By Glenn McFarlane, of the Herald Sun

Collingwood endured a difficult 1987 season, but the exciting core of young players coach Leigh Matthews had placed his faith in looked set to provide big dividends.

As the club's ruck coach Peter Keenan said in a newspaper column that year: "Some of the old-time Collingwood faithful are saying this is the best crop of Magpie kids they've seen ... Maybe Collingwood has learnt the lesson. A cheque book doesn't make a great club."

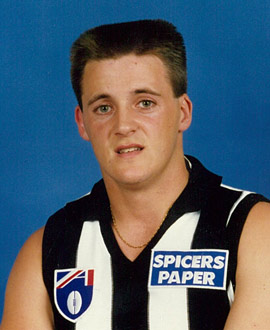

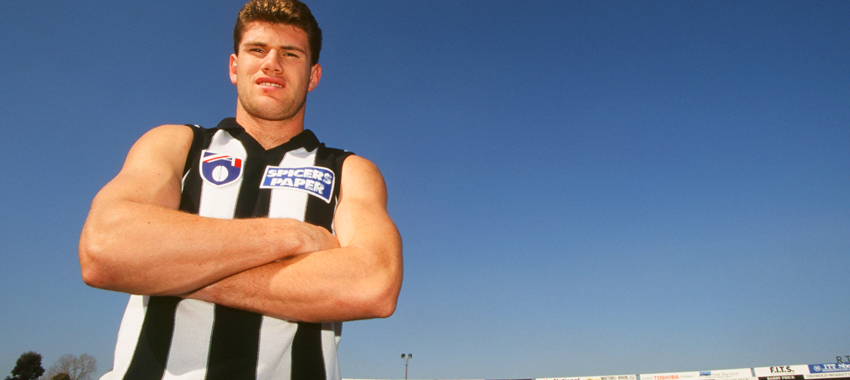

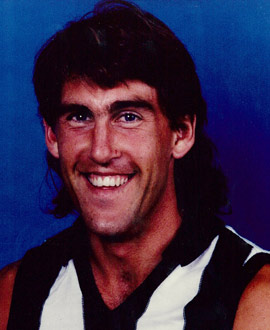

One of those exciting prospects was a powerfully-built teenager from Hamilton, who was among the first intake of Coventry House residents along with fellow youngsters Gavin Crosisca, Mick McGuane, Greg Faull and Brett Gloury. He stood at 188cm, appeared to have the necessary talent, both forward and back, and seemed destined to have a long and fruitful career ahead of him.

His name was Mark Orval, and in only his sixth league match, he gave a significant hint of what was meant to come afterwards. He had been brought back from a one-week suspension for striking young Demon Jim Stynes for the Round 22 game against Essendon. Such was the regard he was held in, Matthews chose him in preference to the previous year's Coleman Medal winner Brian Taylor, who was sent back to the reserves.

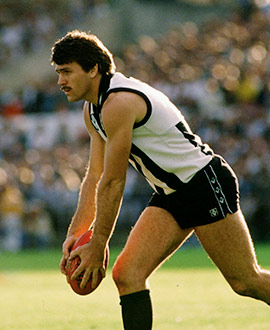

In a classic encounter in the final game of 1987, Orval was one of three players to kick four goals for the Magpies (along with Peter Daicos and Craig Starcevich) out of the team’s tally of 23 goals.

It was a thrilling finish, with the Magpies storming home to win by five points. The 19-year-old had 10 touches, five marks and kicked 4.2 - and he seemed to be ready to take on a key position mantle for years to come.

Matthews couldn't have been more impressed with Orval’s performance, highlighting the spread of forward goals. "To kick 23 goals with several players contributing was pleasing," the coach said. "It's got nothing to do with Taylor out; we would prefer to have our goalkickers spread out as would any club."

But a cruel twist was to follow.

A series of stress fractures in Orval's left foot – the dreaded navicular - cut short his league career. Sadly, he would play only one more senior match - for a total of seven - as he fought a constant battle against the injury.

He had first developed soreness in his foot as far back as the middle of 1986 – his second year at the club - when he was playing under 19s and reserves, but hadn't thought too much about it.

He would say later: "I thought it was ligaments. Not long after that I couldn't bloody walk."

