By: Michael Roberts

Collingwood's debut at Victoria Park – a narrow loss to the established Carlton side – was promising. More than one reporter suggested Collingwood would become an instantly formidable force. Instead, the Magpies finished equal last with Williamstown in their debut season, with just three wins – over Williamstown, St Kilda and Carlton.

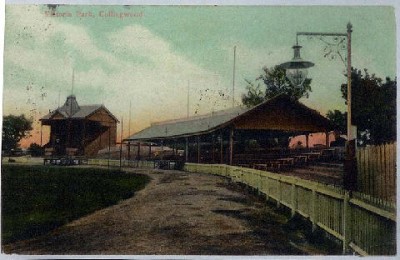

Still, most locals were just happy to have a team bearing the suburb's name playing in the code's elite competition. At least in football terms, Collingwood belonged. And those supporters had more reason for feeling proud of their club when the grandstand that had been promised pre-season was eventually opened for the match against South Melbourne in mid-June.

Observers said they hoped the foundations of the new stand were strong enough, because ‘the stamping of the excited people with which it was crowded was deafening towards the close of the match’. The training room underneath meant the players no longer had to change into their uniforms at the nearby Yarra Hotel in Johnston St, then run to the ground. But the room was small and cramped. Bob Rush, who first used the rooms in 1899, recalled: ‘There wasn't much space in the dressing room and whatever rubbing down you got was while you were standing up.’ The new stand, which stood roughly in the area of the Sherrin Stand before being shifted 17 years later, eventually cost the club almost 700 pounds.

Fans continued to flock to Victoria Park throughout the club's debut season, despite victories being few and far between. Those who couldn't afford the entrance fee of 6d often took to the rooftops of homes neighbouring Victoria Park to watch the action.

The 1890s were tough times. On the field, Collingwood's fortunes improved gradually with each passing year. But the depression deeply affected all the VFA clubs, and Collingwood soon found itself in dire straits: it was more than 1000 pounds in debt (most of which was due on the grandstand repayments), liquidity was a constant problem and attendances and memberships plummeted.

The situation reached a crisis stage until the intervention of the club's newly appointed secretary, E.W. "Bud" Copeland. He arranged loans, introduced new financial disciplines and organised fund-raising initiatives that saved the club from financial ruin, allowing Collingwood to outlive the depression. And Victoria Park was at the centre of Copeland's survival strategy.

The ground had already started to become known as a place for community interaction. In 1892, after a shipwreck took the lives of 15 Mornington footballers, the club staged a gala parade and charity football match. Almost 70 pounds was raised, thanks to the most bizarre football match ever played at Victoria Park, with participants dressed in costumes as druids, clowns, indians, policemen and soldiers.

Copeland saw the opportunity to use Victoria Park to help drag the club out of the financial mire. He organized fund-raising events at the ground, and staged cycling carnivals around the track that ringed the oval in those days. The club also made a concerted effort to promote the ground to women, marketing it as 'a place where men would feel no regret or shame to take their wives, sisters and lady friends’.

Copeland's financial makeover saved the club. His efforts – and the club's coffers – were given a timely, and massive, boost when the team won its first Premiership in 1896. The celebrations afterwards were riotous. Victoria Park and the Collingwood Town Hall were awash with merriment that night, for weeks and even months later.

With an improving financial position and a Premiership under its belt, the Collingwood Football Club not only survived – it prospered. So did Victoria Park. The ground had become more than a little careworn during the 1890s, at least partly because of the Council's reluctance to spend money on maintenance. But that all changed in the late 1890s and early 1900s. The ground was regularly updated and improved: fences were added, floorboards in the grandstand replaced, wooden surfaces were repainted, and the playing arena itself was ploughed, top-dressed and re-sown.

Perhaps the biggest improvement was the addition of a separate ladies pavilion, a basic structure located roughly where the Ryder Stand would later stand. It was built to accommodate the growing band of female fans who followed the club (though, given it appeared a year after a Magpie fan had hit a player with her umbrella, some suggested it was a way to keep some of the more rabid members of the Magpie army away from the general populace!).

With back-to-back flags in 1902-03, the fans kept coming in ever-increasing numbers, and it soon became clear that Victoria Park required a new grandstand. What had been adequate for fans in the pre-VFL world of 1892 was not suitable for the club's football-goers of the early 20th century.

The new grandstand, opened in 1909 on the site of the original 1892 version, was a beautiful building, based on a similar structure a local councilor had seen in Maryborough. This one was built without financial risk to the club, thanks to a 100-pound debenture program that helped fund it, and its opening was the cause of huge local celebrations, including a man being fired from a cannon.

The old 1892 stand was shifted to the south west corner of the ground, where it became a public reserve stand, while the old ladies pavilion reverted to a 'smokers pavilion', allowing men and women season ticket holders to enjoy the new 1500-seat brick grandstand (which stood on the site of the Sherrin Stand). The new stand housed two dressing rooms, committee rooms, a gymnasium and bathrooms and toilets for home and visiting players. It also had a tunnel for the players to use, protecting them from some of the worst excesses of the 'over-enthusiastic' fans. The stand would last until the 1960s.