Arguably the greatest figure in the club's history, Jock McHale played for 17 seasons, coached for 38 — yes, 38 — and provided the leadership, spirit and inspiration that kept Collingwood at or near the top of the football tree for the first 50 years of the 20th century. Even today, his name is synonymous with Collingwood.

James Francis McHale (he did not become known as Jock until the newspaper cartoonist Sam Wells began using the nickname well into his career) was actually a native of New South Wales, having been born at Botany Bay in 1882. He moved to Melbourne at the age of five with his parents and first went to school at St Brigid’s in North Fitzroy. Then it was on to St Paul’s at Coburg and finally Christian Brothers’ College in East Melbourne, where he first played competitive football.

After leaving school, he joined up with Coburg juniors, and played with them from 1899 to 1902. He tried out with Collingwood in 1902 but was rejected. Former club committeeman Jack Duncan saw Jock kicking a ball around a local timber yard and invited him back to Victoria Park for another try. This time, luck was on Jock’s side. Not long after, he was chosen as a member of a combined juniors team to play the reigning premiers, who just happened to be Collingwood. McHale played a blinder in the centre against the great Fred Leach and was immediately promised a spot on the Magpies' senior list for 1903.

Indeed he was chosen for the opening game of the year against Carlton, breaking into a Premiership team to do so. He played 14 of a possible 19 games that season, embarking on a career virtually unparalleled for consistency of service. He did not miss a single match from the 13th round of 1906 to the third round of 1917 — a phenomenal 191 games in a row. Excluding his first and last full seasons (1903 and 1917), he missed only two games in 13 years and, in his 15 years of full availability, played 259 of a possible 275 games — a mind-boggling feat of endurance, fitness and dedication.

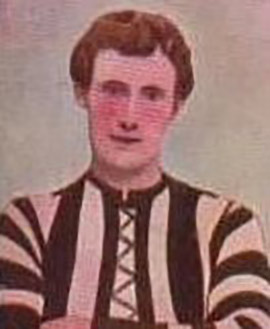

Initially he played as a half-back, but after several seasons in the position he was moved into the centre, and it was here that he really came into his own.

Standing at about 180cm (5ft 11in) and weighing some 78kg (12st 4lb), McHale had a splendid build for playing in the pivot. He was a tireless worker in the middle and would run all day, playing hard from start to finish. He hated losing, and would work himself into the ground in his efforts to secure victory. Although not the most brilliant player of his day, he was a good centreman and a player of extraordinary cunning and nouse. His reading of the game and his assessment of opposition players were legendary, even early in his career. He was quite speedy, regularly working on his running during the summer months, and strong. He was an excellent ball-handler, a capable mark and a reasonable kick, though he was sometimes criticised for punting the ball high into the forward line rather than using low, direct passes. Overall, his skills, combined with his forceful play, helped make him one of the most competitive centremen in the League.

His playing abilities were frequently recognised by VFL selectors and football critics. The players, too, recognised his outstanding leadership qualities, electing him captain in 1912, 1913 and 1917 (though Percy Wilson took over later in the last of those seasons). At the end of 1917, the first season since 1903 in which he had missed more than two games, he decided he would only play in 1918 if the team was short of players. He was needed only once, against Essendon. Jock was pressed into action for a final time in the first game of 1920, as a last-minute replacement for the injured Alex Mutch. But his playing career effectively ended in the grand final of 1917.

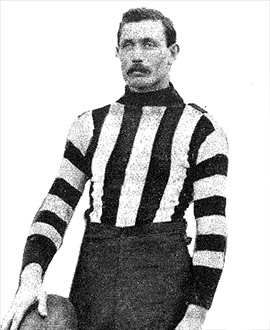

Even in his heyday as a player, it was clear that Jock had other challenges in store for his nimble football brain. As a result he became involved in coaching quite early, although he was not, as many people think, the Woods’ first coach. Bill Strickland, Dick Condon, Ted Rowell and George Angus had all had a go before Jock got a chance to take hold of the reins in 1912. In 1912 and 1913 he acted as captain coach, from 1914-17 as playing coach and from 1918-49 as non-playing coach. By the time he'd hung up the clipboard he had been in charge for a record 714 games, a mark that was not passed until Mick Malthouse in 2015.

Under his leadership, Collingwood teams were Premiers eight times and runners-up a further nine. That is almost a Grand Final appearance every second year. Staggering.

McHale's coaching career is covered in more detail here. His great strength as a coach lay in his ability to prepare and inspire players, and instil discipline into the team’s game. He employed a strict game plan and training methods that drilled the plan home. He was a firm believer in players keeping closely to their positions during a game, and reinforced this through frequent use of match practice at training. The result of this regimented training was a superbly disciplined team that always adhered to a predetermined game plan, especially up forward.

The inspiration came from the man himself. He was single-minded about football, and success for Collingwood in particular. He loved the club, and devoted much of his life to it. McHale did not believe in stars (even to the point of insisting on receiving the same pay as his players), and had his charges thinking and playing as a unit. He hated losing. He hated timidity on the field, as he regarded that as a betrayal of the guernsey. His passion for Collingwood really shone through in his half-time addresses — soul-stirring, inspirational orations that invoked the club spirit and could lift players to extraordinary heights.

McHale was a quiet man by nature but with a firm resolve that won him respect and admiration everywhere. He was honest, frank, a straight-shooter. The players loved him, though few really got to know him well. Many over the years referred to him only as “Mr McHale” or “Sir”.

He was one of many Collingwood players who worked at Carlton and United Breweries. He had done so since a lad and was a strong supporter of his employer’s products. Despite his fanaticism for fitness, McHale believed it was “the best thing out” for a player to have a glass of ale when fatigued. “There is no need for a man to wash himself in it,” he once said, “but a taste now and again is the best thing going.” He even appeared in anti-prohibition ads that ran prominently in newspapers in 1930.

McHale enjoyed so much success over such a long period that his tenure in the position of coach was rarely, if ever, questioned. But as the team endured a largely bleak 1940s, it increasingly became clear that McHale, though still revered by all at Collingwood, was past his prime. Even so, he only made the call to retire just prior to the 1950 season. In his last address, at a practice match, McHale told his charges. “I would do anything for the club — I always would since I joined it in 1903. I am a sad man today, but I will be delighted if this grand side goes on to big things” he said.

That “grand side” did go on to big things, taking out the Premiership three years later. But barely had the celebrations ended when the mourning began. McHale died only days after the 1953 Premiership victory, adding an unexpectedly poignant note to the triumph. The heart that many thought pumped only black and white blood finally faltered. Some people felt the excitement of the Premiership win may have contributed to his death (and that soon afterwards of John Wren), for his initial heart attack occurred on the day after the match.

Fortunately, his son, “young” Jock (really, John), was there to carry on the family name. He played more than 30 games, was a committeeman for many years and, in a nice touch, was given the honour of unfurling the club’s historic 1990 Premiership flag.

Still later, Jock McHale himself would be recognised by the AFL when the medal awarded to each year's Premiership coach was named in his honour. That was a fitting tribute to a man whose extraordinary coaching career almost defies belief. But so does his playing career. And his overall contribution to Collingwood - his record of service and loyalty to the club - will likely never be matched, let alone bettered.

- Michael Roberts