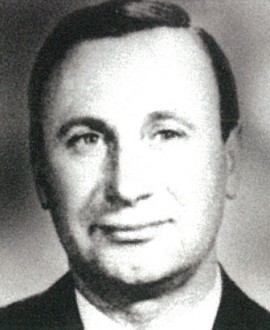

It’s an unfortunate fact that Duncan Wright’s footballing career – and indeed parts of his life – came to be defined by one of the most controversial moments in VFL/AFL history.

His role in what came to be known as ‘The Somerville Incident’ in the 1965 Preliminary Final brought him a kind of footballing infamy that was unusual in those days, and more tellingly led to the premature end of his VFL career. But there was more to Duncan Wright’s story than what happened on that fateful day in 1965.

It was all so different when he joined from Alphington Amateurs in 1960. Wright was born in Finley in NSW but his family moved to Alphington when he was two. He would go on to spend almost his entire life in the inner north-east suburb.

His father had been born and raised in Scotland and knew nothing of Australian football, so young Duncan didn’t actually pick up a footy until he was 14. He started his junior footy with Alphington Park, and by 18 he was starring with Alphington Amateurs, being named in the VAFA combined side that year. The Magpies duly invited him down for the 1960 pre-season.

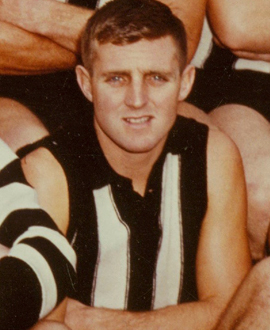

Although only 19 he quickly made a name for himself as a strong, rugged ruck-rover type who was already able to mix it physically with his more senior teammates. That saw him playing in the 3pm practice matches usually reserved for ‘probables v possibles’. The report after one of those games said he had “continually come under notice with good play all over the ground”, while a later game saw him described as “most impressive as a ruck-rover, being outstanding all day.”

Those performances were enough to get him a spot on the senior list, and he spent most of the year getting a solid grounding in the reserves, as well as making his senior debut in Round 12 against Fitzroy.

But then came the first of the controversies that seemed to dog Duncan throughout his career. And it was an unusual one.

His sister Liz, with whom he was very close, was then the captain of the Australian Netball side. One day during the 1960 season she had a game on the same day that Duncan was playing with the reserves. Liz didn’t drive, so Duncan gave her a lift, causing him to be late to the reserves game. Coach Neil Mann didn’t take kindly to the late arrival and left Duncan out of the team.

Duncan was a little miffed – not unreasonably – so he went and played a game for Research in the Panton Hills Football Association, apparently under an assumed name. But their opponents, Healesville, complained and the VFL’s permit committee deregistered him as a result. The Magpies also delisted him, and refused to allow him on the club’s end of season trip to Surfers Paradise.

Having issued that punishment, however, the Pies were ready to forgive Wright and said publicly that they would welcome him back to the club. Even so, it took until 1963 before he would again be seen at Victoria Park.

He played a handful of games that year, but then ran into trouble again in a game at Kardinia Park in which he tangled with Geelong’s famous Lord twins. Both the Lord boys hit the deck, as did Cats skipper Fred Wooller, and Duncan copped an eight-week holiday from the Tribunal.

That suspension delayed his start to the 1964 season, but it still turned out to be his best as he managed 14 senior games. He played mostly off half-back during this time, where his straight-ahead style and take-no-prisoners approach was well-suited. He wasn’t a polished finisher, but that wasn’t what he was there for. The club’s 1965 Yearbook described him in this way: “Duncan is a good ball getter, good mark, mobile, but his play is weakened by poor kicking. Whilst he plays mostly as a defender, he is a good utility player and has performed well as a ruck rover.” The Sun said: "Courageous battler with good hands for marking. Nothing classical about his ground play or kicking but he sticks close and knows how to bump. He is a lively and aggressive 'handyman'."

As it turned out, the 1965 season was a dramatic one.

He played in the first game but suffered several broken ribs and a punctured lung. On his return to the field nine weeks later he suffered a broken collarbone. So it was quite the surprise when the Magpies named him in the team to meet Essendon in the preliminary final. How different things might have been if they hadn’t.

The story is by now well-known. Wright was opposed to a slender half-forward called John Somerville. Early in the game, Somerville was seen lying on the ground 40m behind play with Duncan standing over him, in what has become a famous football photograph. Nobody saw the incident, so there were no reports, but Duncan was subjected to incessant booing for the rest of the game.

The incident was a huge controversy. Victoria Police intervened, interrogating him for 90 minutes, but no charges were laid. The League also opted not to investigate further after receiving conflicting reports from fans claiming to have witnessed it. But the controversy took a large toll on Wright's family. His mother received threatening letters and almost suffered a nervous breakdown.

Wright refused to talk about the incident for many years, but opened up to afl.com.au in 2015, admitting having struck Somerville but claiming he’d been provoked and also saying he’d given the Bomber forward several warnings.

He endured the harsh criticisms that came his way but was still part of Collingwood’s end-of-season trip to Japan. He played all the practice games in ’66 too, and everything seemed to have returned to normal.

But then the club suddenly delisted him, claiming they had too many half-back flankers. Wright suspected the reasons ran deeper.

After his sacking, Wright went to Canberra to work and play football with Acton and get out of Victoria, but soon returned to play local footy. He spent the rest of his life living in Alphington and remained heavily involved with the local footy club. One of those who played against him at local level said that, despite his fearsome onfield reputation, Wright was “one of the nicest blokes you’d ever meet”.

And Duncan Wright’s soft side emerged clearly in that 2015 interview. He held back tears as he told reporter Ben Collins that his biggest regret was having been forced out of Collingwood. "If I had have been allowed to stay (at Collingwood), I would've played a lot more games,” he said. “And I would've loved to have stayed there.”

- Michael Roberts