It's often forgotten that Collingwood's famed Machine team era started with one of the most controversial moments in the club's history – the decision to axe an existing captain.

That moment came just days before the start of the 1927 season, when the Pies sensationally dumped Charlie Tyson as captain, replacing him with Syd Coventry. The move was a masterstroke from the club's point of view, as Syd and his boys went on to create history.

But for Charlie Tyson it was a life-defining moment, not just because it ended his Collingwood career but also because it added significant fuel to the nasty rumours that he had taken a bribe and played 'dead' in the 1926 grand final loss to Melbourne.

Even today, the idea that a Collingwood captain might have 'laid down' in the biggest game of the year defies comprehension: the term 'scandal' wouldn't even do it justice. But back then, there were plenty of people who believed it.

Proponents of the theory pointed to Tyson’s relatively poor performance and a number of questionable positional moves he made as captain during the game. But the prime piece of evidence was his dumping: why would a club drop its captain but for something this serious? When he was seen around town driving a new car, that just confirmed the suspicions.

Tyson, of course, vigorously denied the claims, but the story became part of football folklore anyway. For nearly 60 years it was accepted as the truth. Richard Stremski, author of Kill For Collingwood, was the first to really question the story, and after talking to many of his former teammates, came down on Tyson’s side. He also raised an alternative theory, that some club officials had him 'in the gun' after he'd organised a players' meeting the previous year to air some complaints at the administration.

It's beyond dispute that Tyson did not have a good game in the 1926 decider. But there was evidence his play had been affected by injury and, as Stremski pointed out, the positional changes he made at half-time were not inexplicable, although as things turned out they did not help the team’s cause.

In the end, it was the expectations of Collingwood supporters that helped to set the scene for Tyson’s demise. Collingwood was Premiership favourite from midway through the season; at Victoria Park many believed it was as good as won. That made the eventual failure impossible to swallow. Many supporters were outraged, and the search for scapegoats went into overdrive. In such an environment, the club’s decision to drop Tyson was always going to be interpreted as meaning one thing only.

Tyson wrote to the papers defending himself, and with more than a hint of intrigue said “he could tell a lot more”. This helps support the theory that he believed some officials had turned against him. Stremski, however, concluded that the club had simply decided that the 29-year-old Tyson had outlived his usefulness and should be let go. That it was time to switch to a new leader. But if that was the case then the club’s timing was tragic, because it blighted Tyson's departure and sullied his reputation for decades.

Charlie Tyson was born into a footballing family. His dad, Charlie Snr, was a legend of goldfields football. He played for 18 years with the Kalgoorlie Railways team and spent a couple more with East Fremantle. When he and son Charlie came to Melbourne he astounded everyone by appearing with the Fire Brigade team — while well into his forties!

Despite this heritage of football in the west, young Charlie was actually born in St Arnaud, being taken west little more than 12 months later. He followed in his father’s footsteps in WA, joining Kalgoorlie Railways in 1916 and playing principally as a backman and follower. He made his way to Collingwood in 1920, securing a job at the Metropolitan Fire Brigade.

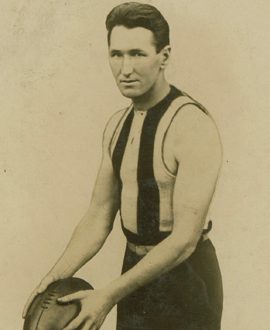

He debuted that first year, playing mainly as a half back and second-string follower in his first appearances in the black and white and soon establishing himself as one of the stalwarts of the team. At just over 183cms (6ft) and weighing in at 82.5kg (13 stone), Tyson had a wonderful footballing physique. He was a strong player, a good overhead mark and a strong, driving kick. He was reasonably agile for his size, being able to turn well, and would battle hard for the ball on the ground. He was not renowned for his aggressive play but did a lot of good, hard work in the ruck where, with “Doc” Seddon, he formed an effective back-up to Les Hughes and Con McCarthy.

With McCarthy and Seddon ending their Collingwood careers in 1921 and Hughes lasting only two games of 1922, a lot of responsibility was thrown on to Tyson's broad shoulders. He responded magnificently and had his best season yet, winning interstate selection. When Harry Curtis stepped down as captain at the end of the 1923 season, the mild-mannered Tyson was chosen by the players to replace him. He was well liked and well respected by the players, as he was by his workmates at the fire brigade. He did not smoke or drink, and was regarded by most of his comrades as straight, honest and strong of character.

After he took on the role, various newspaper reports commented on the extra 'energy' he brought to his game. The Australasian noted, for example: "Tyson, the Collingwood captain, is playing better now than at any period of his football career, and gave a fine display half-back and following; some of his high marking was superb, and followed by a sudden dash and a long, telling kick, his work was very effective." Later that year he was hailed for another "masterly display" after a defensive performance against South Melbourne that was described as "one of his best games since he has been with Collingwood". "Cool and alert in the scrimmages and when on the ball he set a splendid example for his side," said the Age. "His generalship was also of the best."

In his first year as skipper he was a rock in defence, but rarely played in the ruck. The team had a disastrous season, finishing outside the four for the second year in a row— the only time such a fate had befallen Collingwood to that point. Tyson then led the team into two successive grand finals, during which he was regarded as one of the defensive lynchpins of the side.

But he had a naturally placid nature that perhaps wasn't suited to the task of being captain. There were many who felt he was too much of a “gentleman” to provide the kind of inspirational leadership the team needed. It may well have been these concerns, rather than the bribery suspicions, that led to his shock axing.

After he left Victoria Park, Charlie Tyson played three seasons at North Melbourne as captain-coach, and later coached Richmond reserves. But he never really escaped the odium surrounding his dumping in 1927 and spent the rest of his life knowing many people believed he had played dead in a grand final. He deserved better.

- Michael Roberts