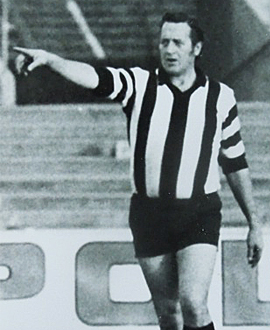

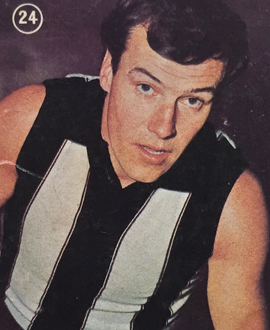

In the early 1970s, Peter McKenna was the biggest name in football – and probably the most popular the game had ever seen. This was true pop-star hysteria hitting the Victorian Football League. Young girls would run onto the ground to kiss him before the start of matches. The club was so heavily inundated with requests for photos that they had to print off thousands of them with a pre-prepared signature. He released an autobiography – as only a few others had done before him – produced a couple of pop records that were played on radio, and had a short-lived role co-starring on a Saturday morning TV variety show. It was 'McKenna Mania'.

All of which makes it even more remarkable to recall that, just a few years earlier, many of those same fans who idolised him had been calling for McKenna's dumping.

When recounting Peter McKenna's career story, many people point to his 12-goal game in the opening round of the 1966 season against Hawthorn as the turning point. But it wasn't: the goals dried up from the very next week and he was out of the side a few weeks later, dropped to the reserves for the rest of the season after refusing to accept a Collingwood directive not to play in mid-week Teachers College games. Instead it was a much lower-profile performance against South Melbourne two years on that saved a career that was very much at the crossroads.

In this way, among others, McKenna was very much like the only man who has kicked more goals in a Collingwood jumper than he has – Gordon Coventry. 'Nuts' arrived at Victoria Park late in 1920 but didn't 'click' in VFL football until midway through 1925. McKenna's career wasn't quite as slow a burn but it was close: he'd played three-and-a-half full seasons of football before really finding his feet.

He had arrived from West Heidelberg YCW in 1965, following a junior career dominated mostly by soccer. His first two seasons were unremarkable, save for two wonderful performances against Hawthorn – five goals in just his third game in 1965, and the even dozen in 1966's opening round. The return in 1967 was reasonable (47 goals from 16 games) but he struggled again in '68, missing games through suspension and then being dropped after kicking only four goals in three games. The critics thought him too slow and too fond of playing from behind. He'd even been tried at centre half-back in the seconds. When he was recalled for the Round 9 clash with South Melbourne, Lou Richards summed up the prevailing mood when he branded McKenna as 'hopeless'. But Lou was left with egg on his face when Peter kicked six that day, six again two weeks later against North Melbourne, then six more against Richmond and seven against Fitzroy. He finished the season with a bag of 11 in the return bout against South. Peter McKenna, goalscoring machine, had arrived.

The records that flowed from that point on were phenomenal. He kicked 98 goals in 1969, a staggering 143 in 1970 (still the best ever by a Collingwood player), 134 in 1971, 130 in 1972 and 86 in 1973. He finished his Magpie career with 838 goals from 180 games – an average of 4.65 goals per game, significantly better than Coventry's 4.24. He won the Copeland in 1970, topped Collingwood’s goalkicking list eight times and the VFL table twice. He set a new League mark of 13 double-figure hauls (his highest was 16 against South Melbourne in 1969) and also kicked at least one goal in 120 consecutive appearances between 1968 and 1974 – a remarkable record that still stands as a testament to his extraordinary consistency.

Although the results were jaw-dropping the strategy behind them was simple. McKenna's game was built on three core components. The first was a wonderful understanding of the game that allowed him to turn a healthy, though not blinding, turn of speed into consistently damaging leads. The second was an almost telepathic understanding with his midfielders: he knew when and where to run, and they knew where to put the ball. And the third was a laser-like right boot: his drop punt kicking was a thing of beauty and he rarely missed from inside 50 metres, no matter how tight the angle. He was more than handy with snapshots, too, but his bread and butter was the lightning lead, safe mark and deadly drop punt. Even today, when goalkicking remains a problematic part of the game, McKenna's is the name regularly invoked by supporters as the gold standard of the art.

