Over the years, the Magpies have made something of an art form of throwing promising youngsters in at the deep end – debuting them in finals or massive home-and-away matches such as Anzac Day. But very few Collingwood rookies have had to endure an introduction as torrid as Len Thompson.

It wasn't just that his debut came in a preliminary final. It wasn't just that it came after first having to endure a nervous wait to see if he could beat a striking charge from his reserves semi-final. And it wasn't just that he was up against Essendon's Don McKenzie, one of the game's hardest and most experienced ruckmen.

It was all of those things – and more. For the game in question, the 1965 preliminary final, was one of the most ill-tempered games in VFL/AFL history. Essendon half-forward John Somerville was knocked out 40 metres behind play in the opening minutes of the game, and much of the rest of the game was brutal.

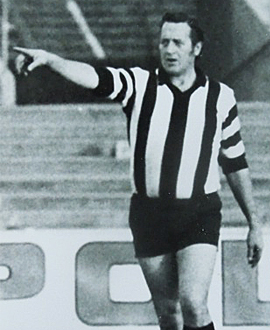

But Thompson, who had only just turned 18, survived. In fact, he did more than that: he had 26 hit-outs that day, to go with 11 kicks and five handballs. He also copped a fearful hammering from McKenzie. But where so many of his teammates wilted in the intensity that day, Thommo stood tall.

Having not just survived but flourished in the face of that test, it was probably no surprise that Len Thompson would go on to enjoy a magnificent career. By its end he had won a then-record five Copeland Trophies, a Brownlow Medal and numerous other accolades. He had also redefined what was possible to expect from a ruckman, combining height, marking ability and exquisite tap skills with almost freakish agility and athleticism. He set the tone for Peter Moore and others to follow with the trend towards mobile big men.

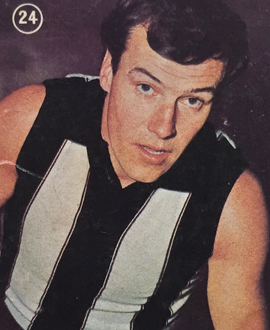

And it all began on that crazy preliminary final day in 1965. Thommo had been a reluctant recruit to Collingwood, having been a passionate Richmond fan as a kid. But the Pies had been watching him as a ruckman with North Reservoir's under-age sides and weren't about to let him go anywhere else. He started with the under-19s in 1964, and had spent most of 1965 with the seconds before fate intervened and provided him with his first senior opportunity after the four other ruckman on the list all succumbed to injury (the fourth, ironically, in a marking contest with Thommo at training). And so it was that Big Len made his debut in that fateful preliminary final as the side's No.l ruckman.

The next year, Thommo set about proving to all and sundry that what he'd shown on debut was just a teaser. Not since Des Fothergill had such a young player made such an impact on league football. In 1966, his first full season, he led many media awards for much of the year and eventually finished third in the Copeland Trophy. The next year he won the Copeland, as well as the first of many Victorian jumpers, then made it back-to-back Copelands in 1968 and finished second in 1969.

He quickly became the dominant big man in the VFL. His 199cm frame made him the second tallest player in Collingwood's history to that point (behind Graeme Fellowes) but his game was based on much more than height. He was a magnificent mark, whose judgement and reading of the flow of the game was superb. Like Terry Waters his marks in the last line of defence became a trademark.

He was also one of the finest exponents of ruck play the game has ever seen. His tap work was deft and delicate, almost artistic. He quickly formed a magical partnership with first rover Wayne Richardson, who had debuted just a few games after Thommo. “I can’t explain the understanding we had,” Thompson said in a 1991 interview. “I just knew instinctively where to hit it, and he knew where to run. We hardly ever said a word to each other in terms of calling or anything – it just happened. He knew the best place for me to palm the ball, and his eyes told me so.”

But the thing that stood out about Thommo – the thing that reallyset him apart – was his agility. He moved like a rover at times, and his ground play and ball skills were astonishing for one so tall. He could pick the ball up on the run, sidestep, handball beautifully, short pass or kick long. He could do it all. If you doubt this, search YouTube for footage of Collingwood's 1973 preliminary final over Richmond and look for his first goal, about halfway into the opening term. Max Richardson taps the ball out to him and Thommo speeds away from Tiger wingman Francis Bourke and sinks a long goal from centre half-forward. Then remind yourself that this bloke is nearly 200cm tall – and he's playing like a midfielder.

Despite his placid nature – Thommo really was the classic gentle giant on the field – he had an unhappy knack of courting controversy. The most famous instance of that, of course, came during the 1970 pre-season, when he and Des Tuddenham went on 'strike' for a few weeks in a fight for better pay and conditions, sparked by the club's decision to spend big on WA recruit Peter Eakins. The strike was front page news for weeks. It was eventually resolved, but the pair's actions left a bitter aftertaste.

To make matters worse, that 1970 incident set a trend: seemingly every second year or so Thommo would threaten to leave, or announce he was leaving, if his latest wage demands weren't met. The result was that, despite winning three more Copelands in the 1970s and the Brownlow Medal in 1972, Big Len often felt that he was resented by some fans, and certainly by some officials.

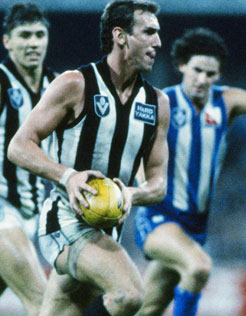

That feeling was exacerbated when Collingwood pushed him out at the end of the 1978 season. He had finally been named skipper that year but Tommy Hafey decided to off-load him as part of a major clearout at season's end. Thommo desperately wanted to stay and become the club’s first 15-year player since Lou Richards, but instead he had to end his career at South Melbourne, then Fitzroy, eventually finishing with a grand total of 305 games. He returned to Victoria Park briefly in the mid-1980s as part of the ill-fated New Magpies regime.

Len Thompson's stellar career stamps him as one of the greatest Collingwood footballers of all time. Yet he still felt there was resentment towards him even after retirement, and he admitted to feeling uncomfortable or 'on edge' at club functions. But all that changed after Eddie McGuire took over as president. His whole-hearted attempts to bring disenchanted former players back into the fold had perhaps their greatest success with Thommo, who finally found his way back to widespread acclamation in the early 2000s. When he died of a heart attack in 2007, aged just 60, the club mourned.

But Thommo's journey with Collingwood wasn't quite finished yet. In 2014, his Brownlow Medal and three of his Copelands were donated to the club by an anonymous benefactor. They now form part of the club's archives, where they will forever remain as testament to an extraordinary and yet perhaps still undervalued career.

- Michael Roberts