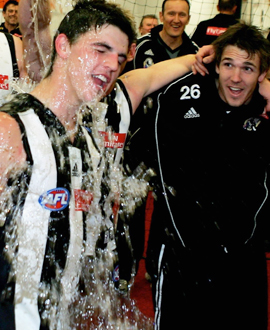

If you had to choose one game to explain what Paul Licuria meant to the Collingwood Football Club, it would be impossible to go past a memorable September night in Adelaide in 2002.

It came in the Magpies' qualifying final against Port Adelaide, at the old Football Park, when he helped orchestrate one of the biggest upsets in finals history. In a game against the minor premier, and in the absence of Collingwood's injured skipper Nathan Buckley, Licuria turned in a masterclass performance.

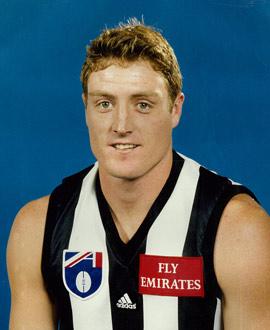

As the reigning Copeland Trophy winner, and well on his way to a second, he was already valued immensely by his teammates and the Magpies' faithful. But his performance in his first final that night left any impartial observers in little doubt as to his role as the heart and soul of that Collingwood team.

Licuria had always had a rare capacity to find the ball (he had more than 450 disposals in seven consecutive seasons), and he found plenty of it that night, having a career-best 40 disposals. But he also shut down Josh Francou, whose form had been so good he would finish runner-up in the Brownlow Medal.

So that was Licca in a nutshell: doing the team thing, a shut down job, to the absolute best of his ability, and then somehow adding to that his innate ability to get plenty of the ball as well. By the end of 2002, everyone inside and outside Collingwood recognised that Paul Licuria was an elite footballer.

His disposal efficiency wasn’t his strength in his early years, but he painstakingly worked on making it an asset, not a weakness. His pressure was elite; his tackling ferocious. He was, by his own confession, not the most gifted of players. But he worked harder than most, and through sheer hard work and a fierce determination, he built a tank that produced a capacity to keep running when others couldn't.

Above all, he was selfless, always doing things for the sake of the side rather than for his own benefit, and aiming wherever possible to improve those around him.

"If we all had a set of values to live by, Paul Licuria would be a ten out of ten," Buckley told Champions of Collingwood. "There was a little bit of self doubt early and question marks about whether he was good enough, but through sheer will and hard work, he created a mindset that underpinned the way he went about things. Once he had that belief system ... there was absolutely no stopping him."

Licuria had grown up as a Collingwood supporter, playing for Keon Park Stars. In a different age, he would have been residentially zoned to Collingwood, but in the drafting era, he was snapped up by Sydney as pick 24 in the 1995 national draft. He had to endure a knee re-construction at the age of 16 in 1994 and then had the other knee reconstructed just before the 1995 draft.

After 10 games in three seasons with the Swans, he was traded to Collingwood ahead of the 1999 season, playing 13 games that first year and earning a Rising Star nomination.

He was mostly regarded as a defensive player in those days: a dogged, determined type with a big engine who would do a tagging job on an opposition star. But in his third season - 2001 - Licuria took his game to a higher plain. He played every match and surprised many outside the club when he won the Copeland Trophy, knocking off Buckley, drawing some criticism from the likes of Mike Sheahan, who damned him with faint praise by describing him as an "honest toiler".

No one was saying that a year later, after his extraordinary finals performance against the Power, and winning a second consecutive Copeland Trophy. He also won the coveted Bob Rose Award for the best player in our finals series. He wasn't simply stopping players anymore, as he did with the likes of Jason Akermanis and Andrew McLeod, he was also hurting them back the other way.

His teammates loved his commitment to the tasks set for him, and the wholehearted way he approached every game, and every contest. The fans, many of whom were initially critical, did too. By the early noughties he had become one of the club's most popular players.

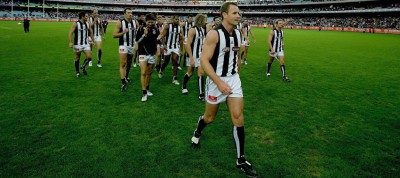

Licuria wasn't afraid to show how much it all meant to him. The image of him, arm-in-arm with Mick Malthouse, crying uncontrollably after the 2002 Grand Final loss remains one of the rawest images in Australian football.

He was a member of the club's losing Grand Final side in 2003, too, finishing fourth in the best-and-fairest that year while winning best clubman honours. Licurias was runner-up in the Copeland Trophy in 2004.

He barely missed a game across six-and-a-half seasons, fronting up to any challenge that was thrown at him. As his career wore on, though, that trademark resilience he had become renown for loosened a little, as his well-travelled body began to fail him for the first time. A calf injury restricted him to only 11 games in 2007, and it brought about an emotional retirement, announced at Copeland Trophy night.

Fittingly, for someone so connected to the club, Licuria has never really left Collingwood. In various roles over the years – as a VFL player assisting the young group, as a midfield and development coach, and more recently, as a board member, the kid who grew up barracking for the black and white is still giving back to the club.

He wouldn’t have it any other way.