By: Michael Roberts

Several cricket sides used the Victoria Park ground in the 1880s, most notably the Capulet Cricket Club. Indeed, Capulet proved innovators in terms of ground management, becoming the first local team to erect a portable grandstand. To pay for the structure, they were granted permission by the Council to charge admission to their matches for non-ratepayers in the 1886/87 cricket season.

By that time, the Britannia Football Club had made Victoria Park its home. The Brits played their first matches on the ground in 1882 and continued to use the venue, along with a number of other clubs, until they folded 10 years later. There had also been a Collingwood junior football team in the 1880s. It played on an area known as Sheepsfold, near the Riley St drain and Dight's falls, but the club went out of existence before Britannia came to base itself at Victoria Park.

Britannia had long aspired to winning a place in the state's premier competition, the Victorian Football Association, but several considerable hurdles stood in its path. For a start, the administration of the VFA deemed the club too disorganised and amateurish for its burgeoning competition. The ground also required urgent capital works and extensions before it could be classed as a ground fit for VFA football. Moreover, there was a groundswell of support to form a new team that was truly representative of the suburb in the 1890s – a team that embodied Collingwood in both name and make-up. Britannia, closely aligned with Fitzroy, could never be that team.

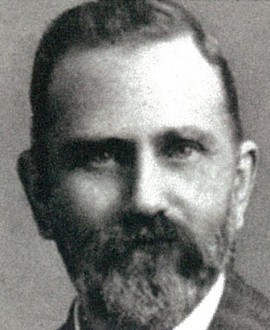

Councillor, parliamentarian and sports devotee W.D. Beazley convinced the Council to spend 600 pounds on levelling the ground and erecting a picket fence around the playing arena of Victoria Park in an effort to impress the VFA. The ground was also extended by 30 yards. Community, business and political leaders kept pushing to form the Collingwood Football Club, and Britannia eventually disintegrated under the pressure. After years of lobbying, the VFA finally relented and admitted the fledgling club for the 1892 season. Collingwood, the inner-suburban, working-class community that symbolised struggle, had won the battle. They could finally boast their own football team and their own ground.

Those doubting whether the community would rally behind the new team were given a rude awakening on Friday, February 12 at the Collingwood Town Hall. In one of the most positive forums in the club's history, a special meeting called to gauge support was met with an overwhelming response. With banners proclaiming ‘Football, Football, Football’ in front of the Town Hall, hundreds of prospective members crammed into the Lecture Hall and many (including a reporter) were forced to follow the meeting's proceedings through an opened window. It was, quite literally, standing room only.

Beazley, born in London but raised and educated in Collingwood, was the chairman of the meeting and the first president of the club. He told the expectant gathering the football club would ‘draw immense crowds and be the cause of much money being spent in the district.’ He referred to the improvements planned for Victoria Park, such as the erection of a grandstand and pavilion, and a substantial fence around the playing ground. He hoped the club's members would ‘be true to their colours, and not be dispirited if they at first lost matches, as they would require one or two seasons to lick them into first class football.’

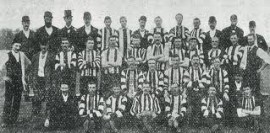

The buzz around the new club grew even louder as the day of the club's first official VFA game drew near. Played against Carlton at Victoria Park on May 7, 1892, it was one of the biggest events in the suburb's history. The weather provided a positive omen, as it was the first Saturday in a month without rain. Collingwood's first match at Victoria Park was billed as ‘a tug of war between the old and the new’, but there was mutual admiration between the two teams (Carlton generously agreed to offer their takings of the gate to the new club).

There were no official gate figures, somewhere in the vicinity of 16,000 flocked to the ground that day – an extraordinary figure for the time. The Mercury swallowed some pride to ponder: "What possible benefit can a football club have on the welfare of the city?" Almost in the same sentence, they pointed to the numbers of fans (local and otherwise) in attendance and "the smiles that radiated from the various countenances of the Johnston St tradesmen ... pleased at seeing such a large influx of persons into the city, as in all probability they left a silver coin here and there."

President Beazley presented the club with a flag to fly over Victoria Park, and one of the club's supporters, Mr Vincent, donated a set of caps for the players to don.

There were only two negatives about Collingwood's birth. Firstly, the timber grandstand/training room that had been promised was not completed in time for the first game. And when it did open a month later, it was nowhere near as palatial as had been planned, the bleak economic climate having severely curtailed the project. So the ground's first permanent grandstand, designed – for free – by Cr William Pitt (the architect of the many Melbourne icons such as the Princess Theatre, St Kilda's Town Hall and Melbourne Stock Exchange), ended up holding just 300 seats – less than half of what had been originally planned.

The other negative that May afternoon in 1892 was the result. Carlton, veterans in the craft, proved too experienced for "the young'uns", winning the first encounter 3 goals to 2 (behinds were not counted in the VFA). But the barrackers of the new club, in a forerunner of things to come, used their lungs to their utmost extent and cheered their new heroes on, regardless of the result.

The on-field effort had been promising, and the off-field results stunning. Victoria Park, and Collingwood, had arrived. There would be no turning back.