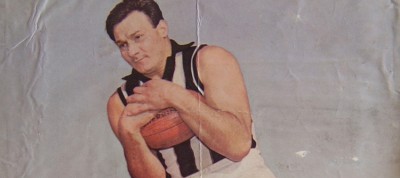

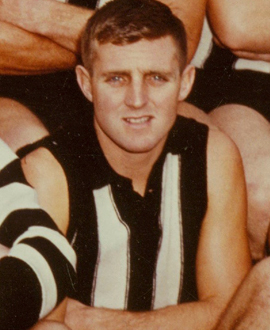

The day a young Ron Reeves stood his ground and marked in the path of a runaway draught-horse was the day destiny reserved a senior black and white guernsey for his back.

It was during one of those rugged games of street footy that kids used to play in the back blocks of Collingwood. One day, having flown for a mark and with the leather nestled safely into his small hands, he suddenly heard his mates screaming. He looked up and saw a huge draught horse bearing down on him. He turned and ran – but not fast enough. Ron was knocked out, and so were many of his teeth. He also suffered a broken collarbone and two broken ribs.

When Ron’s father emerged from the house, he saw his boy lying battered, bruised, broken and bleeding on the footpath, his Collingwood jumper covered in blood. But amazingly, Ron still had hold of the football — not even a bolting horse had been enough to make him let go! At that point, Ron’s father knew his boy would one day play for Collingwood.

Ron Reeves was one of the dwindling number of Collingwood recruits born and bred locally. The Reeves family home lay close to the border with the Richmond municipality, and many were the street fights that would break out whenever the two sides met. “I can assure you I took some tough knocks for Collingwood long before I ever pulled on a boot for them,” he once said.

Ron’s earliest football was played at the Lithgow Street State School, of which Lou Richards was also a former pupil. From there Reeves graduated to Richmond Tech, where he captained the school football team. At the same time he also played with local junior club called the Richmond Scouts. He then spent a year with the St John’s Young Catholic Workers side in East Melbourne. The Magpies had been following his progress since his days with Richmond Scouts and brought him across to play with the under-19s in 1956.

Reeves played mainly as a rover or a wingman in that first season. In 1957 he graduated to the reserves, where he played a few games in the centre but spent most of his time in the back pocket. His performances there were so good that he won the reserves’ best and fairest award. More importantly, he was rewarded with his first taste of senior football, given a spot on the bench in the last game of the year (unfortunately, his debut came on his sister’s wedding day!).

He kicked a goal that day (one of only two he would kick in his 122-game career), but began the next season back in the seconds. When regular back pocket player Lerrel Sharp and possible replacement Bob Greve both suffered injuries which forced them out of the round eight clash with South Melbourne, Reeves found himself included for his first full senior game – lining up against future AFL Legend Bobby Skilton.

Despite some early hiccups, in the end he had a superb game and looked quite at ease in League ranks. The Sun named him as Collingwood’s second best player and described his game as “a dream debut”, while The Sporting Globe said he “cleared with the confidence of a veteran”.

From that moment, the back pocket position was his. He held his place for the rest of the year, even when Sharp and Greve returned from injury. His performances in the home and away matches were strong and consistent, but it was his efforts in the finals that season which really earmarked him as an emerging star. The second semi-final was just his 11th full game of VFL football, but he handled the pressure with a maturity which belied both his years and his inexperience.

Reeves had been named among Collingwood’s best players in its first two finals, but his performance in the Grand Final was even better (after he’d taken himself off to the mountains for a spot of fishing the day before the game to calm his nerves). After his third great game in as many weeks, The Sun was already proclaiming him a Collingwood hero.

Throughout 1959 and 1960 Ron Reeves was generally acknowledged as the best back pocket player in the League, and won interstate selection in both years. In 1959 he also cemented his reputation as a superb big-occasion player when he won a golf bag as Collingwood’s best player in its only finals appearance.

Reeves brought an aggressive and attacking approach to a position usually marked by conservatism. He liked nothing better than to run up the ground, either to meet the ball and make a clearing dash followed by a long kick or to take a handball from one of his half backs. This was considered adventurous play in those days, but rarely were his assessments of the risks involved proven to be wrong. He was also a magnificent mark for his size.

His reading of the game and his anticipation were also important factors in Reeves’ success. He was quite fast, but still relied on speed of thought rather than speed of foot to give him the break on his opponent. At 175cm (5ft 9in) and a sturdy 76kg (12 stone) he was ideally built for the position, and durable enough to miss few games through injury. His bustling, busy style of play won him praise from many quarters, not least from the man alongside whom he played for several years, Harry Sullivan. “He was a fantastic player,” said Sullivan years later. “He was the best mark for his size I have seen, but he also knew when to spoil and when to smother. I could leave the goal square with confidence because I knew he would get anything that went over my head. And he read the game so well! In my view he was the complete back pocket player.”

Reeves and Sullivan formed a superb combination in the last line of defence for Collingwood in the late fifties/early sixties, and it is perhaps not surprising that Reeves’ best football was played during that period. Sullivan retired after the 1960 season, and though Reeves continued to be one of Collingwood’s most consistent performers he did not quite recapture the form of his first few years. Five games into the 1965 season he was dropped to the reserves and chose not to play on.

In retirement he concentrated on his other great love, fly-fishing. Later he took up tournament accuracy casting, where competitors use spinning or fly-fishing gear to hit selected targets over various distances. He captained the Australian team in five world championships, and won three Commonwealth gold medals.

In his years in the back pocket for Collingwood, Ron Reeves won many plaudits. He brought a sense of adventure to the last line of defence, and showed that back pockets could be more than just the nuggety, close-checking types that so often filled the position.

- Michael Roberts