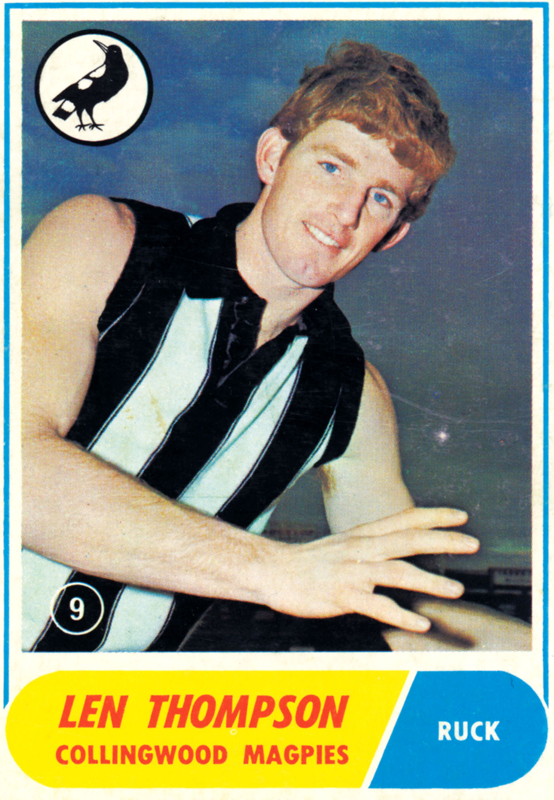

The Collingwood teams of the late 1960s and early 1970s were some of the most exhilarating the football club has ever put on the park, featuring stellar names such as Len Thompson, Peter McKenna, Des Tuddenham, Wayne and Max Richardson, and Barry Price.

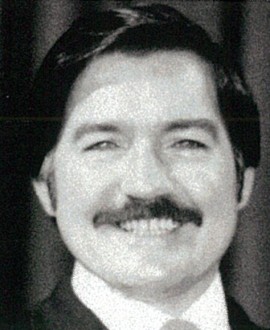

But the best of them all, at least in terms of pure talent, might just have been a quirky, driven kid from Tasmania called John Greening, who wowed his clubmates from the moment he walked into Victoria Park and who looked set to dominate the VFL until an act of thuggery cut short what could have been one of the all-time great careers.

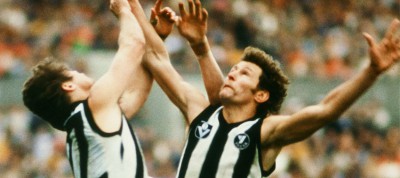

Those talents, both individually and collectively, were never better displayed than in the Round 4 game against Carlton in 1969. In one of the most remarkable and spiteful matches in VFL history (there were so many reported players that all of them got off because the umpires missed the deadline by which reports had to be submitted), the Magpies smashed the reigning premiers at Princes Park by nearly 11 goals. The Pies played breathtaking football that day, especially during a stunning 12-goal blitzkrieg of a third quarter.

The star of that remarkable show was Greening, then just 18 years old and playing only his 19thgame of VFL football. He kicked 7.3 as a ruck-rover that day, and the TV highlights of the game that survive show him running fast with that long, loping stride of his, dodging, baulking, linking-up with teammates and kicking goals from everywhere. He'd kicked five goals against Melbourne the week before, and suddenly everyone knew his name: John Greening had arrived.

He had landed at Victoria Park just over two years year earlier as a prodigiously talented junior sportsman who had been likened in his home state to St Kilda legend Darrel Baldock (the boys' sportsmaster said Greening was actually the more talented of the two). He was born and grew up in Burnie, but was a mad keen long-distance Collingwood fan as a kid, following them on his old Astor radio and dreaming of nothing more than being a star in the VFL.

“Football was everything to me,” he said in 1991. “I was motivated by the dream of playing in the VFL. From the time I was 12 or 13 all I wanted to do was get away from Burnie and play in the VFL. I’d even get a high just listening to Collingwood games on the radio.”

Greening came to Collingwood as a 16-year-old who'd never played senior football. He spent 1967 with the thirds and seconds, and the seemingly straightforward trajectory continued when he made his senior debut in the fifth round of 1968. He would not miss a game again until fate intervened in 1972. Those champions who played alongside him were in awe from his earliest showings at the club.

