In a quirk of fate that will delight most Magpie fans, Carlton has been an unwittingly generous supplier of talent to the black and white cause.

In 1893 the Blues provided the Pies with Billy Strickland, the man who just a few years later led the club to its first Premiership. In 1913 they dumped Harry Curtis, who was picked up by Collingwood and played for 10 years, captained the club and then served as president for a record term. In the 1920s Carlton discarded Harold Rumney, who went on to win a Copeland and play in five Premiership teams as part of The Machine.

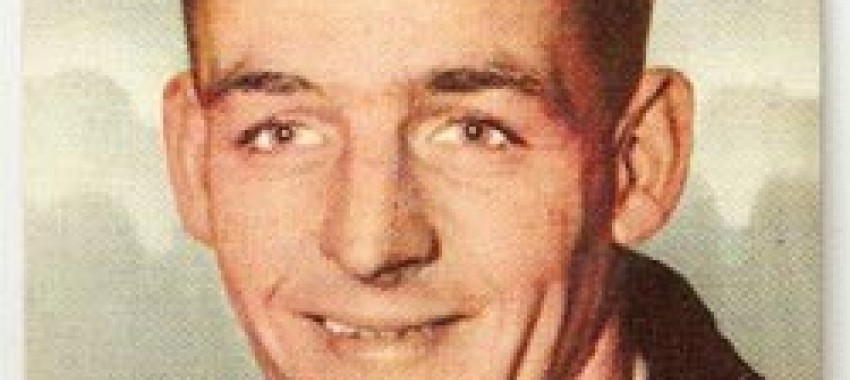

Then, in the 1950s, Carlton virtually put Harry Sullivan in a black and white jumper — and in the process transformed a fringe centre half-forward into a Victorian full-back.

Harry Sullivan had first come to the attention of some perceptive Collingwood scouts a few years earlier, when Gordon Carlyon saw the Carlton youngster take the Magpie thirds apart. Sullivan played in his customary centre half-forward post that day and, according to Carlyon, “marked everything in sight”. It was a performance which, as time passed, would become more significant than it first appeared.

Sullivan’s early days at Carlton were encouraging. He started with the thirds as a 17-year old in 1949, and took off the award for best and fairest. He spent the next year in the seconds, was blooded in the firsts and performed well enough to play 14 senior games in 1951.

But then his progress stalled, and he managed only another 15 games in the next three years. He was still young, but Carlton lost both patience and faith. Sullivan began to look around and ended up speaking to Carlyon, who had not forgotten the young man’s performance from years before. Carlyon convinced Sullivan that Victoria Park was the place to be, so Harry turned up to Carlton’s last practice game of 1955 and told the chairman of selectors he wanted to leave. His only response was: “All right, off you go then.”

Sullivan made it to Collingwood’s ground just in time to be squeezed into the late “probables v possibles” game, and performed so well that he was named at centre half-forward in the seniors for the opening round of 1955 against the reigning Premiers, Footscray. Unfortunately Harry ran into a fired-up Ted Whitten, and old “EJ” gave him “a bit of a bath”.

Sullivan was not surprised to be dropped, but he was surprised to find that seconds’ coach Jack Pimm had named him at full-back. It turned out to be the move that saved Harry’s flagging career.

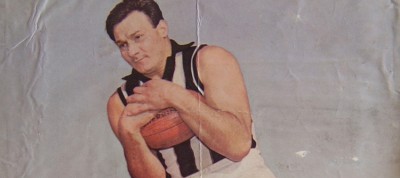

In his first game as a full-back, Sullivan was best on the ground. Over the next few weeks he gradually regained form and confidence in the seconds, learning more about his newly-adopted role as a key defender. He did get a few more chances at senior level in 1955, but these were again in a variety of positions. It was not until midway through 1956, after injuries to key players including Jack Hamilton, that Sullivan got his first real chance as a senior full-back. A few games after his return he lined up in that position against Carlton, and promptly rubbed salt into his old team’s wounds by winning Collingwood’s vote as best player. He repeated the dose the following week against Geelong, and his future was sealed.

