In just his seventh game of VFL football, Harry Saunders had the chance to live out every kid's dream.

A pulsating, hotly contested match on the last day of June between Collingwood and Fitzroy had come to the final minute with the 'Roys leading by four points. Then Alec Mutch sent the ball forward one last time, and young forward pocket Harry Saunders flew into the air and took a great mark. He was more than 40m out but went back and coolly slotted his kick through just as the bell sounded, grabbing a dramatic late win.

The Victoria Park crowd went wild, and Saunders was the hero of the hour. This was the fourth time in his six games that year that he'd notched at least a goal, and he seemed to have a promising career in front of him as a forward. Just two weeks earlier, the Sporting Judge had noted that Saunders "had repeatedly come under notice with his high marks and long kicks". "If we mistake not, this lad will prove a distinct asset to the firing line in the not very distant future." A fortnight later they were proven correct.

So how did Collingwood respond? They moved Saunders to half-back the very next week, of course. By the end of the year he was solid at full-back in a Premiership side, and he would remain the ever-reliable custodian of Collingwood's goal for the next eight years.

It might have seemed counterintuitive at the time, and certainly the move raised more than a few eyebrows. But there was a logic to the Pies' apparent madness. Saunders had been effective as a forward, but not hugely so: five goals in seven games was encouraging, but no more. The things about his game that had attracted most praise were his magnificent kicking and his strong marking – and those were traits very much needed in a key defensive post. Plus the Pies were short at full-back: Pen Reynolds and Maurie Sheehy used to alternate between that position and the ruck, and selectors desperately wanted a permanent full-back. So, despite his last-minute goalkicking heroics against Fitzroy, Saunders was sent to the back line.

It was a move that worked out better than anyone could have hoped. Collingwood found itself a steadying, reliable key defender, and Saunders found himself the niche in VFL football he'd been struggling to identify. In the end he played more than 130 games in just over 10 seasons, served as vice-captain for three seasons and in the early 1920s was widely regarded as one of the best full-backs in the competition.

Saunders was born in Portland (christened Henry but universally referred to as Harry until he picked up the nickname “Sam”, after a famous boxer), and moved to Melbourne as a youngster, attending Christian Brothers’ College in Fitzroy. After school he played with the Collingwood Senior Cadets, where he was spotted by vice-president Syd Sherrin. Harry could manage only a solitary game in his first year, 1916, but he became a regular after moving into defence in 1917.

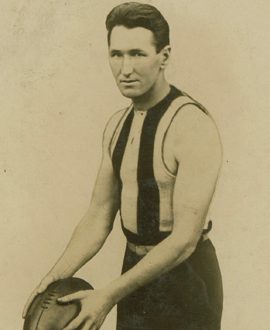

Saunders proved to be exceptional at full-back. He wasn't flashy or adventurous but he was rarely beaten. He was a wonderful mark for his size, renowned for his judgement of when to attack the ball and when to stay at home with his man. He mostly liked to stick close to full-forwards and rarely gave them any room. His kicking was simply superb – he was one of the finest in the league. One former player remarked that Saunders’ kicks were so good “you couldn’t help but mark them”. The Herald rated him “one of the best full-backs ever to have played in Victoria”. By 1920, some judges rated him better in that role than the great Vic Thorp of Richmond. He played for Victoria twice and the VFL three times, and would have done so more often but for Thorp's presence.

The overwhelming sense that Harry Saunders gave to Collingwood's teams was one of solidity. No fuss, few errors, consummate professional. The defensive ship was in good hands.

All of which made him one of the more unlikely candidates to be involved in what turned out to be one of the most controversial incidents in VFL/AFL history, and only the second player to have been convicted by the courts for an on-field assault.

The clash against Carlton in Round 12 of 1922 was typically willing, and Saunders – who had scarcely even been spoken to by umpires in his career – found himself in a confrontation with Blues' centre half-back Alec Duncan (ironically, a good off-field friend). Duncan received three weeks for elbowing Harry, and Harry copped six weeks for retaliating. A police officer on duty at the game said he saw Saunders hit Duncan with two severe blows, which knocked him out cold.

Based on the policeman's evidence, Saunders was hit with a summons charging him with unlawful assault. He pleaded guilty under extreme provocation, saying Duncan had struck him first, then 'shaped up' as if to strike again so Saunders moved to 'get in one first'. Saunders expected to be asked for a contribution to the poor box, but instead was convicted and fined £5 — a result that stunned both him and the club.

Remarkably, given his generally quiet demeanour, Saunders found himself back in court again the following year, this time as a witness in a case brought by the Society for the Protection of Animals against Richmond's Norm McIntosh for kicking a dog to death after it ran onto the field during a game (McIntosh was convicted and fined £2).

Saunders was named vice-captain in 1923, but by 1925 found his game time limited by the new crop of emerging stars. He moved to Footscray as coach in 1926, but was soon back at Victoria Park, helping out around the club. Sadly, he became ill soon afterwards with pancreatitis and died in 1930, aged just 32. The Collingwood Football Club and his workmates at Carlton & United Breweries went into mourning, for Harry had been a much-loved colleague and friend. On the day of his funeral, CUB accorded him the rare tribute of closing down the brewery operations as a mark of respect. And respect was never in short supply when it came to Harry Saunders, one of Collingwood's greatest full-backs.

- Michael Roberts