“John Greening was the most talented and exciting footballer I ever saw,” said Peter McKenna. “Honestly, he had more talent in his little finger than just about anyone else at the club at that time.” Terry Waters said he could tell Greening was special from the first time he saw him. “He could have been one of the best ever,” he said. Bob Rose, too, couldn’t disguise his excitement. “I thought he was the best young player I had seen,” Rose said years later. “Quite simply, he could have been anything.”

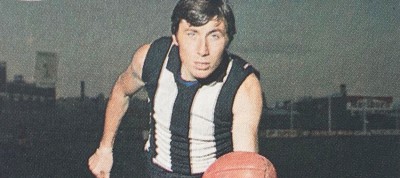

After those breakout games early in 1969, it was clear that Collingwood had found a true star of the game. He was ideally built, at 185cm and 82.5kg, supremely gifted and full of self-confidence. He was lean, lithe and fast, highly skilled on both sides of his body and one of the cleanest ball-handlers in the game. He could run all day – fast – fly for the biggest grabs, roost the ball long distances with raking kicks or deliver spearing passes to McKenna on a plate. And he loved a goal.

He spent most of his time playing either in the centre or as a ruck-rover, with occasional stints on a wing or at half-forward. Wherever he played he quickly established himself as one of the most exciting players not just at Collingwood but also in the competition. Watching the young John Greening play football was a joy: here was a naturally talented athlete who played with such freedom and uninhibited audacity that the next freakish moment never seemed far away. And best of all, you could tell that he loved it too.

“VFL football was just so exciting for me,” he said. “It was everything I wanted it to be – and more. I thrived on the harder training, and with the extra fitness and strength it gave me I found I reached new heights in my football. I was just fanatical about it.”

Greening had started young and was a fitness fanatic, so even as his career entered its fifth season in 1972, he was only 21 and looked likely to have a decade in front of him. Later on, he would say that he could have played until he was 40 – and that the VFL games record wouldn't have been beyond him. He wasn't joking.

But he never got that chance. As is now well documented, Greening was all but knocked out of football. He was in the form of his life in 1972, and by mid-season was leading many media awards (he would go on to finish third in the Copeland and seventh in the Brownlow Medal despite playing only 13 games). Against St Kilda in Round 14 he took the first mark of the game, kicked it to the goalsquare and was then felled behind play while everyone else was watching the flight of the ball.

Greening was carried off on a stretcher, blood trickling from his nose and mouth. His injuries were probably the most serious ever suffered by a Collingwood footballer during a game. Doctors feared for his life: he was comatose for 24 hours, and it was days before he regained full consciousness. He suffered cerebral concussion and was initially expected to be permanently disabled. A young Eddie McGuire was one of many supporters who spent days praying for him.

No player was reported, but Collingwood laid an official complaint. The League inquiry that followed led to a striking charge being brought against Jim O’Dea, and the tribunal suspended him for 10 weeks. A writ for alleged assault was also filed with the Supreme Court but later withdrawn.

It was the biggest sensation in football for years – one of the game's best young players cut down in his prime. There was outrage and anger and disbelief. Some fans were so sickened by what happened that they never went to a game again. Some still want to see an apology or signs of remorse.

But Greening was a fighter. He proved the doctors and doubters wrong, and fifteen months later pulled on the boots again in a social game. He returned to pre-season training at Collingwood early in 1974. And then, after a few reserve outings, he came back to senior football in one of the most emotional moments Collingwood has ever seen. He led the team out that day, booted a goal with his first kick, took a speccie and was one of the best players on the ground as the Magpies thrashed the reigning premiers. No Collingwood fan who saw that game will ever forget it.

But counter-intuitively, that comeback was also the beginning of the end. Greening had been sodetermined to prove to everyone that he wasn't brain-damaged, that he was as good as ever, that having achieved that there was a major letdown afterwards. The lack of preparation told and he tore a hamstring in his second game back. Then motivation became a major issue. He lost confidence, touch and even interest. His personal life suffered, too, and he battled with depression. In the end he managed only a handful more senior games before ending his career in 1976.

John Greening eventually found peace with his life. He doesn't like to dwell too much on the incident that cost him so much, but in 1991 reflected that he would sometimes wonder – as anyone would – why it had to happen to him. He has been back to the club a number of times in recent years, most memorably for his induction to the Collingwood Hall of Fame in 2011. The standing ovation he received that night was as telling as it was emotional: the fans weren't lamenting what might have been, they were celebrating what was. And in John Greening's case, that's a career – and a talent – which is well worth celebrating.

- Michael Roberts