The secret to his renewed success was his suitability to the full-back post. He showed an immediate liking for the straight-ahead, counter-play of full-back, where his ability to read the game proved even more valuable than it had as a forward.

At 185 cm (6ft 1in) and 82.5kg (13 stone), Sullivan’s major strengths had always been his natural spring and his strong marking. At the age of 16 he had won the inter-technical schools’ high jump championship with a jump of 5ft 8in (173cm), and at full-back this spring was still a potent weapon. He had terrific hands, and his marking was sure and usually one-grab. As he became more defensively-minded, he often chose to fist the ball away in preference to going for the mark — making him an even better backman.

He had a good temperament for defence, being regarded as sensible, reliable and level-headed off the field as well as on. He was also a great communicator. “He was fantastic at calling to teammates and telling them how they were placed,” fellow backman Ron Kingston once said. “He was a great bloke to have behind you, because he would talk all the time and you knew you could trust his calls.”

As his football career developed, so too did his business interests. In business, as in football, his level-headed approach produced results. After leaving school (where he had captained the football, cricket and athletic teams) Sullivan worked with his father at a hairdressing supplies company. His determination for success was such that he soon left and, aged only 19, bought a rival business. So successful was Sullivan’s Hairdressing Supplies that it was eventually able to buy out the company where Harry had first worked!

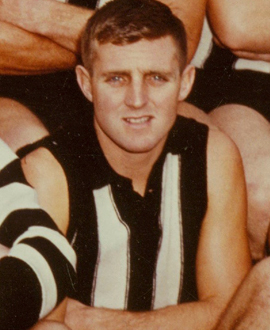

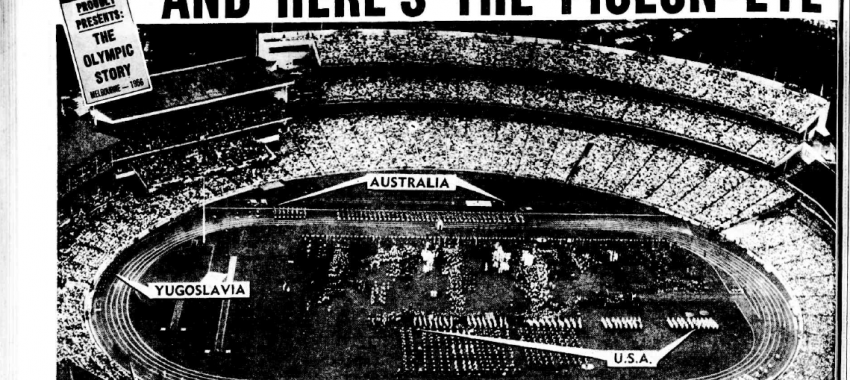

He settled in well at Collingwood and this was reflected in his play. After a consistent 1957, Sullivan’s career peaked in 1958. He finished third in the Copeland Trophy, won selection in the Victorian carnival team, was named in the Sporting Globe’s team of the year and polled the most Brownlow votes (14) of any Collingwood player or any full-back. Oh, and there was the little matter of a Premiership as well.

His 1959 season was solid, and highlighted by a mark taken over Ron Barassi which Melbourne coach Norm Smith described as the best he had seen since the Second World War. Collingwood recognised it by issuing a commemorative cup, saucer and plate set and an ashtray, each bearing an artist’s depiction of the mark.

In 1960 Sullivan’s form began to slide. He fronted up for the practice matches of 1961, but when he found himself in one of the “probables v possibles” games he knew it was time to consider life after football, even though he was only 28. He devoted himself virtually fulltime to business, though he later spent several years as a panellist on the ABC’s Saturday night footy show. There he became well regarded for his calmness, astute reading of the game and ability to communicate – skills that had served him even better on the field than they did in a TV studio. - Michael Roberts