McKenna, one of the most modest champions the game has known, has always been quick to pay tribute to work of his teammates upfield. “I had an understanding with the Richardson brothers and Barry Price that was absolutely uncanny, and quite unplanned,” he said after he retired. “When they got the ball I just knew instinctively where to lead, and they seemed to know where to kick it. And they made it easy; their kicking was so good that there was no way you could miss it unless it bounced off your chest.”

As the goals flowed, so did the adulation. Every kid sporting a Collingwood jumper to the matches, or in suburban streets, seemed to have a white glossy plastic square bearing a black number “6” on the back. He was more than just popular: instead he was accorded a kind of hero worship and adulation that has been rarely, if ever, seen in our game before or since. He was footy's first true pop star. If Twitter had been around in the early 1970s, he might have broken the Internet.

The young girls running onto the ground for a pre-match peck on the cheek became a regular event. One particularly wet day at Victoria Park, a girl jumped the fence and offered him her umbrella. The records sold well (though McKenna still claims self-deprecatingly that most of them sat in his mum's garage or the bargain bins at Coles), even if the pop style was less his thing than Irish folk ballads like Galway Bay, which was his go-to song at club functions. About the only thing that didn't work was his foray into TV, where the Saturday morning time slot proved an insurmountable problem. Still, he was replaced by a stuffed pink ostrich and 'Hey Hey It's Saturday' seemed to do OK without him.

The thing that's often overlooked when analysing McKenna's popularity is how hard he worked to look after those fans who idolised him. In those days a school teacher by profession, he took great pleasure in fostering his massive following among youngsters. He frequently appeared at functions and clinics conducted by junior clubs, and went out of his way to personally answer fans' letters, sign autographs, talk to them at schools and in parks, even have a kick with them in the street. Once he even got into trouble for attending a child’s birthday party on the eve of a big game!

What makes McKenna's generosity of spirit even more remarkable is that it existed in the face of unimaginable family tragedy. Late in 1967 he lost his 23-year-old sister, Marie, to an epileptic seizure. Incredibly, he went out and played for Collingwood that afternoon (the heartfelt handshake he received that day from fierce rival Wes Lofts has stayed with him ever since). His father, Kevin, died of diabetes-related causes soon after the 1970 Grand Final. Then his brother, Gerard, also a diabetic, drowned during a diabetic seizure. He was only 29.

Through it all, Peter kept kicking goals – and presenting the smiling, good natured public face that had helped make him the most marketable footballer of his generation. He was shattered when dropped for a 16-year-old Rene Kink in the 1973 preliminary final (a moment he still ranks alongside the 1970 Grand Final as the greatest disappointments of his career), but his Collingwood career didn't end until he suffered a serious kidney injury playing in the reserves in 1975. He spent 1976 in Tasmania, playing footy with a protective guard, and looked likely to return in 1977 until a pay dispute forced him to reluctantly accept a better offer from Carlton. He kicked 36 goals in 11 games there before retiring at the end of 1977 – largely because he couldn't stand the thought of having to play against Collingwood again. He then headed to the VFA with Port Melbourne and Geelong West. After that he became a much-loved commentator on Channel 7, his partnership with Don Scott on the Sunday Army Reserve Cup matches attracting a cult following.

In 1999 he was inducted into the AFL's Hall of Fame, and his speech that night reminded everyone of the warmth, humility and gentle good humour that has made him one of the most loved people within the football industry. And in 2010, he finally got his reward when he was asked to present Nick Maxwell with the Premiership cup. McKenna later described it as his most treasured moment in football. As a man who gave so much pleasure to so many Magpie fans, nobody had done more to deserve the chance to stand on the dais with Premiership cup in hand. Peter McKenna's football journey was complete.

- Michael Roberts