Told to rest, he returned in the 1987 preseason and won a jumper change after an impressive effort in a practice match. He had worn No.54 in the reserves, but after a scuffle in the practice, when he stood up for his teammates, he was thrown the No.10 jumper.

Orval would recall: "There was a bit of a blue going on so I was throwing my weight around. When I came off, the property steward thought I was all right, handed me No. 10 and told me I could keep it!"

By Round 16, 1987, he was chosen for his debut game against Hawthorn. The Hawks won by 125 points, but Orval still managed nine disposals and kicked two behinds. He kept his place in the senior side for the next five weeks, before the Stynes ban gave him an enforced week off.

His breakthrough game against Essendon came in that last round, but it didn’t come without some pain. In an interview four years after the match, he explained how his foot was causing discomfort: "In the last game of the year, it gave way; only then was it diagnosed as a stress fracture."

That began a series of operations that seemed to go on for years.

First, he had a pin inserted in his foot, and the surgeries gradually became more intrusive. None of them seemed to make a difference. Each time he tried to come back, he had soreness.

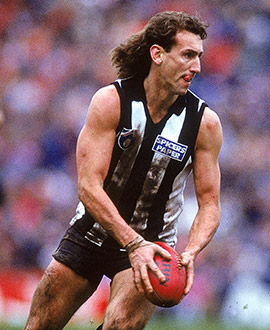

In late 1988, he managed to get through two reserves games and the club thought so much of him that he was recalled for the final match of the VFL season - a year to the round from his four-goal haul.

It came against Geelong, but his afternoon was short-lived. He had only two disposals - and kicked a goal - before his foot "opened up again", leading to more and more surgeries.

Only one reserves game followed in 1989, yet the club stuck with him, mindful that he could still prove a key player in the future if it could somehow fix his foot issues.

In a story in the Sun in 1989, he insisted he would fight on. "If I gave it away now, I'd be forgotten in a month, whereas Collingwood will go on forever," Orval said.

"Daics told me: 'Don't give in, keep going' and I intend to. Daics has been through it too (a run of injuries), though not quite as serious as I've had."

Orval travelled to various medical experts around the country seeking advice, with countless surgeries to try and strengthen the navicular joint.

"The specialist says the fracture has healed and right now, it feels like I could run a marathon," he said in 1989. "But it only gets sore again if I train on it three or four times a week."

The frustration was two-fold. He was one of the more popular members of the playing group. He was also part of Matthews' plan going forward - and there is little doubt he would have at least been right in the mix to be a part of Collingwood's drought-breaking first premiership in 32 years in 1990.

Instead, he was on the sidelines still.

By the middle of 1991, one newspaper said his left foot looked as if it had been put "repeatedly through a butcher's mincer". He had had as many surgeries as senior games played.

He conceded at the time: "I don't think many blokes have gone through this much ... (but) the club's been terrific and my teammates have been great."

"They're always right behind me, but it gets to the stage where, mentally, it drains the shit out of you. I've trained so much it feels like I've played 1000 games.

"It keeps getting to the stage where I'm ready to pull the boots on and it happens again."

The one question he wanted answered, he couldn’t get. "I just want to know how good I can be". He added: "Maybe if I had played the full year in 1988, I could have turned out to be no good and the club could have flicked me. I just don't know ... but I want to."

Nobody who saw him play that day against Essendon thought he was “no good. His foot, more than his talent, had been the problem.

He was delisted at the end of 1991, when he was not yet 24. But, fortunately, he wasn't lost to the club. Orval would go on to serve on the past players' executive for a time, and remains a popular former Magpie.

He would even offer Essendon champion James Hird some advice when he went through his own navicular issues, which almost derailed his career.

Better still, the fame that eluded him at Collingwood came in a very different guise. He would emerge with internet fame in recent years with the Angry Dad posts his sons Dylan and Mitchell turned into an online sensation. The pranks turned out to be exceptionally popular, and one of their Facebooks pages had more than 200,000 likes.

Dylan also spent time at Collingwood as part of the VFL list in 2014, and would later be rookie-listed by Adelaide.

If anyone deserved that change in fortune, it was Mark Orval. If fate had been kinder to him, he wouldn’t be a one-hit wonder; he could have been one of the club’s genuine stars. But, given what happened, at least we saw what he was capable of in that final round game against Essendon back in 1987.