What is it that makes a footballer an inspiration to his teammates? There's no one formula, of course, but it's usually a mixture of qualities such as courage, passion, spirit, leadership, will-to-win and desperation. Combine those with copious amounts of talent and you've got the near perfect footballer.

Actually, you've got Bob Rose.

Oddly enough, Bob Rose was never named Collingwood captain. But that didn't stop him being the greatest inspirational force in football during his playing days. He was, of course, probably the best player of his time, and is still regarded among the best two or three footballers the Magpies have ever produced. But his ability to lift his teammates and change the course of games through the sheer force of his will was about much more than talent: this was an almost indefinable extra that lifted an already brilliant footballer into another stratosphere.

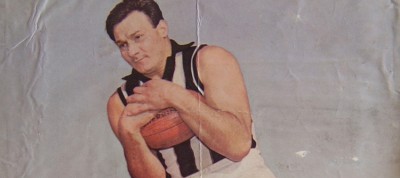

First, the basics. Rose was built a little like a miniature tank and played the same way – albeit a turbo-charged version – whether roving, in the centre or on a flank. He was fast, a superb ball-handler, beautifully balanced, a magnificent long kick and an even better short-passer, slick with handball and great around goals. He was the classic 'see ball, get ball' kind of rover who would throw himself into any situation if the ball was there to be won, strong enough to bust open packs or wrest the ball from opponents and skilled and quick enough to do untold damage with it once he had it.

He was a fierce, almost brutal, competitor who thrived on physical contact and whose shirtfronts left many an opponent reeling. Harry Collier, to whom Rose was often likened, described him as “hard as nails”. “He was never as good as when the going was tough,” Collier said. “He hit them hard, too. Close enough to be fair and sharp enough to hurt plenty.” Essendon’s Jack Clarke once told The Sporting Globe that Rose was "tough, ruthless and nasty”.

Rose possessed seemingly boundless courage and a will-to-win that bordered on fanaticism. Time and again he would lift Collingwood from seemingly hopeless positions. With the Pies down to only 16 fit players in the 1952 preliminary final against Fitzroy, for example, Rose produced a stunning 15-minute frenzy in which he kicked three goals and set up two others for teammates, giving his team just enough of a lead that they could hang on to for the rest of a brutal encounter.

He also had a wonderful ability to nail clutch goals when they were most needed, such as the famous 'goal that sunk the Cats' late in the last quarter of the 1953 Grand Final. That is the most well remembered, but similar high-pressure goals were a regular part of Rose's footballing CV.

It was performances like these which led observers to focus as much on his inspirational qualities as they did on his greatness as a player. Richmond’s Roy Wright said he was the “greatest inspiration any team could have”. TheHerald said Rose “inspires as no man his inches has done for many years”. And Hec de Lacy in The Sporting Globe tagged him “the greatest team-booster in football”.

"He's a bottler, this Bobby Rose," said de Lacy. "He's Collingwood's morale-lifter, frustrator of foreign high hopes, and a man ready and able to fight through skin and skill to establish the Magpie cause. Collingwood have built a tradition on the likes of Rose – team builders, team boosters, steadiers in crisis, men to whom the Australian code spells 'Collingwood' first, foremost and last. Bobby Rose is today's finest team-maker. I've seen him in the ruck. He's dominated the centre for Victoria. He's roved the boots off the best in the land. Terrier-like, he can be the David to the opposition's Goliath any time they want it laid on the line. There are great footballers in this game … but there's none greater than Rose."

Bob Rose was born and raised in Nyah West, on the Murray, and came to be regarded as an outstanding junior footballer (he played senior football at age 11) and boxer. He was a promising young fighter who fought several times at the main boxing stadium in Melbourne. During one of those visits to Melbourne he had a training run with Collingwood (his father and Syd Sherrin were cousins, and Bobby was a passionate Magpie fan). The Pies liked what they saw and signed him after just one session.

He started with Collingwood reserves in 1946, finishing second in the reserves’ best and fairest award, and was rewarded with a senior debut late in the season. He showed little in his first game, not getting his first kick until the third quarter, but kicked three goals in his second game and was on his way.

Rose's game reached its peak in the late 1940s and early 1950s, after a brief return to boxing in the summer of 1948-49 took his strength and fitness to new levels. He won four Copeland Trophies in five seasons, and finished runner-up in the 1953 Brownlow Medal. He was also named all-Australian that year. His teammates loved him. Thorold Merrett said he epitomized all that was good about Collingwood, and “gave everything until the last drop of blood”. By this time Rose's status in the game had elevated to the point where many described him as the best player in the game, Collingwood's best-ever and one of the best footballers of all time.

But just a couple of years later, aged 27, he stunned the football world by walking away from it all. His body was pretty banged up from the pounding he had subjected it to through his 'human battering ram' style of play, but he had plenty of good football left. Unfortunately he was offered a lucrative coaching and employment offer at Wangaratta which Collingwood wouldn't match, or even get close to, so Bob decided to move to the country and set up his family.

After seven years with Wangaratta Rovers (where he was so loved that he became known simply as 'King Bobby'), he returned to a hero's welcome at Victoria Park as coach for the 1964 season. The Pies had finished seventh in 1962 and eighth in a horrid 1963 season marked by infighting and a board upheaval. But Rose took essentially the same list all the way to a Grand Final in his first season as coach, and went within two minutes of winning a flag.

Just as importantly as the on-field success, Rose re-unified the entire club after the traumas of 1963. There was a real buzz around Victoria Park in the 1960s: Rose put together a team that played scintillating, free-flowing football, the newly opened Social Club building was a hive of activity, and two new grandstands went up. The only thing missing was a Premiership, and Rose's ill-fortune in that regard – especially in 1970 – has passed into football folklore.

So, too, has the way he handled those crushing defeats, and the misfortune that hit his family in 1974 when son Robert, himself a VFL footballer and Victorian cricketer, was left a quadriplegic after a car crash. The quiet dignity and determination Bob showed in those dark moments – and as he continued to look after Robert in the years that followed, during which he returned to Victoria Park as a board member and briefly for a second coaching stint – won him even greater respect and admiration not only at Collingwood but throughout the football world.

That respect was never more evident than in the wake of his death in 2003. Rarely has the football world seen such an outpouring of emotion for one man. He had been inducted to the AFL Hall of Fame in 1996, named in the centre in Collingwood's Team of the Century and named by one newspaper in 2009 as one of the 25 greatest players never to win a Brownlow. He remains the most revered name in Magpie history and was the first player to be immortalized with a statue at Collingwood's HQ in Olympic Park.

That statue bears an inscription that stands as perhaps the finest tribute to Bob Rose's influence, one that shows he never lost his capacity to inspire Collingwood footballers – even after his death. A young boy once told Rose that whenever he played football he wrote a message on his hand. It is that message that now sits beneath Rose's statue, and which became an unofficial motto for Mick Malthouse's players during their 2003 campaign that took them to a Grand Final. It reads: "Play tough, play brave, play like Bobby Rose."

- Michael Roberts