked down his age by a year for the paperwork. By that stage, he had long since been a Collingwood footballer. That experience in black and white had been so brief that it barely rated a mention despite the fact his one and only game had come in a Collingwood-Carlton clash eight years before he enlisted.

Campbell had been born in Ballarat on March 12, 1891, exactly 11 months before the civic meeting at the Collingwood Town Hall that gave birth to the football club that he would come to represent. He was from a large family – he had seven siblings – which eventually came to make their home in the tough inner suburbs of the city.

He came under the Magpies’ notice as a teenager with Spensely Street Methodists (also known as the Clifton Hill Methodists), and impressed in the try-outs ahead of the 1910 season. In the lead-up to Round 1, the Argus said: “The (Collingwood) committee has some splendid juniors … to replace (some of the senior players who had departed). The new men most likely to earn the right to join the Magpies nest (include) Campbell (forward), from Spensely Street Methodists.”

Circumstances worked out for the 19-year-old hopeful as the Magpies were missing a few players heading into that Round 1 game against Carlton at Princes Park. He played forward but did not trouble the scorers, and the Blues ran out 28-point winners. It was his one chance at Collingwood, and he would never again wear the black and jumper in a senior game.

The next time Campbell’s name would come to note was when he decided to enlist in the latter stages of the war. At that time no one knew how long the war would continue.

The clerk had previously been rejected by the AIF because of a nasty appendix scar that was noted in his medical files. But by May, 1918, doctors had allowed him to join the 12th General Service Reinforcements. His parents were dead and he listed his sister, Miss Elsie Campbell, of Alphington, as his next of kin.

He probably realised the war was rushing towards a climax when he boarded the Barambah on August 31, 1918 – just as news of critical new battles involving the Australians in France were filtering back to Melbourne. What he couldn’t have known is that the ship he was travelling to England on would play a role in his demise. And he could never have imagined how the conditions of that ship would months later become the subject of intense discussion and debate in the House of Representatives.

The voyage was relatively calm until the ship called at Cape Town, South Africa. Soon after, a serious influenza crisis broke out on board and it soon became a very dangerous vessel to be on. Hundreds of soldiers were afflicted. Almost a dozen died at sea. As the ship made its way up the West African coast, a stop was designated for Freetown, Sierra Leone, to unload some of the most severe cases. Six of them, including Campbell, died soon after they were brought ashore.

Campbell had taken ill on October 11, 1918 –exactly a month before the Armistice was signed – and was listed as having influenza four days later. Gravely ill, he was taken ashore along with a number of others to the Tower Hill Military Hospital. He died there the next day, on October 21, with pneumonia combining with influenza to bring a sudden end. The war was over 21 days later.

A note sent back from Major Cordner informed: “Private S. Campbell was admitted to the Military Hospital, at Tower Hill, from HMT Barambah suffering from influenza and pneumonia. He was at the time in an extremely critical condition. He was admitted on the afternoon of the 20-10-18 and died the following day. He was buried at the Military Cemetery, King Tom, Freetown, Sierra Leone."

Because he had not actually died in battle, in the eyes of some, there was a differentiation between Campbell’s death and those who had perished at the front. When the Argus came to report his death, they listed all the men who died in battle first, then listed Campbell and others among those who “died of other causes”. Alongside Campbell’s name was the information “Cause not known:” At least he was included on Australia’s Roll of Honour, as being one of the soldiers claimed by the war.

Later, his effects were sent back to his heartbroken sister. They included a compass, a damaged wrist watch, a wallet, five keys on a ring, a belt, a diary and some photos – not much from a life cut so short.

- Glenn McFarlane