It isn't often that a footballer is likened to a 'fire-breathing dragon'. But that's the tag applied to Jack Hamilton back in 1951 – and few of the forwards he ever lined up against would have argued with its appropriateness.

Hamilton, of course, would later go on to run the VFL and become the game's first full-time commissioner, where some of those dragon-esque skills would come in particularly handy. But his profile as football's most powerful administrator has tended to overshadow his achievements as a footballer three decades earlier.

And those achievements were significant. He played more than 150 games, represented Victoria and was, for a time, regarded as the best full-back in the game.

But Jack Hamilton should never have been a Collingwood footballer at all. He was born and raised in Ivanhoe, attended Northcote High School, then played with Ivanhoe in the amateurs before a Carlton recruiting officer approached him in 1945, when he was 16. Jack was a Blues fan and would love to have played with them, but admitted to the official that he lived 20 yards inside Collingwood’s territory.

The Blues official, to his credit, contacted Collingwood, who invited Hamilton down for a trial. He filled out some paperwork, played a couple of reserves games, then returned to Ivanhoe for two more seasons. The Magpies kept their eyes on him, however, and brought him back to Victoria Park for the 1948 season, where he started his career with four senior games.

Years later, when Hamilton was working at the VFL, he discovered that the street in which he grew up actually had been 20 yards outsideCollingwood’s zone in an unallocated area that meant he could have played anywhere. And years later again, he discovered that his paperwork had never actually been completed!

By this time, of course, Jack Hamilton was a dyed-in-the-wool magpie and nobody – other than maybe Carlton – had cause to regret the administrative oversights that had helped deliver the old-fashioned, rugged defender to Victoria Park.

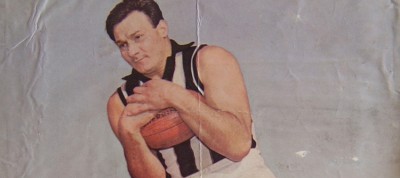

He arrived there as a strongly built half-bank flanker, and that's where he played his first 40-odd games of senior football. But in 1951 he was shifted to full-back, and his impact there was phenomenal, winning interstate selection and being named full-back in the Sporting Globe's Team of the Year. And that's where the dragon comparisons emerged.

"Hamilton has a vigor and robustness that ruins contemplation and upsets orderly attack," wrote the Globe's Hec de Lacy. "He has improved out of recognition as a footballer. He adds to this gift for the game an outlook of aggressive defence that defies the best attacks to break through. Hamilton has brought to his play a dash and determination and anticipation. He moves from the goal square like a snake, striking and, most times, intercepts an attack whereas a man of less purpose would not quite catch up with the chain of odd-man passes. He is the fire-eating dragon that stands guard over the Magpies' goal. He spares neither prince nor peasant – neither a Coleman nor a first game trial-horse. If he's beaten he goes down snorting and wrestling like a war horse with his feet in a bog."

Those words summed up Hamilton's style of play perfectly. He wasn't a polished player but he read the game well, could take a decent mark, was an effective spoiler and had good pace, especially when charging out from defence. He was also immensely strong, being one of the first footballers to take up weightlifting to build on what was already a naturally superb physique.

There was also a craziness and unpredictability to his play that must have made him a nightmare to play against – and could also make life difficult for his own teammates. “He was as rugged as anything," said fellow defender Peter Lucas. "He’d come charging through, legs and arms going everywhere. The other defenders always used to say ‘stand clear – here comes Jack’ every time he’d come charging out from goal. He would just hit wherever he saw the ball and a player, and it didn’t always matter whether it was a Collingwood player or not.”

With a good record against pre-eminent full-forwards like John Coleman, Hamilton seemed to have the key defensive post sewn up. But knee problems forced him out for much of 1952 and a broken wrist kept him out of the 1953 finals. The more stylish Jack Finck took his place while he was out and kept it when he returned, so Hamilton squeezed in up forward again. But when Finck himself retired in 1954, Jack reclaimed his spot in the last line of defence, and it was there that he turned in a memorable lone-hand performance in the losing grand final of 1955.

He retired after the 1957 season but, while he took on a job with Frankston as captain-coach, his burgeoning administrative career at VFL headquarters was taking up more and more of his time. He'd started out as a clerk there just after his footy career began, and he eventually rose to take over as general manager after Eric McCutcheon's retirement in 1977.

Hamilton won enormous respect during his time at the top as he guided the game through one of its most turbulent periods, featuring bitter legal battles, South Melbourne’s move to Sydney and other early steps towards a national competition. He was awarded an Order of Australia in 1984, the same year in which he was appointed the VFL’s first chief commissioner under a radical new League structure.

But Hamilton wasn't just respected: he was also greatly loved. No other League boss before or since has commanded that level of affection. The reasons lay in Jack's warmth, his love for the game and his wicked and ever-present sense of humour. The last of those was legendary. When he suddenly retired from his VFL role in 1986, he was asked if might take on an official role at the then-struggling Collingwood: “Look," he replied. "I’ve just got off Devil’s Island — I’m not going to live on Alcatraz.”

Instead, he supported the Magpies (or 'Carringbush', as he preferred to call them) from a distance. Four years later, as they were heading towards that famous drought-breaking 1990 Premiership, Jack Hamilton was killed in a car crash near Whittlesea, sparking an extraordinary outpouring of affection and warmth from the football family.

His widow, Joan, later said it had been his dream while VFL Commissioner to present a Collingwood captain with a Premiership cup. But the AFL – as it was by then – did the next best thing, and Tony Shaw took the cup that day from Jack's son, John. That added the final touch of magic to an already magical day.

- Michael Roberts